Assistant Editor Toni Judnitch: Anyone who knows me knows that I am obsessed with first-person narrators. In my own fiction, I love working with the obstacles presented by close-lipped characters and speakers who manipulate language to simultaneously (and paradoxically) reveal and obscure their pasts. I aim to create moments that show slippages, cracks, moments where the speaker says more than she intends.

The beauty of first-person narration lies in its complexity. While beginning writers often choose this point of view to feel a greater sense of connection to their characters, the form’s true potential is much more expansive. The fallibility and haziness of memory, the way in which (and the speed at which) the narrator deploys information, and their level of reliability complicates the perspective in a truly exciting way. Understanding these techniques will help writers at any stage create richer, more intricate narratives.

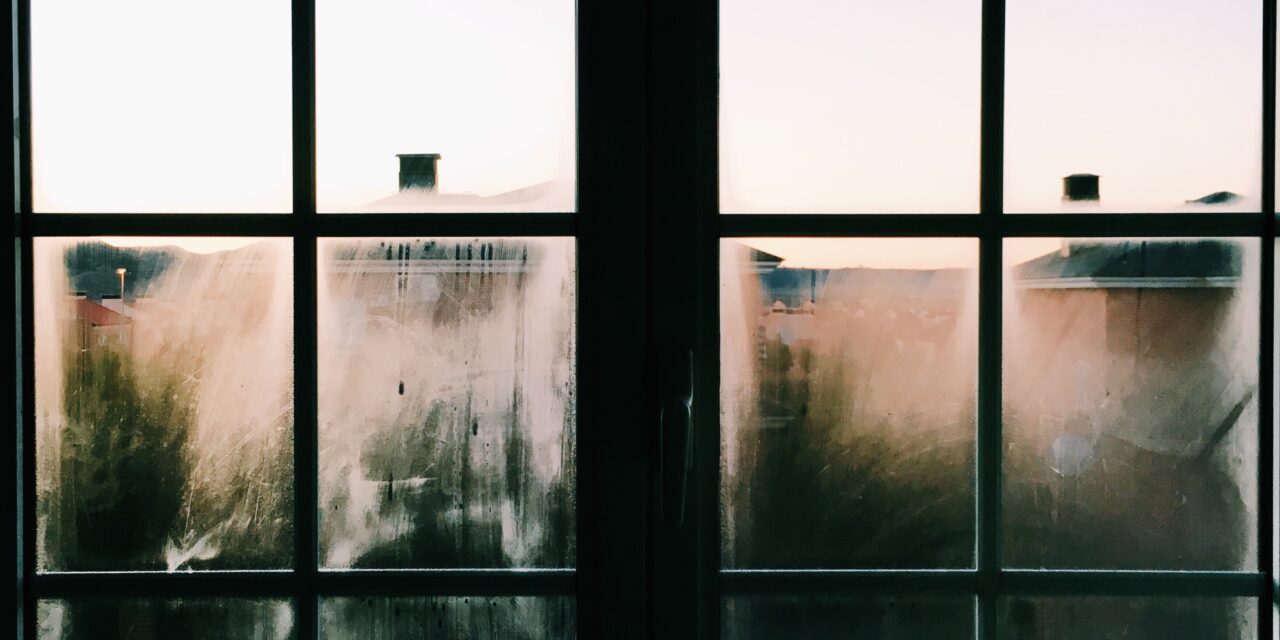

It’s helpful here to turn to Cris Mazza, whose essay “Too Much of Moi,” sets out detailed guidelines for first-person narration. She writes, “Really effective first person should be like viewing the story’s events through a clouded, scratched, nicked, warped or otherwise marred pane of glass, or even plastic.” On one level, readers can follow the events of the story, but we have to remember that the first-person narrator is often telling the story from a distance. Because the narrator “I” is distinct from the character “I,” there is an inherent tension between the facts of the story and the telling of the story overall.

A thought exercise: A girl’s brother drowns when he is a child. She’s not much older than him when the event occurs. Her child-self telling this story a week later will be markedly different from how she would tell the same story as a teenager. The farther she gets from the event, the more complicated it becomes. How does she tell the story of this traumatic moment after ten years go by? After twenty? How does her telling change when she has children of her own? As she grows old? With this form, how a character tells their story is just as important as what the story is about in the first place.

While a shorter form can make constructing a first-person narrative more difficult due to the limited space, it is still possible to manipulate a speaker’s telling in flash pieces. Katie Cortese’s “Neat Freak,” from our award-winning miCRo series, is an excellent example of the different layers possible with this perspective. Cortese’s narrator is obsessed with cleaning in order to drown out the sounds of her neighbor’s children. She writes, “Without seeing their faces, there would be no way to tell it wasn’t torture drawing those screeches, which sound like sheet metal being rent in two . . .” This sound, of course, contrasts strongly with the silence of her own daughter, who was murdered, her screams muffled by soil. While Cortese’s speaker thinks she’s telling the story of the neighbor’s children, the undercurrent of tension truly focuses on the traumatic and unexpected loss of her daughter.

One strategy I suggest is building a timeline for your characters. What are the major events in their lives? Plot it out from birth to death (my students are always a bit too excited about the death part). Your character will tell the story of some event that shaped them, but you might also find that other parts of their lives seep in as well. What are they avoiding saying? What slips out? What, as Mazza asks, has marred their pane of glass?

When I’m reading submissions, I’m always excited to see a first-person story, but I’m looking for something deeper than a strong voice alone—I want the telling’s role in the story to be pivotal to the work as a whole.