Assistant Editor Madeleine Wattenberg: The use of disability as a plot device or poetic metaphor is less of a trend than a long-lingering literary tradition. Such moves are lazy at best and harmful at worst, yet we consistently receive submissions in our queue that draw on these old tropes. Some stories feature some version of a narrator learning to value their own life through an interaction with a disabled neighbor: “We’re all broken,” the narrator might muse whilst ascending the stairs back to their apartment. Similarly, few weeks go by where we don’t read a poem or two featuring blind or mute skies. Or maybe the pain of losing a lover is compared to a missing limb.

To think more about why these tropes and metaphors are problematic, I turned to Emily Rose Cole, previous CR editorial assistant and current PhD candidate in English and Disability Studies at University of Cincinnati:

First, can you talk a little bit about ableist language generally? What does it mean for language to be “ableist” and what are some common phrases in everyday conversation that go unexamined?

In a general sense, ableist language is language that assumes the nondisabled body by default and/or actively discriminates against disabled bodies, including physical disabilities, mental illnesses, or chronic illnesses. There are certainly more specific terms used in disability-focused circles (saneism, for example, specifically describes oppression against folks with mental illnesses), but ableism is a general, go-to term to flag actions or language that’s discriminatory toward disabled folks. Once you start looking for it, ableist language is everywhere, to the point where it’s difficult to escape.

One of the most common examples found in literary circles is the idea that editors of a literary magazine or contest “read submissions blind,” which means “we read our submissions anonymously.” [Note: The Cincinnati Review used this language in past contest submission guidelines but recently switched to “anonymous” based on this interview!] Though it sounds innocuous, this phrasing evokes blindness as a metaphor to signify lack of understanding. Similar metaphorization occurs when writers use terms like “love-blind,” “blind spot,” “fell on deaf ears,” etc. Even common insults that many people consider mild, such as “dumb,” “lame,” “idiot,” and “imbecile,” have deeply ableist roots.

Poetry has a pretty extended tradition of using disability-as-metaphor. What are the most frequent examples that you encounter? Can you talk a little bit about why it’s problematic to use disability merely as metaphor?

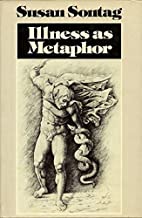

It’s hard for me not to spend five paragraphs yelling about Susan Sontag’s groundbreaking essay Illness as Metaphor in answer to this question, so I will limit my yelling to a brief quote that essentially summarizes Sontag’s thesis: “My point,” she writes in her introduction, “is that illness is not metaphor, and that the most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”

Sontag is being a little hyperbolic here—it’s not possible for anyone using language to completely purify themselves of metaphoric thinking, since metaphors are baked into so much our language wholesale. (Observe: “baked into” is in itself a metaphor, though it is not ableist so much as delicious.)

However, Sontag and many brilliant disability scholars who follow her have done a lot in the past couple of decades to uncover the harmful ways in which disability and illness are often metaphorized as, or in the context of, something bad or scary: student debt is “crippling,” that racist meme is “infectious” and spreads “like a plague,” ignorance is “a cancer” and on and on. When we talk about disability in terms of metaphor, we set up the experience of having a disability or chronic illness a horrible, life-ruining thing.

Which it’s not! I have multiple sclerosis and I’m happy and fine! And, as it turns out, so are lots and lots of people with disabilities and chronic illnesses the world over. Yes, disability is inconvenient and expensive and absolutely does have the potential to permanently damage someone’s quality of life. But this is not the fault of the disability, so much as the fault of a highly individualized society that is built for nondisabled people and, at least in America, provides a very thin, nearly nonexistent social safety net. Thinking of disability in terms of harmful metaphors does everyone a disservice, because it encourages us to view our bodies as “broken” if they don’t fit the mold of what is “normal.”

The best advice for nondisabled writers wanting to write about disabled characters often seems to be Don’t. There’s also an understandable frustration with writers who decide it’s easier to imagine a world without disabled people rather than grappling with what it would mean to create, both inside and outside of fiction, an accessible world where disabled people survive and thrive. Is there a way to reconcile these two positions?

