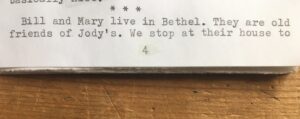

Our Issue 17.2 is finally arriving in contributor and subscriber mailboxes after a delay due to the postal service’s unprecedented holiday demands. If you haven’t gotten your copy yet, it should be on the way!

With each new issue, we invite contributors to say something on the blog about their piece in the journal or to broaden the conversation around it. This week, we hear from Kailyn McCord about how her essay “The Old Man at the Edge of the World” (read an excerpt here) began, and how her reflection on that experience helped her think about crafting subjects in nonfiction.

Kailyn McCord: When I read nonfiction, I find myself expanding the character of the writer into a whole personhood, a complete being constructed primarily of my imagination. Most recently, I did this to Ann Patchett. After I read These Precious Days, she blossomed in my mind: discerning, self-analytical, delicate, Southern, a little brave. Ann Patchett was not this way sometimes, but all the time. I was certain of it.

Beyond leaving little room for the difficulty of human imperfection, this habit of equating a finished piece of writing with the Platonic ideal of its author also obscures any examination of the relationship a writer has to their subject. For me, this relationship is anything but ideal. It is always quite real, and often messy, and takes a lot of time to understand.

I started writing about Mary and the old man the day I met them. This was eight years ago, and my very first day in Alaska. I’d decided to make a zine, which I typed on a typewriter and distributed via snail mail, and over the months, Mary and the old man appeared again and again. The series began with a portrait of their dog yard (“The Dogs, Part 1”), and ended with “How I Learn to Cut A Fish,” a short meditation on processing. The couple appeared in photographs, contributed recipes to the zine’s food issue. As they were a significant part of my life that year, so they were a significant part of my writing.

The draw to subject, for me, is a drive that is impossible to ignore, but one whose source is mysterious, sometimes infinitely so. I am drawn to write about Mary and the old man, and have been for some time, but the exact why behind that draw—what drives the writing to swirl around the question of them, again and again—what is that? Surely, it is not the same now as it was eight years ago.

Over the years I worked on those zines, I was on the verge, the future brimming with newness, questions, travel. Then, I saw Mary and the old man as the ultimate adventurers, having left their childhoods in the lower forty-eight and found each other in Alaska, their life some miraculous result of courage and recklessness and luck. Five years later, during the first draft of “The Old Man,” I was in a much different place. The idea of settling down was no longer the bridle I’d feared but its own great possibility, and one I desperately wanted. Mary and the old man had become the other side of their own coin, no longer beacons of a great leap, but examples of commitment, rooting, a steadfast companionship no matter what the adventure.

Mary and the old man are too old to have done much changing in such a short span. The change, of course, was me.

Perhaps I am not saying anything different than what nonfiction writers of a particular ilk have said for a long time, which is that ultimately, every subject is you, and the drive to understand yourself on the page is what propels the work forward. But perhaps I am also saying that subjects—the ones that haunt us, the ones that seem to demand a return, over and over—are asking something similar, perhaps, as the drafts we craft around them: time to expand, time away, space to metamorphose into whatever next thing they (we) will be. And like the essays banished to languish forever unedited in the drawer, sometimes the iterations of subjects in a particular draft are only stepping stones on the way to their better selves.

I do not think I would have come to the present iteration of the Mary and the old man had I not spent significant time with them in their previous iteration first. It’s not that the writing in the zines was bad (although it was), but rather that, as surely as Ann Patchett is not who I concoct her to be (sorry, Ann), so Mary and the old man are built of an invisible scaffolding that extends far beyond what you see of them as subjects in a finished piece. Before they became what they are to me now, they necessarily had to be something else, and while that something else is invisible, it is not optional. That time and that writing wasn’t wasted time, not at all. As Mary would say, it was time for becoming.

Kailyn McCord lives in Oakland, California. Her work has appeared in Ploughshares, Brevity, Lit Hub, and Alta magazine, among others. With support from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Ucross Foundation, and the Mendocino Coast Writers’ Conference, Kailyn is currently working on new fiction about the metaphysics of disaster.

(To read more great literary nonfiction from Issue 17.2, you can buy copies of the issue in our online store, including the digital version, which is just $5.)