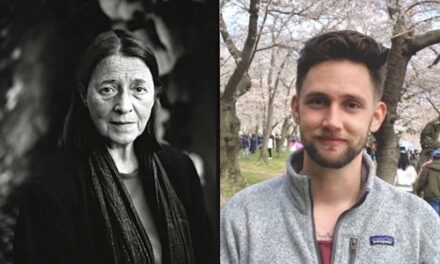

Associate Editor Molly Reid: In the short essay “See Through,” Alex Myers serves up magic: a rabbit pulled out of a rabbit pulled out of a hat. He lets allusion and implication pulse underneath a seemingly simple scene at the Greek room of the Museum of Fine Arts, which he first visited as a child and then as a young adult. Focusing on the anatomy of the urns and statuary, with frequent repetition of the word dick, Myers evokes complex layers of meaning: genitalia as arbitrary, as sacred, as profane, as wonder, as art, as fascination and letdown. When we return to the question asked in the beginning of the piece—”Why are all their dicks so small?“—we have a new understanding of what is being asked. This one is a stunner.

See Through

In the Greek room, my brother studies the urns. Heroes, their helmets crested ornately, crouch behind shields, swords at the ready. My brother whispers: Why are all their dicks so small?

Then he finds the amphora with the Satyr whose prick wraps halfway around the jug. He circumnavigates it, eyes wide with approval.

The room, to me, is haunted. Statues bleached white, their limbs amputated. Some are just torsos. And some, worst of all, are just heads. Dozens of them: round sightless eyes staring at me.

My brother is seven and I am five. This is the unbridgeable expanse between us. It will always be that way. Another expanse between us, back then: he is a boy and I am a girl. He knows things that I don’t know. Like about the dicks on the urns. Our mother has been good with picture books, so I am not completely confused. I try to study the urns like him, but all those blank eyes bear down on me.

I have a comic-book version of the labors of Hercules, another of the voyage of Ulysses. They have taught me nothing of dicks, small or otherwise, but plenty about the gods. How Zeus can transform, how Athena can disguise. How the gods are always playing tricks on us, putting what we want just out of our reach.

My brother has moved on from the Satyr. Now he admires a case of swords. Leather handles long since eaten away, iron blades corroded. They are dicks of a different sort; I sense that even then.

In college I learn that the purpose of art is the feeling it inspires in the one who beholds it. I write this definition in my notebook and study it for an exam, which I need to pass in order to fulfill my core requirements.

The class takes me back to the Greek room at the Museum of Fine Arts. This time without my brother. This time, I am here as a boy, blue jeans and sweatshirt and baseball cap, though still no dick.

It’s all the same. Still the eyes staring at me. Still the disembodied torsos. Still the swords in their cases, no more corroded than before. I take idle notes and wonder what was interesting to my seven-year-old brother.

Then I drift over to the vases and amphorae. I feel voyeuristic as I search for the Satyr, satisfied when I find him, his three-thousand-year erection still going strong.

And there are the heroes, still crouched behind their shields, still standing with swords upraised, their meager genitals on full display.

Almost, I can picture my brother and me standing there, our eyes level with the bottom of the urns (now I have to bend my knees to get a good look). My brother’s gaze intent, measuring, comparing, holding up art against reality. Finding it wanting.

I am tempted to ask my professor: Why are all their dicks so small?

But I worry that he will have an answer.

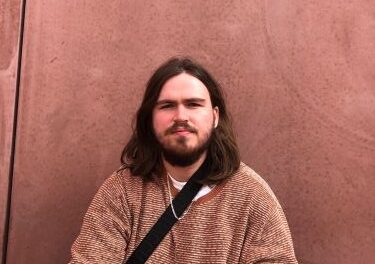

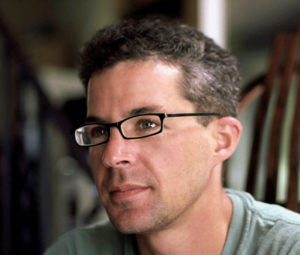

Alex Myers is a teacher, speaker, and writer who works with schools and other organizations to be gender inclusive. His essays have appeared in The Guardian, Slate, Salon, Good Housekeeping and literary journals such as Hobart and Cutthroat. Alex also writes fiction. His debut novel, Revolutionary (Simon & Schuster, 2014), was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award, and his novel Continental Divide is forthcoming (December 2019) from University of New Orleans Press. Full details at: www.alexmyerswriting.com.

For more miCRo pieces, CLICK HERE