In our spring issue, Toronto resident Joylyn Chai’s essay “Not Wanted in the Garden” explores complicated themes of colonialism, family relationships, and gardening. We’re honored to host her reflection on the Toronto Land Acknowledgment and how it relates to that essay.

Joylyn Chai: I have lived most of my life without a daily ritual except those that have been imposed upon me. As a little girl, I sang “O Canada” every morning at school. After, we were asked to solemnly bow our heads for the Lord’s Prayer. Then we performed light stretches and jumping jacks to the tune of “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.” So inspired by the song, I once procured a tattered piece of yellow fabric to fasten around the young maple in front of our house. Not knowing the meaning behind the lyrics, I didn’t realize I might be encouraging a weary veteran to rekindle an old flame.

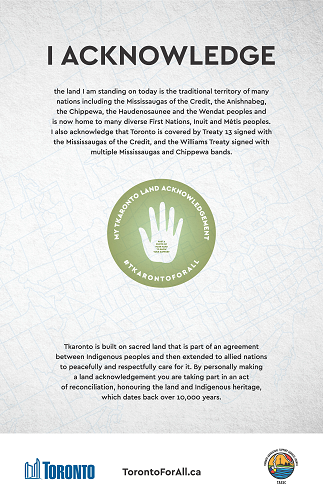

Morning rituals at schools in Toronto have changed since I was a child. As of more recently, the Toronto Land Acknowledgment is recited:

We acknowledge the land we are on is the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13 with the Mississaugas of the Credit.

Tkaronto is built on sacred land that is part of an agreement between Indigenous Peoples and then extended to allied nations to peacefully and respectfully care for it.

By personally making a land acknowledgement, you are taking part in an act of reconciliation, honouring the land and Indigenous heritage which dates back over 10,000 years.

Since its introduction in 2014, I have heard the Land Acknowledgement in schools, libraries, restaurants, stores, parks, backyards, and on Zoom calls. But for the longest time, I didn’t think it was my responsibility to participate in reconciliation. The sins of the colonialist father are not the sins of the immigrant-settler. Dr. Susan Dion, a Potawatomi-Lenapé scholar and professor at York University, refers to this attitude as the “perfect stranger.” How could I possibly have a relationship to Indigenous peoples and Canada’s colonialist past? None of that had anything to do with me. Then I started gardening.

In my essay “Not Wanted in the Garden,” I describe how I tend to my garden and make a connection to its maintenance with colonialism: “encouraging what is wanted and eradicating what is not.” This includes weeding all sorts of beautiful plants I don’t even know the names of. There are ones with tiny waxy leaves in the shape of double sweethearts. Others are a perfect playing-card spade at the end of a supple ivory stem.

One overcast morning, as I was tearing out whatever I didn’t want, I thought of the Land Acknowledgement, and like lightning, another thought landed in the middle of my mind like a thrown rock: Who gave you the right to decide what lives and what dies? Claiming ownership comes with arbitrary and disproportionate power. I was overcome with shame.

The Toronto Land Acknowledgement asks us to “peacefully and respectfully care” and “honour the land.” I started worrying that gardening does not honour the land at all. Perhaps what “I am creating, mostly through the process of ruthless elimination,” perpetuates my colonialist attitudes.

How could I reconcile the Land Acknowledgement and my obsession to arrange nature in the most contrived and unnatural ways? The rock in my mind continued to rattle until I read about the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s seminal book Braiding Sweetgrass (Milkweed, 2015).

It never before occurred to me to thank nature, not just for the pleasure it provides me but for the ways in which it thrives and is necessary for my own survival. When I first read the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address, I was awestruck by its beauty and humility. It is a comprehensive recitation of gratitude that doesn’t want anyone or anything to be excluded:

We have now arrived at the place where we end our words. Of all the things we have named, it is not our intention to leave anything out. If something was forgotten, we leave it to each individual to sent such greetings and thanks in their own way. And now our minds are one.

This year, for the first time in my life, I now have a daily personal ritual. Every morning as the sun is rising, I walk out into my garden to thank the rocks, the plants, the sun, the soil, the trees, the birds, the air—and the weeds. I hope this is the first small step I can make to honour the land and its Indigenous heritage.

Joylyn Chai is Chinese-Jamaican Canadian and teaches English to newcomers in Toronto. Her work has appeared in Thin Air Magazine, This Magazine, The Fiddlehead, The Smart Set, and other publications. Her essay “Gridiron and the High Seas,” published in The Under Review, has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.