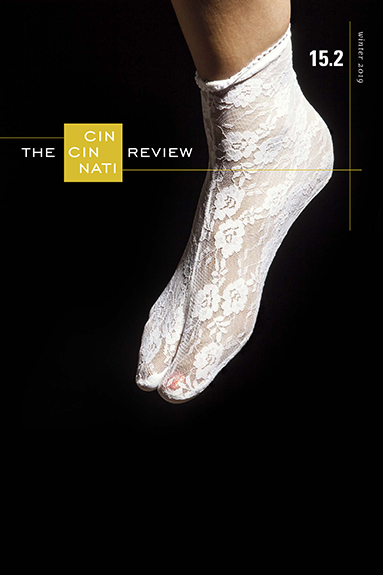

We’re getting close to the release of Issue 15.2, which should arrive from the printer in the next few weeks! In advance, we’re pleased to share the cover, with artwork by Emily Hanako Momohara:

We also want to take this opportunity to explain a change in our editorial practices. Generally, we follow the industry Bible, The Chicago Manual of Style, with zeal. In the past year or so, though, we’re realizing that we have some quibbles with section 7.53, “Unfamiliar words and phrases from other languages.”

Chicago (as we like to call it) says,

Use italics for isolated words and phrases from another language unless they appear in Webster’s or another standard English-language dictionary.

The convention stems from the desire not to confuse readers, to make clear that the word in italics isn’t just some English word they’re unfamiliar with—or a typographical mistake.

The effect, though, is that the foreign language is made “other” by that stylistic choice. And for bilingual (or multilingual) authors, English exists alongside of and is interwoven with the other language(s), so it feels false to distinguish between them in that typographic way.

As a result, as Thu-Huong Ha points out in this article on Quartzy, “Over the last decade, there has been a shift away from enforcing italics on non-English words in publishing. And the decision to italicize or not has prompted authors and editors to ask for whom they’re writing, and to question assumptions about the experience of reading.”

We’re part of that shift. Starting with Issue 15.2, we’re updating our house style, that list of rules that diverges from Chicago: When a foreign language appears in our pages now, we’re going to leave it up to the author whether to italicize or not, as long as we’re consistent within a piece and avoid confusion.

So, it’s not an oversight that Sarah Blackman’s story “The Key to the Fields” in that issue has italicized phrases in Arabic, but when Dorothy Chan’s poem “So Chinese Girl” names particular Chinese dishes, they appear in Roman text. We’re going to be consistent within our inconsistency—and we hope that the Chicago editorial staff considers a different way to approach this complex concern in their next edition.