13 minutes read time

To accompany our spring 2025 issue (22.1), we have curated a folio on family secrets (reviews and craft essays), after noticing that several pieces in the print issue include that theme. Here is Shara Lessley’s craft essay on family secrets in nonfiction:

Let Me Whisper in Your Ear: A Craft Essay

Two gorillas crashed a Halloween party in 1975, befuddling their newlywed hosts. For nearly an hour, the primates sat in silence on the thrift-store sofa watching, from behind their masks of latex and fur, as the revelers drank and danced. When offered beer, they pantomimed no. Waved hello to Wonder Woman and the shark from Jaws. One gorilla cuddled a giant rubber banana like an infant. See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil, his partner gestured when asked to divulge their identities. Eventually, the bride pulled her husband into the kitchen. “They’re giving me the creeps,” she said. “Should we call the cops?”

Having traveled nearly six hours from Whittier, California, to Monterey for the chance to pull off their prank, the gorillas, as it turns out, were the bride’s parents. Only many years later did the pair reveal the gag: their rented costumes, a nearby hotel, the difficulty they’d had holding back laughter and not breaking cover. By the time I entered the picture (the newlywed “hosts” became my future in-laws), this “secret” had long been transformed into a story that’s now family legend. In it is the lure of plot, idiosyncrasy, an unexpected revelation, yes. But, too, the opportunity for dialogue, reflection, and connection across generations; that is, a chance to engage the experience from multiple perspectives.

I wish my family secrets centered on tomfoolery. Instead, I’ve written about gun violence, domestic abuse, sexual assault, suicide, and parental stalking. It’s not that I set out to do so, only that I felt compelled to engage, however awkwardly or with uncertainty, the disconnect between perceived “normality” and the reality of my lived experience. Like many people with CPTSD or a history of trauma, as a kid I intuited secret-keeping as a means of self-protection. What I couldn’t have possibly recognized at an early age was the extent to which this kind of concealment fosters isolation, anxiety, and an ongoing sense of exclusion. Requiring self-discipline and encouraging docility, secrecy is a way of controlling the narrative because, put frankly, silence too often serves other people’s needs.

Family secrets have their own unique architecture. Some are sculptural and tomb-like, while others wall in their keepers with government-issued chrome and steel, or the culture’s curtains of opaque glass. Whatever their design, conformity is key; the maintenance of private order and public appearance remains of utmost importance. The majority of family secrets, however, share principles in line with Jeremy Bentham’s eighteenth-century panopticon, a circular prison whose primary means of control is a central tower from which a lone guard can see into any cell at any time.

It’s no surprise that the panopticon’s ingenuity stems from a combination of the prisoner’s noncommunicative state and fear of permanent visibility; that is, self-regulation as a staple of control. As Melissa Febos observes in Body Work (Catapult, 2022), it’s the stigma of victimhood that keeps many writers from sharing their closely guarded histories. “By convincing us to police our own and one another’s stories,” she writes, oppressors “have enlisted us in the project of our own continued disempowerment.”

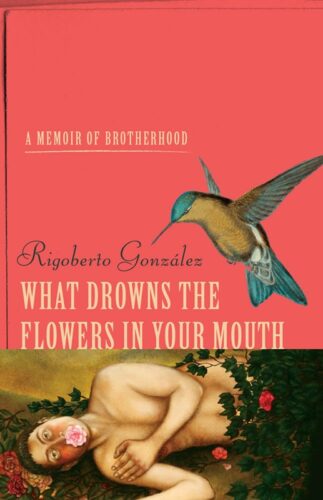

When I first started writing poetry, I was terrified of rendering anything too personal for fear of being labeled “confessional.” Yet, in prose, vulnerability now feels more like agility. “Maybe it’s better for these stories to be out in the world than in our heads,” posits Rigoberto González in What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth (University of Wisconsin Press, 2018), a memoir that considers a Chicano family’s thorny models of masculinity. Essential to the book’s portrait of grief and desertion is the early concealment of the author’s sexuality, a “secret” whose unveiling turns out to be refreshingly anticlimactic, as González’s brother has long suspected, and accepted, his sibling’s romantic attraction to men.

What’s more complex, however, is how patterns of silence and generational trauma inevitably influence the brothers’ private lives, and how each one internalizes and then comes to resist the more harmful parts of this legacy. Of leaving a lover whose derogatory control and manipulation he accepted and kept hidden for too long, González writes late in the book, “How good to have a direction and a destination. How comforting to know that every step forward made a memory of the previous step.”

In What Drowns the Flowers in Your Mouth, González’s newfound sense of “direction and a destination”—his purposeful moving forward—arrives via literary attentiveness and narrative intention. In this case, the real-time decision to liberate oneself from an abusive partner is of great personal consequence, while writerly retrospection (i.e., how González’s self-advocacy subverts toxic relationships modeled by his older male family members) serves as an act of empathy not only for the author but also for those readers who’ve shared similar experiences and feelings.

