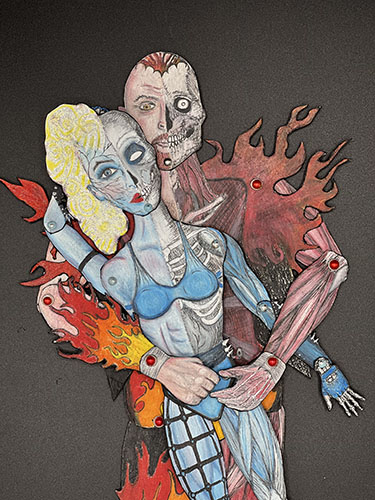

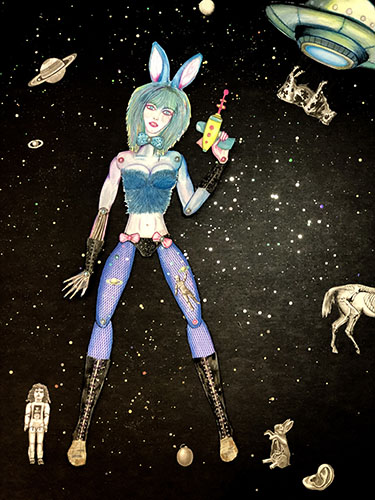

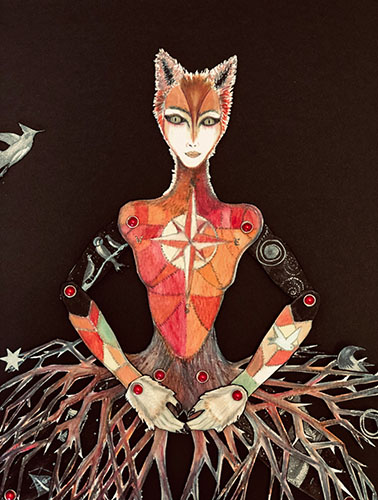

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: As someone who writes and talks publicly about dolls, their history, and especially those who make them, I was delighted to learn that L.I. Henley, winner of the 2022 Robert and Adele Schiff award for her essay “On the Subject of Bearing and ‘Other Options,'” is a doll-maker, herself. Henley’s paper dolls—or, rather, dolls made out of paper—are fantastical, colorful, fully jointed and able to pose in a variety of positions. They do not aim to please (in fact, some of them are downright intimidating) but they are pleasing objects, forbidding and alluring, in turn. In the following interview, Henley describes her doll-making process and invites us to see the dolls in our favorite poems—and the poem in every doll.

BW: Tell us a little about your history with paper dolls. How did you begin making them, and when, exactly, did paper dolls start to intersect with your literary interests?

I have to start by talking about my history with paper. As an only child of divorced parents who worked full-time I spent many hours waiting in places where I had to be quiet and self-sufficient. I guess my parents didn’t think to bring toys, because I remember being empty-handed in dull rooms fairly often. But there was always paper or a way to find paper. Fold it, crease it, maybe add some spit in lieu of glue, and you’ve got a little house. I was a story maker from the beginning. Inside my head I could narrate a story about my paper house, dance the characters through the rooms, imbue the set with drama. All anyone would see, if they bothered to look, was a kid staring at a flimsy structure made of notebook paper.

From a young age I painted and drew faces, bodies, people. I stopped making art between the ages of twenty-six and thirty-six due to illness. At the start of the pandemic I made erasure poems and collages from my grandmother’s copy of On Entertaining by Emily Post, and that was my reintroduction to visual art. I have a lot I could say about the connection between my illness, the pandemic, working with paper, and the impulse to make dolls, but I’ll save that for another time.

I’d like to think my doll-making ability had been brewing since childhood because I made at least fifteen unique dolls, over ninety reproductions of three of the originals, and several animations within three years while also writing and managing pain.

BW: Did you/do you have a favorite paper doll or paper doll illustrator? If so, what do you love about them?

Tom Tierney is classic and also a favorite. His renderings of the 1920s-and-30s fashions of Russian-born designer Erté are so cool. My mother collects art- deco prints and embroideries, and even as a kid I appreciated the lines, colors, and textures of the clothes and the androgyny of the models. The other kind of art I was exposed to (again, by my mother) was that of fantasy: fairies, goblins, elves, forest creatures.

