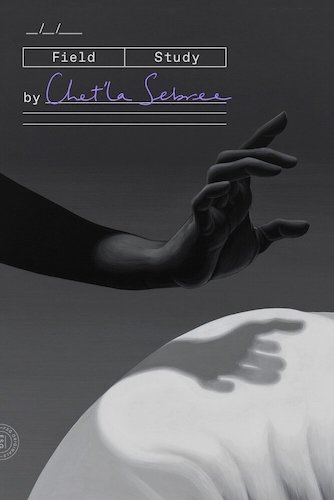

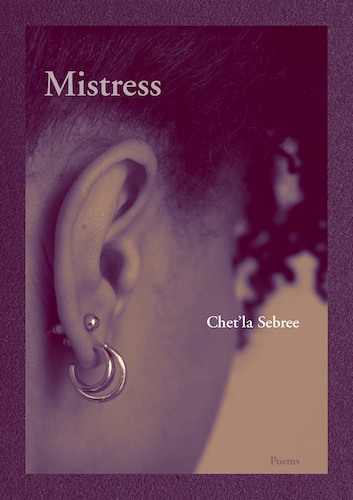

Assistant Editor Holli Carrell: This week, poet and essayist Chet’la Sebree will visit the University of Cincinnati as part of the English Department’s Visiting Writers Series. Sebree is the author of Mistress (New Issues Poetry & Prose, 2019) and Field Study (FSG Originals, 2021), winner of the 2020 James Laughlin Award. A book-length poem in prose blocks, Field Study is an intimate examination of love and heartbreak, interracial relationships, Blackness, womanhood, healing, and self-love. Field Study is also a remarkable, genre-defying work: Sebree deftly collages her observations and reflections with quotations from acquaintances and friends, influential Black scholars, writers and artists, film and TV characters, and many more sources. Ahead of her reading, I spoke with Sebree about Field Study, Mistress, writing persona poems, experiential research, her forthcoming essay collection, and more.

What was the best or most exciting aspect of writing Field Study? And what was the most challenging or complex aspect of writing it?

Making it up as I went was both the most exciting and most challenging part of Field Study. The book initially started as an essay I wanted to write on interracial desire. I quickly abandoned the idea of a traditional essay for a lyric one, but even that felt wrong. I moved, then, from lyric essay into the prose-poem form I adopted for the book. Still, though, I wasn’t sure how it would arc. But there was something exciting about inventing this blurred form born of ones I’d already known, about pushing boundaries and seeing where the language took me. At the same time, there were moments where I was unconvinced this stitched narrative would translate to others. I wanted the book to feel like many synapses firing at once, but I didn’t want the poem to be so dizzying that people abandoned it either.

The poems in Mistress present an intimate cross-generational dialogue between two Black female speakers—Sally Hemings and a contemporary speaker. How did your research methods differ between your first book, Mistress, and Field Study?

The research for both started similarly. With both, I started by reading. I went to books, my home base, to learn more about [Sally] Hemings and to give language to my experiences of contemporary Black womanhood. Then, for both, I pivoted outward into experiential research. For Mistress, I tried to construct Hemings’ world through my experiences at Monticello, where she was enslaved, and in Charlottesville. With Field Study, I lived in my world—congregated with my friends, traveled to places I loved, looked at art. I think the main difference with Field Study was that I was open to the universe and all she had to offer me. I wasn’t looking for truth quite so narrowly, as I was when I first started writing about Hemings. I think I was trying to find her in Mistress, even had an early poem called “Searching for Sally.” For Field Study, however, I knew who I was but wanted to understand myself better in conversation with the world. Research meant I had to be fully present in the sound of my shoes on the street, the gentle touch of canoodling strangers, the words of the people I loved.

Was there a specific moment while writing Mistress that you knew the poems about Sally Hemings needed to be written in her voice? Do you have any advice for writers considering using persona to inhabit historical voices and subjectivities?

