To accompany our spring 2025 issue (22.1), we have curated a folio on family secrets (reviews and craft essays), after noticing that several pieces in the print issue include that theme. Here is Sadia Hassan’s review of a poetry collection.

Muddying the Gulf: On Families and Secrets

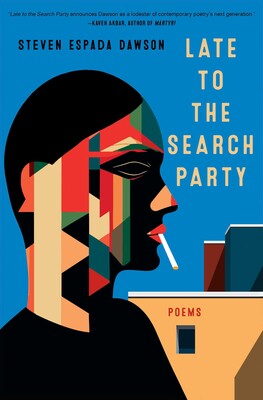

Late to the Search Party, Steven Espada Dawson. Scribner, 2025. 966 pp. $18.00 (paper)

I was asked to write a craft essay about family secrets. I ended up with a long poem about the nation instead. In the poem, I cannot move beyond supposition. I kneel before a bed of ditch lilies—my hands sifting perlite and bark from peat moss and loam— reflecting on revelation and concealment. I watch my elderly neighbor pace the periphery of a flower bed, his wife rifling through mail on their front porch.

As reports of international students being disappeared, some feet from their front door, become widespread, I think about documents. About documentation, distortion, and subversion. How to modulate, through our image systems, metaphors, and syntax, what must necessarily be left out of frame. How to erase our footsteps and the footsteps of others. How to draw a blank when asked “Who crossed what border when?” Is the poem a responsible porter? I cannot be sure. I look to the garden for respite. I look to the poem to hold what the body cannot.

Fifteen years ago I took my first writing workshop, a literary nonfiction course on the archive. Tasked with studying the artifacts of a public figure whose visit had been indexed in the university’s rare-collections archive, I chose Anaïs Nin. Through the cassettes and letters she exchanged with her lover Henry Miller, I learned about her romantic entanglements with Rupert Pole, Otto Rank, and, most infamously, her father, Joaquín Nin. I was surprised by the revelation of an incestuous affair and with so little fanfare. Who but a white woman could afford to reveal so much so flippantly?

In her essay “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision” Adrienne Rich explains that “re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction—is for women more than a critical chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.” I have returned to this essay and the larger collection On Lies, Secrets, and Silence (Norton, 1995 reissue)often as I reentered the emotional geography of my own girlhood and learned to read anew “the nameless, the unspoken, the encoded” silences therein. I have looked to poets like Latif Askia Ba, Donika Kelly, Marwa Helal, Fargo Nissim Tbakhi, Meg Day, and Ladan Osman, who lend us images of freaky antennae bees, centaurs, pyres, gullies, and bare fields to muddy the gulf between the emotional record and public account.

This act of examining my life and exhuming difficult truths—of digging in the dirt with my bare hands for what tender roots can be held, for what fruit is mine to bear witness to—has helped me put language to that vast languageless-ness to which secrets lay claim. And yet documenting the intimate ruptures of one’s family, even in artful, literary ways, can leave one open to criticism, alienation, and misrepresentation by audiences unfamiliar with one’s personal experience or cultural background. To that I say: Fuck it. More than what we owe the poem, or owe an audience, I am interested in what we owe each other and especially those we write about.

For writers contending with the material of their lives while resisting the conscription of their memory and art into the imaginary of militarized nation-states, I would argue there is power in the act of misnaming or in refusing to name at all. That the arts of subversion, misdirection, parable, redaction, hyperbole, flooding, omission, revision, obfuscation, hauntology, and surrealist image-making are formal interventions against the surveilling impulse. Poetry need not be autobiographical to bear witness or testimony. The secret need not be a transcript of interpersonal failures. There are ways to masterfully render the complicated truths of our families while honoring the dignity and privacy of the folks therein. It is our responsibility to avert the unnecessary gaze, to not leave a window open where it had been shut, to respect the rights of others to remain obscure, unnamed, and unintelligible to the public record.

Steven Espada Dawson is one such poet for whom the lyric provides a protective cover. In his poetry debut collection, Late to the Search Party (Scribner, 2025), Dawson—a Los Angeles native and the poet laureate of Madison, Wisconsin—explores the contours of his brother’s addiction while writing through the twin griefs of familial absence and terminal illness. In conversation with Dawson, I learned more about his approach to writing complicated dynamics with such lyrical acuity. “When I write about my family,” he says, “I write in their shadow, not their flesh. The shadow of addiction, the shadow of terminal illness, is almost always wider than the individual.”

“But,” he pauses, anticipating my follow-up question, “you have to draw that line in the shadow yourself, somewhere between your flesh and their flesh.” I hear: Somewhere between your flesh and their flesh is a garden. You, the writer, are the ground between the two.

In Late to the Search Party, Dawson covers the ground between himself and his loved ones with offerings of tenderness. Here, the mundane and miraculous details of a shared life accumulate like silt at the bottom of a clear running river. After a car accident, the speaker’s brother hisses “awake like a soda can,” a banana peel in the sun becomes a bat’s cadaver, and wild strawberries grow “big as a boxer’s fist.” Dawson’s crystalline metaphors are a looking glass, helping us see past the unremarkable and sometimes catastrophic details of one’s life into facets of something more sacred and extraordinary.

In the opening poem, “A River Is a Body Running,” as in others, Dawson invites us to gather and witness a miracle, a moment of intimacy so self-contained, it borders on the solemnity of prayer. Dawson writes:

The first time I found my brother

overdosed, he looked holy. A thing

not to be touched. Yellow halo of last

night’s dinner. His skin, blanched blue

fresco: Patron Saint of Smack.

