Assistant Editor Lily Meyer: Several weeks after the United States withdrew from Afghanistan and the Taliban returned to power after a twenty-year insurgency, the Afghan writer Hussain Shah Rezaie, who has refugee status in Indonesia, sent the Cincinnati Review this moving account of his first call home after President Ghani’s government collapsed. As an American magazine, we understand that our country’s politics are deeply entangled with Afghanistan’s, and we are honored to be able to publish Rezaie’s clear-eyed telling of one piece of his family’s story.

Weight of Words

I couldn’t even utter the soothing sentence It’s going to be fine, which has always appeared on my tongue when somebody I am close to needs comfort.

I managed to talk with my mom on the phone two days before Kabul fell to the Taliban. It was an arduous call to arrange. I had watched hours of JusCall ads, hoping to connect with my family in Afghanistan, but the service had stopped working seven months before, and I could not reach them in any other way. The only news I heard about my hometown came from distorted social-media images of battles between local resistance fighters and Taliban militants. My eyes stopped closing at night. I worried and worried. Despairing, I called my aunt on WhatsApp to see if she’d heard anything about my family. She surprised me by connecting me with my mom through a regular call from another phone.

Nothing can take the glee from a mother hearing the almost-forgotten voice of her son from thousands of miles away. My mom’s joy rang in my ears as though my voice was the only thing she wanted to hear in the world. It made me happy to delight her after so many years apart. She spent a minute expressing her rapture and gratitude at finally hearing me. It made me cringe knowing my aunt was still on the line—sweet talk has always made me drop my gaze to the ground. However, our conversation took a different turn when I asked about her day, and about my little brother and sister’s situations.

She had heard of the atrocities the Taliban were committing in the areas they captured, especially in the neighboring district, Malistan. There, the Taliban slaughtered dozens of civilians and gouged a woman’s eyeballs out of her skull, then hauled her to their truck and dragged her around the village.

But it was not death my mother spoke fearfully of. Due to her adamant belief in God, she could justify death as Allah’s will, even if the Taliban caused it. Her voice trembled, and I heard her restrained sobbing as she spoke of my sister’s situation. She had heard of the viral public announcement that the Taliban made in Badakhshan, demanding that girls above fifteen and widowed women would be enslaved sexually to their Mujahideen. She had no way to reconcile her fear that that circumstance would be my young sister’s fate. Since no place inside Afghanistan was a safe haven for my sister to go, my mother felt completely helpless, as did I.

It wasn’t the first time I found myself powerless to change my family’s deteriorating situation. Every time in the past seven years of my life as a refugee that I’ve heard my family cry, I feel more helpless than ever before. The feeling has grown so strong that recently I’ve been asking myself if I am even a man, in the traditional sense of a person whose primary responsibility is taking care of his family in the face of dire insecurity.

This time, my words seemed so weightless compared to the dark future awaiting my country that I couldn’t even utter my common soothing sentence: It’s going to be fine, Mom. The weight of it clustered at the bottom of my throat. A helpless silence lasted for a minute between us before my aunt broke the silence by saying to my mom, “Khoda Mihraban ast, Aughai.”

Now months have passed since the foreign troops left, taking the hopes of millions of Afghans with them, and the Taliban took complete power over Afghanistan. I lost contact with my family until three weeks ago. Their situation still takes all sorts of turns in my head, depending on what mood I am in or what time at night it is. Often I picture them almost killed by the Taliban before I bring them here to me. But that’s as real as my imagination.

Finding the right words unburdens my pain. That’s what I learned in the past two years. And it helps me to breathe more normally than other refugees who do not have the aid of words on their side.

Artist Statement:

During my seven and half years of statelessness in Indonesia as an Afghan refugee, I have learned to turn my suppressed feelings of pain into words. I suffered through the trauma and tragedy that Afghanistan faced in June, July, and August 2021 from thousands of miles away, but my family, relatives, and home are still there. My helplessness and inability to contact them pained me throughout the day and kept me awake at night, living their situation in my mind. And I decided to turn some of those into words, hoping writing would have its usual healing effect.

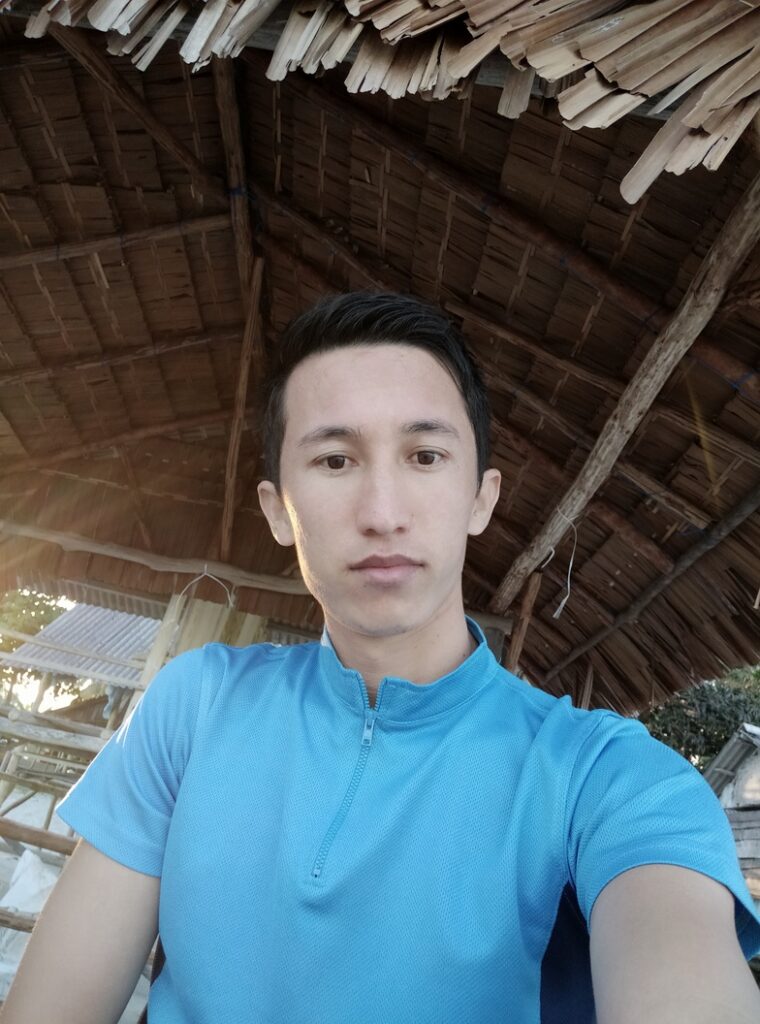

Hussain Shah Rezaie is an Afghan refugee who has lived in Indonesia for more than seven years. He is a survivor of war and a self-professed writer. He writes essays, short stories, and poetry, and is at work on an autobiographical self-help book. His work has appeared in the Jakarta Post.

Excellent, hope to see more from you