Episode 2: Astrology (Pisces)

In “What You Should Know to Be a Poet,” Gary Snyder lists what he feels to be some indispensable resources and skills for poets, including:

your own six senses, with a watchful elegant mind.

at least one kind of traditional magic:

divination, astrology, the book of changes, the tarot;

dreams.

As I am knowledgeable about astrology, its inclusion drew my attention—especially as it can be a touchy subject. Reactions range from “What, you believe in Santa Claus too?” to “You may know my sign, but you don’t know me!” Both statements are true (word to K. Kringle). Still, I can’t help having grown up in a Mexican-American household, which, for me, meant having several depictions of the Last Supper around the house (painting, mirror, clock, etc.), as well as saint candles and rosaries by bedsides. It also meant enacting several rituals to combat the Evil Eye (¡Ojo!), one including an egg.

Most relevantly, though, it meant this man:

This is Walter Mercado, a television personality and astrologer. Whether on TV or on the radio, Mercado’s horoscopes for day to day life were a definite presence and influence in my formative years. (Speaking of, the word influence has an older use specifically tied to astrology, i.e., the influence of the stars, because of how the stars, uhm, influence one’s life.)

Fast forward to my reading Snyder’s poem . . . and to pondering what poetry has to do with astrology. As a poet, I work hard to stay away from generalizations and clichés. What is of interest always is specificity and possibility. Once I read past the generic horoscopes in the newspaper and learned about my chart, I began to form a specific narrative lens with which to view my life. Astrology as theoretical lens, if you will. In my reading, I have learned that each sign has an essence that plays out in poets’ work in various ways.

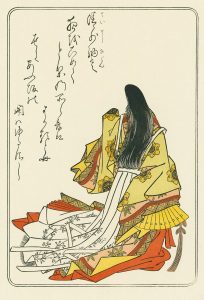

Here, I am focusing on Pisces and my experience reading The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon.

Here, I am focusing on Pisces and my experience reading The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon.

A few weeks ago, I traveled to Warrensburg, Missouri, to participate in the Creative Writing and Innovative Pedagogies (CWIPs) conference. Along for the ride was Sei Shonagon’s book, which is filled with lists, musings, and observations of 11th Century Heian Japan. A seemingly impersonal project, Sei’s book becomes personal indirectly via the power and focus of her writing.

At one point in my travels, I had the following text message exchange with my wife (excerpts from Shonagon were shared via photos):

me: Also, been reading Sei Shonagon, thinking of her as a Pisces.

wife: I can see that.

me: Case in point:

84. I Remember a Clear Morning

I remember a clear morning in the Ninth Month when it had been raining all night. Despite the bright sun, dew was still dripping from the chrysanthemums in the garden. On the bamboo fences and criss-cross hedges I saw tatters of spider webs; and where the threads were broken the raindrops hung on them like strings of white pearls. I was greatly moved and delighted.

As it became sunnier, the dew gradually vanished from the clover and the other plants where it had lain so heavily; the branches began to stir, then suddenly sprang up of their own accord. Later I described to people how beautiful it all was. What most impressed me was that they were not at all impressed.

wife: Nice.

me: Also:

61. One of Her Majesty’s Wet-Nurses

One of Her Majesty’s wet-nurses who held the Fifth Rank left today for the province of Hyuga. Among the fans given her by the Empress as a parting gift was one with a painting of a travelers’ lodging, not unlike the Captain of Ide’s residence. On the other side was a picture of the capital in a heavy rainstorm with someone gazing at the scene. In her own hand the Empress had written the following sentence as if it were an ordinary piece of prose: When you have gone away and face the sun that shines so crimson in the East, be mindful of the friends you left behind, who in this city gaze upon the endless rains. It was a very moving message, and I realized that I myself could not possibly leave such a mistress and go away to some distant place.

wife: Haha. I love it. “That they were not at all impressed.” That could be the entire story of my childhood.

me: The translator comments on her snarkiness essentially, and describes her admiration of Her Majesty as bordering on pathological.

wife: Haha.

me: Has to be Pisces because another famous translator describes her as the greatest poet of her time, a fact “evident everywhere in her prose” but not her poems. Think about it: it’s both the best and worst compliment at the same time. . . .

A few things to note: my wife is a Pisces (I myself am a Virgo; see how neatly all over the place I am). Also, Shonagon’s birthdate is not known. In identifying her as a Pisces, I am going on intuition and the lens I spoke of earlier. My favorite Pisces poets convey in their work a sense of being forgotten, dismissed, and misunderstood, as well as being generally okay with that. Kind of.

In his poem “The More Loving One,” W. H. Auden expresses what I feel to be an essential Pisces sentiment. From the “go to hell” and comments on indifference at the start, to imagining “an empty sky” at the end, Auden’s meditation on the stars presents the complicated nature of being human, of being able to relate only in human terms. His poem is kindred to what Shonagon means when she writes: “What most impressed me was that they were not at all impressed.”

The More Loving One – W. H. Auden

Looking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.

How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.

Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total dark sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.