I am interested here in the act of transformation. Not only does the brother become “holy” in this moment of near-death, he is recast as a patron saint, the very mess he has made of his dinner now a “a yellow halo,” his skin a “blanched blue fresco.” Yet the act that jolts him awake, making him ordinary and unholy again, is an all-too-rare dignified encounter with a cop. We are assembled, watching prayerfully over the speaker, who in turn watches prayerfully over the paramedic speaking softly into his brother’s ear “like a lover.” It is an inverted church scene, a holy site of cops and addicts, but missing is the lexicon of shame that I’ve come to expect from mainstream depictions of addiction or illness. Dawson ends the poem, impossibly:

In the corner

I whittle that used syringe into

an instrument only I can play.

I read in these poem a family secret that might well be hope, be resilience in the face of loss, be a speaker who, even after years of a loved one’s disappearance or illness, continues to build an altar to the possibility of a future gathering. More than any “secret,” Dawson lays bare what the secret holds in place (hope) and what it makes possible (renewed vision, a portal through which to reenter time).

In the poem “Wish,” Dawson assembles a search party inside and outside of his body, this time taking us by the hand and walking us through his childhood home:

The summer

you disappeared I could only fall asleep

in the bathtub. Its porcelain hand cupped

my blueing body. A dozen

candles with their little soulspinched out. I was angry with want.

I wanted to fold your clothes

while you were still in them. I threw a fistful

of downers into my ogling

mouth. Hoped it’d somehow help me

be my addict brother’s brother. It wasn’t just

that night but several

years. I courted addiction like I wanted

its last name. I was assembling

a search party inside my body.

Dawson’s earlier distinction between the shadow of a thing and its flesh feels, to me, as clear as the mechanics of his metaphors. When Dawson tells me, “I write in their shadow, not their flesh,” I understand that to mean he is not interested in the work of reportage or transcription which requires speaking over a living being, but rather the work of translation, of distilling an image to its most salient detail. Writing around the edges of a loved one’s illness or addiction demands a tender attention to aperture, that is, widening and narrowing the field of vision through which readers might take in light or breath as they enter an image.

In “Wish,” Dawson assembles the quotidian as if for prayer—the almost human hands of the porcelain bathtub, the speaker’s blueing body, a handful of downers. Working almost like a conveyer belt, the images move us through a lifetime, from one summer to several years, until we arrive quietly at a final heartbreaking image:

One night, you accidentally burned

the back of my hand with a cigarette. I see the second

-degree scar—pale scarab bubbling back.

You were apologetic, pulled my hand

toward your face. Pursed your lips and blewaway the ember like a birthday candle. You forgot

to brush away the ash.

The kind of loving attention it takes to recall the particulars of a past life might well teeter into translation, what Donald Revell in The Art of Attention (Graywolf, 2007)refers to as “the transformative ecstasy of perfect attention, that sublime instance of being alone with the Alone.” In one assignment, Revell asks his students to translate their original poems into “a nonexistent language of their own invention.” Freed from expectations, the students “find themselves at play among unexacting sounds.” Dawson performs a similar magic in his attempt to translate the ache of his inheritance. The playful music of his lines, scored as much by breath as they are by internal tension, is an apt companion to the reverent atmosphere of these poems. The lexicon of ash, pursed lips, and pale scarabs here feels not only intimate but faithful, transforming a moment of physical harm—a brother accidentally burning the back of the speaker’s hand—to one of succor, of tenderness between siblings.

What early encounter with Nin’s personal materials revealed to me was my unease with public record and my own impulse toward concealment as a means of archiving my own survival. It is from this alter-archive—of notebooks, family photo albums, personal documents, WhatsApp recordings, text exchanges, personal letters, emails, and notes from conversations—that I have translated the raw material of my life into poetry and various hybrid works of nonfiction. In the poetry of my peers, I see a similar impulse to reach into family archives as an act of reclaiming and transforming personal histories.

While certain writers have had the privilege of perfecting the craft of divulgence, others—the cash poor, the queer, the trans and ungendered, the recovering addicts, the undocumented, the mentally ill, the asylum seekers, the second-generation immigrants, the Muslims—have been perfecting the craft of rupture, of rearrangement, of translation and lyrical accumulation, of scoring and rescoring family memories, of packing the gaps and breaks in time with glass (or sugar) as a safety measure and, failing that, layering and re-presenting the image, slant. Who, in a time of crisis, can afford to lose family over a poem or an essay containing a “family secret”?

So much of the common advice to writers says to implicate yourself as you write about others in service to honesty and complexity. However, in writing about my own girlhood, I have found it is not always fair to demand the person harmed go back and share responsibility for the harm caused to them. What feels more important is to implicate systems, so that as you map out what happened where and to whom you also make clear who had healthy choices and why or why not. I am interested not necessarily in the family or the secret, but in what the field of power made possible or impossible with regards to your own story.

What became true of the world when you decided to write into what might otherwise remain haunted? Who held the flashlight for you? Where did you rest your gaze after? How can you cover the ground between the many yous and the many secrets with rahma? I am asking with whom and to what can we be responsible when our families and our secrets are held together by systems of domination and humiliation. Always, to each other and the truth. Surely, to ourselves and the poem. But also, to the image, the metaphor, the leap. It is complicated, but not impossible, to write one’s way through shame and secrecy toward a door wide enough for all of us, a window beyond which lies a garden.

Sadia Hassan is a Somali American poet and essayist from Atlanta, Georgia. She is the author of Enumeration (Akashic Books, 2020), selected by Kwame Dawes as part of the African Poetry Fund chapbook series. Her work has appeared in Longreads, Hayden’s Ferry Review, the American Academy of Poets site, and elsewhere. She is a former Jay C and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing and is currently at work on a debut collection of poetry.