Building on González’s example, if the silence of what isn’t told leaves a lasting imprint, why not—with consideration and ethical care—shape the telling? To make the network of feeling around a particular experience perceptible on the page. Or as Molly Brodak puts it in Bandit (Grove Press/Black Cat, 2016), an account of her gambler-father’s descent into bank robbery, “The facts are easy to say; I say them all the time. They leave me out. They cover over the trouble like a lid. This isn’t about them. This is about whatever is cut from the frame of narrative.”

What I’ve discovered in writing family secrets is that the practice is less about those things that are “exposed” than finding a structure for what’s disclosed. An interesting word, “disclose”—one that harbors an unspoken set of contradictions. Etymologically embedded from the Old French and Late Latin are “closture” (a fastening, hedge, wall, fence) and “clausura” (a lock or fortress). But to my mind, the contemporary schemas of close that hang on the prefix “dis” also suggest both verb (to shut or end) and adjective (to be near). Taken together, this combination implies that conclusions need proximity; to close a door, for instance, one must be close to the door. Resolution via disclosure, in other words, requires intimacy. But what if it’s possible for essays and memoirs that feature family secrets to do more than restage the past? What if disclosure can foster alternative forms of intimacy?

Take, for instance, The Blessing (Milkweed, 2019), in which Gregory Orr narrates killing his younger brother, Peter, during a childhood hunting accident. As kids who carry the burden of secrets often frame themselves as their stories’ protagonists, thereby sourcing their actions as the sole impetuses for communal suffering or shame, Orr’s retelling of The Blessing’s central event provides reconstructive insight and the opportunity to build a “shelter . . . where human meanings begin.”

While it eventually moves away from Peter’s shooting and travels well into the narrator’s adulthood, The Blessing is a matryoshka of family secrets. Orr’s physician father’s “denials of horror” and workaholism lead to excessive alcohol and amphetamine use, as well an overdose by yet another young son who consumes the parent’s forbidden pills after discovering them in a drawer. That Orr’s father, too, accidentally killed a friend during adolescence while skeet shooting is “a dark and shameful secret” that likewise hovers over The Blessing. “It is not a story he has ever told to anyone I know,” writes Orr. “Not a single word about it has ever passed between him and me all these years. My mother spoke her single, cryptic sentence about it to me the day of Peter’s death, and then she, too, would never mention it again.” Yet the laying down of this fact in print presses against Orr’s isolation.

Rather than allowing the secret to rest in the era’s prescribed silence (“In those days, people didn’t talk about things like that,” reflects the physician patriarch on unbearable losses), The Blessing acknowledges the numbness and confusion of the twinned shootings and their aftermaths. In fact, it’s Orr’s self-confrontation via his memoir that makes possible empathetic hindsight and newfound consolation. That the tragic companionship between father and son went unsaid between them no longer matters as The Blessing serves as an intermediary, a place where the pair’s grim ordeals finally connect and overlap.

Of the arguments against disclosure in creative nonfiction, navel-gazing, revenge, and exploitation (i.e., “trauma porn”) strike frequently and hard. While I’ve read essays and memoirs pejoratively labeled with the aforementioned terms, these descriptors often seem less the result of some ethical breach or egoism than the authors’ struggle to find a structure or experimental framework that best shapes the material. Put simply, it’s as if the secrets themselves consume the narrative. To my mind, the most engaging and memorable writing on the clandestine renders not only past experience but wider patterns about the nature of being or culture at large. Consider these wildly varied and compelling examples, each of which hinges on family secrecy while also building dramatic momentum and suspense that result in emotional complexity and vivid insights:

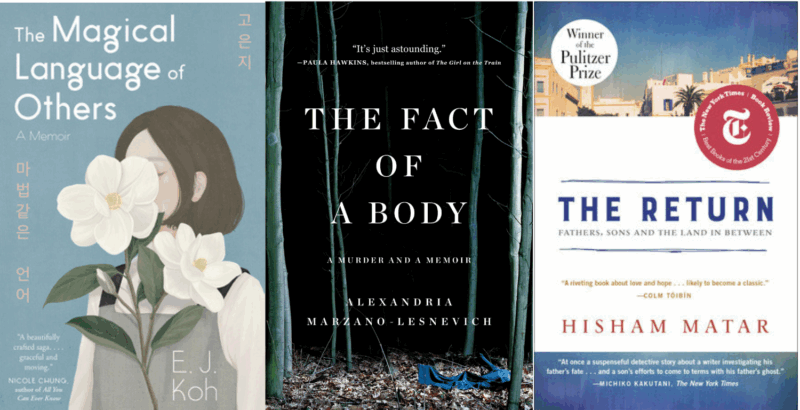

Coming-of-Age / Epistolary / Mosaic: When her parents move to Seoul for professional and financial advancement, leaving their high school daughter to fend for herself in California, E. J. Koh answers the betrayal of absence and abandonment with The Magical Language of Others (Tin House, 2021), a hybrid memoir that stitches together translation, letter writing, diary entries, internal dialogue, poetry, remembrances of the Jeju Island Massacre, the ritualized diction and metaphors of Catholicism, generational arguments, cultural legends, the communication (sometimes clear, sometimes lapsed) that takes place among family members and, of course, the silence between all of these that tells another kind of story altogether.