Arthur Rackham, Warwick Goble, and my absolute favorite, Brian Froud, were all early influences in regard to my illustrations. Somehow I think I have unconsciously combined fantasy and art- deco design to make the dolls (I mean, I use a lot of gold!). There aren’t any Froud paper dolls around that I know of, though that would be so awesome. If you look at the bodies of my dolls, you’ll see long legs, thicker thighs, elongated waists, long necks, and usually flatter chests: pretty similar to both the art- deco fashion models and many of Froud’s forest creatures. There are some wonderful articulated paper doll artists on Etsy. Sandra Arteaga is a favorite. I believe hers are digitally created.

BW: Paper doll enthusiasts have their own preferences about exactly how “poseable” they want their dolls to be. Some paper dolls, the fashion dolls that one cuts out of a book, are usually a single piece with no possibility of movement. Your work is more “dolls made out of paper” than the classic paper doll with a trousseau of tabbed garments. Why do you choose to make dolls that are poseable and decidedly more involved to craft?

Yes, dolls made out of paper. The clothes and skin of my dolls are one and the same, which is why each limb is so ornately crafted, layered with textures and various mediums. I sometimes spend forever building up layers and then carving hairs or veins or feathers. I love your question about choosing to make the dolls poseable. To make art that is not static, that can change even once it’s been made, means there is no being done with the thing; the life of the art piece extends beyond my handling of it. Photos, paintings, sculpture: all are fixed, and the only thing that changes, perhaps, is interpretation.

But poseable figures, especially ones with lots of joints, can change in shape, composition and mood. Even if a doll’s face is frozen in a smile, the implication of that smile changes when the legs are squat in a birthing position and the arms are reaching to the sky. Tilt the head a bit, and the smile is mischievous or coy. People who have purchased my dolls love taking photos of them in various poses and locations. They get to play and also collaborate in the artistic process.

BW: You’ve made a series of astonishing paper dolls in response to the work of fellow poets. What was that like? Did you get input from the poets at all? Were they particular about their dolls? Or were they happy just to see their work “dolled up”?

Paper Dolls & Books is an ongoing series that involves first finding books that feel right for the project. How do I know when a book is right for PD&B? I have to love it enough to read it many times. Strangeness goes far with me: mystery, lyricism, a strong sense of either the narrator and/or the world that’s been built. But it goes beyond love. The subject matter has to be right. Meaning, if the book is quite serious in subject it may not be appropriate for me to make a doll for it. Predominantly I’ve included poetry books, but most recently I made a paper doll scene (not sure how else to describe it) based on an essay in Sue William Silverman’s collection How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences.

Input comes to me from the book, which I read many times and keep near me, revisiting certain pages repeatedly while I’m working. I try to really listen to the book, to spend time getting to know it like I would a friend. And in a friendship, or any relationship, two people form a third space. The doll is the third space. It’s the book plus me equaling something new and yet familiar. I’m not sure I could personally achieve that kind of intimacy, that kind of alchemy, by writing a standard review.

“[The doll] felt so true, so familiar. Like she held all the little keys to the years-long life of the book in every part of her. Like she was made OF the book. I kept finding tiny new wondrous details, spiders and constellations and spoons and feathers written on her, tucked under her thicket-skirt–—so much like the way we carry certain motifs through years of writing that serve as portals back inside the psyche of a book. That she was so lovingly curated, and my book, so witnessed and lived-with to produce such a piece of art, and that this response was a slow labor of responding.”

Jennifer K Sweeney, author of Foxlogic, Fireweed

As poet Jennifer Sweeney says about my dolls, the doll making is “a slow labor of responding.” I just love that. Time is probably the most precious resource for anyone in the arts. In our community of writers the most generous thing we can do for each other is to give our time. Conversely, I give to myself when I dedicate time to the slow labor of rereading, planning, cutting, forming, carving, photographing, posing.