Early on in my research about Hemings I wrote poems born of the archive, of historical research, of the record. But I realized how much of this version of Hemings I would construct would continue to live in the mouths of white men, as they were the makers of the archive. I didn’t want to recreate that inter-generational silencing, so I started writing poems in her voice. But it took me years to find a voice with which I was comfortable, not wanting to inflict harm through affect or assumptions. I developed the persona through the archive but also through experiential research—trying on a replica of an 18th century corset, living in Charlottesville for a year to experience all four seasons, spending time in the quiet of Thomas Jefferson’s bedroom. This also meant reading and watching other people’s manifestations of Hemings and determining how my iteration of her would be different. And it took me a while to find her voice because I realized there was something inherently violent in what I was doing—occupying the voice of someone who has been robbed of one.

I think it’s important to recognize this potential violence, just as it is important to know why you’re trying to write through someone else’s voice. It’s not enough to just want to write about someone; it’s not enough to realize that our desires to write about someone also have the capacity to do harm. In an interview conversation, which led to the writing of “Je Suis Sally,” I finally understood why I wanted to write about Hemings. I was trying to find my own liberation through liberating her. In my early twenties, I found Hemings’ circumstances so devastatingly insurmountable: an enslaved woman born of master-slave violence who finds herself in a similar situation, which produces six children; an enslaved woman who loses four of those children—two to infant death and two to them escaping enslavement and passing into white society; an enslaved woman whose enslaver frees their other two children in his will but not her (though she is “given her time” and allowed to go free by his daughter). My circumstances paled in comparison to hers, so if she could move through then I could too. But in this realization, I also understood I couldn’t liberate her any more than she could liberate me and that in the archive I wouldn’t find Hemings just how other people saw her, including me. “Je Suis Sally” was the second poem I felt I wrote successfully in her voice. This was five years deep into the writing. But from there, it felt the rest of the persona poems clicked because I finally understood why I was writing about, to, through her.

How do you know when a project is better suited for poetry or prose?

I don’t always know, if I’m being honest. Each piece requires something a little different and sometimes I don’t know until I’m in the throes. Like I mentioned earlier, Field Study started off as an essay. But I discovered I had nothing concrete I wanted to say about interracial desire. Instead, I wanted to meditate, ask questions, linger in thought the way poetry affords, in the way that sometimes resists sense or knowing because I had no answers, only a hunger to know more. I often say I like poems because you can abandon readers in an ocean of their own emotions. Essays sometimes feel more like a guided tour. And sometimes I’m ready to guide people; other times I’m not. I think deciding which form a piece should take both requires listening to the subject matter and the self. Where does the subject want to go, and where are you willing to take it? For example, I call Field Study a book-length poem in prose blocks. I have friends who call it a lyric memoir. Both are true, but the one I say is the one I am most comfortable with because I wouldn’t have been able to write the book if I were calling it a memoir in the process. Sometimes, the line is blurry because you need it to be.

Can you share a little about your next project? I read on your website that you have an essay collection forthcoming with The Dial Press next year. Congratulations!

Yes! Thank you. I’m working on my debut essay collection, which is both exhilarating and terrifying. The essays are about my relationship to ideas of home and belonging through domestic and international travel as a Black American woman. As I write them, though, they’re turning into essays about inheritance and parenthood, about chosen family and exile, about dreams and realities. I’m still learning what they’re about as each unfolds, which is, as I mentioned before, the best-worst part about this work.

Chet’la Sebree will read as part of the English Department’s Visiting Writers Series this Tuesday, February 27th, at 5:30 p.m. in the Elliston Room (646) of Langsam Library.

Chet’la Sebree is the author of Field Study (FSG Originals, 2021), winner of the 2020 James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. She is also the author of Mistress (New Issues Poetry, 2019) selected by Cathy Park Hong as the winner of the 2018 New Issues Poetry Prize and nominated for an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work—Poetry. Her debut essay collection is forthcoming from The Dial Press in 2025. Sebree has received fellowships from Baldwin for the Arts, the Delaware Division of the Arts, the Hawthornden Foundation, Hedgebrook, the Hermitage Artist Retreat, MacDowell, the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies, the Stadler Center for Poetry, the Vermont Studio Center, and Yaddo. She is an assistant professor of English at George Washington University.