True Crime / Personal Narrative: In The Fact of a Body (Flatiron Books, 2017), Alex Marzano-Lesnevich revisits closely guarded memories of childhood sexual abuse that resurface after their law firm takes on the case of confessed pedophile and murderer Ricky Langley. Rich with investigative reporting and unflinching in its layered depictions of secrecy and suffering, The Fact of a Body considers the interplay between fact and recollection as it relates to public and private crimes, as well the inner conflicts that arise when considering reparation and punishment.

Portrait / Reportage / Memoir: Hisham Matar writes of his father’s work as an opposition leader organizing against notorious dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. Journeying to Libya as it follows Matar’s quest to learn the fate of his imprisoned parent, The Return (Random House/Viking, 2016) moves back and forth across multiple continents and periods of time as the memoir uncovers hidden identities, secret fundraising efforts, the organization of sleeper cells and political dissidents, and previously unknown details about Tripoli’s notorious prison, Abu Salim. Not only an insightful historical and political portrait but a story of war and family resilience, The Return is an elegiac mystery that validates the importance of art and invention in times of perpetual strain and uncertainty.

If the above examples demonstrate how writers write family secrets, what about why? For some of us, disclosure serves as a countermeasure to silence, a record in the material world for what would likely be otherwise ephemeral. For others, the action of writing is corrective, a means of resistance. Articulated on the page, a secret—and the systems or circumstances that incentivize its keeping—can be studied, examined, analyzed, destigmatized. Maybe our impulses stem from curiosity or pain, or the dizzying confusion of isolation. Perhaps, in writing about family secrets, our initial desire for resolution leads to an acceptance of things irresolvable. Perhaps, in the past, some of us didn’t trust the authorities we were encouraged to, and only now feel safe enough to start sharing. Maybe, for some, the creative act of self-inquiry is life-changing or saving. Maybe the players implicated in our secrets have been forgiven or are long dead, or frankly don’t give a shit about their business being told. Maybe “why” is a combination of these reasons. Or none. Maybe there is value in simply giving creative attention to those experiences that hold our attention. And that, quite honestly, is reason enough.

Let me offer a final model, one I admire for many reasons, but especially for its raw lucidity and inventive use of anti-linearity. Marcelo Hernandez Castillo’s Children of the Land (Harper Perennial, 2020), a lyric memoir of struggle and of grace, chronicles the layered secrecy necessitated by growing up undocumented in the United States. In one scene near the end of the book when he’s no longer in need of hiding his residency status, Castillo dissolves copies of expired paperwork, permits, and forged identification cards in a bucket of bleach, water, and glue, in what he calls “a baptism of all my former selves.” As Castillo explains, “I began molding the mixture into a four-legged thing. It could have been a horse, or a dog, or a cow.” The active examination and then re-modeling of Castillo’s formerly undocumented paper trail beautifully enacts what Sven Birkerts describes as creative nonfiction’s ability to “anchor its authority in the actual life.”

In the figurative and literal dissolution and resculpting of pulp and ink, Castillo disrupts secrecy’s long silence. Inverting the myriad disguises and erasures necessary to survive in an America that categorizes his family as criminals, Castillo offers a cogent example of the transformative possibilities of writing about experiences once concealed or unsaid. “I made many more four-legged things,” he recalls of the project, “and placed them in the sun to dry, to harden. . . . They were a record of myself that held my secrets.” Here, instead of fear and insecurity alone, are powerful new shapes: companions that carry within them the old stories. Listen, they say. Let me whisper in your ear . . .

Additional Recommended Reading:

In the Rhododendrons: A Memoir with Appearances by Virginia Woolf (Algonquin Books, 2025), Heather Christle

Consent (Pantheon, 2024), Jill Ciment

The Riots (University of Georgia Press, 2011), Danielle Cadena Deulen

Abandon Me: Memoirs (Bloomsbury USA, 2017), Melissa Febos

Somebody’s Daughter: A Memoir (Flatiron Books, 2021), Ashley C. Ford

Crazy Brave: A Memoir (Norton, 2012), Joy Harjo

And Now I Spill the Family Secrets: An Illustrated Memoir (HarperOne, 2021), Margaret Kimball

Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner, 2018), Kiese Laymon

Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping (Scribner, 2023), Shane McCrae

Whiskey Tender: A Memoir (Harper Perennial, 2024), Deborah Jackson Taffa

Secrets of the Son (Mad Creek/Ohio State University Press, 2024), Mako Yoshikawa

Shara Lessley is the author of The Explosive Expert’s Wife (University of Wisconsin, 2018), Two-Headed Nightingale (New Issues, 2012), and coeditor of The Poem’s Country (Pleiades, 2018), an anthology of essays. A former Stegner Fellow and NEA recipient, Shara’s nonfiction has twice been listed as “Notable” in Best American Essays and appeared in AGNI, Prairie Schooner, The Kenyon Review, The Gettysburg Review, Bennington Review, and The Southern Review, among others. She is creative nonfiction editor for West Branch.

![Special Feature: “Mrs. Williams [Or, A Study of Postmodernism and the Many Ways That Walls Are Broken]” by Julie Marie Wade](https://www.cincinnatireview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Wade-Website-440x264.png)