Though I do not ask for input from the authors themselves, I do always contact the writers first explain the project, show sample work, and build a rapport. I am essentially asking for permission to engage with their words privately and publicly. Trust and transparency are key. I send process photos every couple of weeks while constructing the dolls, which the writers seem to appreciate. It’s a mutual “cheering on” of the other.

BW: In writing about your “Paper Dolls & Books” project, you quote the adage that “the best response to a poem is a poem.” How is a paper doll a poem?

I’m not sure a paper doll is a poem any more than anything else is. But what I love is the idea of art being a chain reaction, that the life of the poem or story or the photograph or the sculpture can go beyond reception. I don’t think people create in a vacuum. We are all inspired by the work around us. I am the poet, essayist, and visual artist I am because of the work I’ve been exposed to (plus, okay, my “unique” imagination, but I’m pretty sure my imagination was formed by fantasy films of the ’ 80s and 90s, The Talking Heads, and my parents’ paperback novels). I think the best Art (I’m talking about all the arts here, not just written, or visual) makes people want to make more art.

BW: You also make animations using your dolls. What’s your process with that? Do you think that the animations help you get to know the dolls better, or does your knowledge of the dolls-as-characters influence how you make the animations?

The process is a little different depending on the initial goal. I made a short film with one of my best pals, oil painter Zara Kand (“What She Found in the Cave”), and that started with us storyboarding a short scene. Zara makes incredible hand-painted stop animation (such a rare talent, and talk about a time-intensive pursuit!), and we knew she’d animate the set and I’d create the dolls. We started with Zara’s still semi-wet cave painting and my Cave Girl and Monster Girl dolls. To film the movie we worked together side by side in my studio, me moving the dolls and Zara changing the light, shadow, and water as we went. Of course, we had to take a picture of each new, tiny movement. It was tricky! My husband, Jonathan Maule, did the sound and editing for us.

Other times I start with the doll. After the first few dolls I started making them with as many joints as I could, which makes for more expressive movement. I made a blue furry monster-goddess with thick, long goat legs, and I got the sense that she needed to dance and transform into a multi-headed, multi-legged beast. At the end of the video her tongue pops out and her eyes flash red. It wasn’t until I started animating her that I realized her body could contain multitudes. This is what dance and other forms of ecstatic movement do for us, right? Unleash our many, hidden selves? (Oh, if there is anyone out there doing interpretive dance of poems and prose, I’d love to see that!)

“It was so cool to see [L.I. Henley’s] process of trying to create art that is faithful to the spirit of The Dead Wrestler Elegies, as she found an intersection between beauty and ghastly violence. When I look at her work it’s almost like that doll is a missing poem from the book!”

Todd Kaneko, author of The Dead Wrestler Elegies

BW: Any future doll-plans? Doll-ambitions? Dolls in the works?

I’m finishing a collection of essays right now, but once that’s done I plan to get back to my PD&B series. I’m looking at Jericho Parms’s essay collection Lost Wax. I taught her essay “A Chapter on Red” in a recent workshop and just love it, plus the speaker of that essay loves paper. It seems like a good match. In addition to PD&B, I want to make more spider dolls. They are a ton of work since each leg is articulated twice and the head also moves. But they are incredibly fun to animate.

I’d also love to animate a scene from my novella in verse, Whole Night Through, which takes place in the Mojave Desert where I grew up. I also hope to do more interviews about the dolls and my series because I could talk about books, dolls, and paper until I pass out.

L.I. Henley was born and raised in the Mojave Desert of California. An interdisciplinary artist and writer, she is the author of six books including Starshine Road (Perugia Press Prize) and the novella-in-verse Whole Night Through. Her art, poetry, and prose have appeared most recently in The Adroit Journal, Brevity, The Indianapolis Review, The Southeast Review, Southern Humanities Review, The Cincinnati Review, and The Los Angeles Review. Her personal essays on pain, illness, and the Mojave Desert have received national recognition including the Arts & Letters/Susan Atefat Prize and the Robert and Adele Schiff Award. She is the creator of Paper Dolls & Books, a series of jointed paper dolls inspired by her favorite books. She also teaches online creative nonfiction workshops. Find her at www.lihenley.com and on Instagram @lihenleyart.