I think it’s possible, but that such a reconciliation requires a lot of inward, individual work that requires questioning one’s own biases and personal priorities. Because that kind of work can only be done on an individual level, it’s more or less impossible to offer good blanket advice that will apply to every single writer.

The history here is complex; generally, the common wisdom in situations regarding minority groups is that “more representation = good,” because most minorities (whether they’re folks of color, queer folks, etc.) just don’t show up in stories much at all.

The difference with disability representation is that disabled folks have been appearing in literature and film for centuries; it’s just that their role in a story tends to be a vehicle for an able-bodied character’s revelation (“Cathedral” is a good example of this) or as an object lesson in pity (think Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol).

Alternately, these characters exist in the story to fulfill a disability-based archetype, such as a blind mystic or seer (e.g. Greek mythology’s Tiresias) or disability as superpower (aka the “supercrip” myth, e.g. Rain Man, Daredevil). Very rarely are disabled characters allowed to exist in a story as three-dimensional characters with their own motivations and desires and role in the story outside their disability.

I think it’s possible for a very thoughtful and empathetic writer to write three-dimensional disabled characters, but I don’t blame anyone in the disability community for being skeptical of nondisabled writers’ motives. If you really want to write a disabled character, I recommend first thinking about why you want that character to be disabled. Does their personality go beyond being a disabled person? Does their disability only limit them when it’s convenient to you/the story? Do you actually know anything about the lived experience of having that disability? Are you willing to employ sensitivity readers and listen to what they say? These are all questions to ask first.

Are there other ways that literature is inaccessible?

Absolutely. The literary community has a long way to go in terms of making its events, residencies, and conferences more accessible. Most coordinators of reading series, conferences etc. don’t think about the accessibility needs of disabled folks, like handing our access copies, employing CART [Communication Access Realtime Translation] technology, or even, bare minimum, holding the event in a wheelchair-accessible location. This isn’t true for everyone, but more often than not, accessibility for these sorts of events is a tacked-on afterthought, rather than a serious consideration that organizers make from the beginning.

Even at big literary events like AWP, many presenters don’t bring access copies of their panels or read access statements at the beginning of their presentations. It’s actually such a pervasive problem that I proposed a panel at AWP this year that’s designed to help folks outside the disability community understand how to center access when planning events.

What resources would you recommend (online or in book form!) for writers wanting to learn more? Who are a few of your favorite contemporary disabled writers?

So many! The first place to start, I think, would be Alice Wong’s brilliant Disability Visibility Project and Vilissa Thompson’s Ramp Your Voice, both of which feature a ton of articles, resources, interviews etc. about disability studies. The New York Times recently put out an anthology called About Us featuring essays from its Disability Series, and I also highly recommend the new Unsung Masters anthology about Laura Hershey, the Beauty is a Verb Anthology, the QDA: A Queer Disability Anthology and the disability-focused literary journals Wordgathering, Rogue Agent, and Deaf Poets Society.

As for my favorite disabled writers, I’m only going to be able to offer a partial list, since I have so many. But a few of my favorites include Jillian Weise (whose new poetry collection Cyborg Detective is out now!), Harriet A. Washington, Keah Brown, Eli Clare, Meg Day, Elsa Sjunneson-Henry, Ilya Kaminsky, and Eula Biss.

Emily Rose Cole is the author of Love & a Loaded Gun, a chapbook of persona poems in the voices of mythological and historical women, published in 2017 Minerva Rising Press. She has received awards from Jabberwock Review, Philadelphia Stories, The Orison Anthology, and the Academy of American Poets. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in American Life in Poetry, Best New Poets 2018, Carve, and River Styx, among others. She holds an MFA from Southern Illinois University Carbondale and is a PhD candidate in Poetry and Disability Studies at the University of Cincinnati, where she is a Taft Fellow. Her website is www.emilyrosecolepoetry.com.