In our series of posts written by our contributors, the latest is a reflection by poet Kate Partridge, whose poem “Meditation with Grass Fire and Tumbleweed” appears in our Issue 20.1. Partridge shares some experiences and thoughts behind her poem—but also a meditation on studying motion.

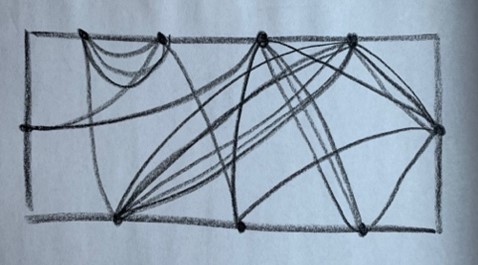

Kate Partridge: A colleague of mine often attends meetings with a piece of white paper laid out on the table in front of him. Each speaker forms one discrete point. As conversation moves, he traces it across the page:

At first, I interpreted this habit as a closed system, a little study of how our discussion was contained. Increasingly, I see it as an invitation to continual opening.

*

The poem I recently published in the Cincinnati Review is called “Meditation with Grass Fire and Tumbleweed,” and it grew out of at least three separate poem drafts that felt incomplete until woven together around the idea of loss. (The title nods to one of my favorite poems, Robert Hass’s “Meditation at Lagunitas,” which begins, memorably: “All the new thinking is about loss. / In this it resembles all the old thinking.”)

When I began this reflection, my first instinct was to attempt a return to my own “old thinking,” or at least to revisit its artifacts. I first scrolled back through my phone for photos of the tumbleweed.

For several weeks in early 2022, the tumbleweed hung out in a corner of the garage that contained my writing desk. I feel confident that I took at least one picture of it for reference, although I wasn’t quite sure what for.

I brought the tumbleweed inside from my yard a few weeks after the Marshall Fire, the sudden burn that led to two deaths and significant destruction of property in Boulder County, about fifteen miles north of my home in Denver.

My tumbleweed photos were gone. Or perhaps they never existed.

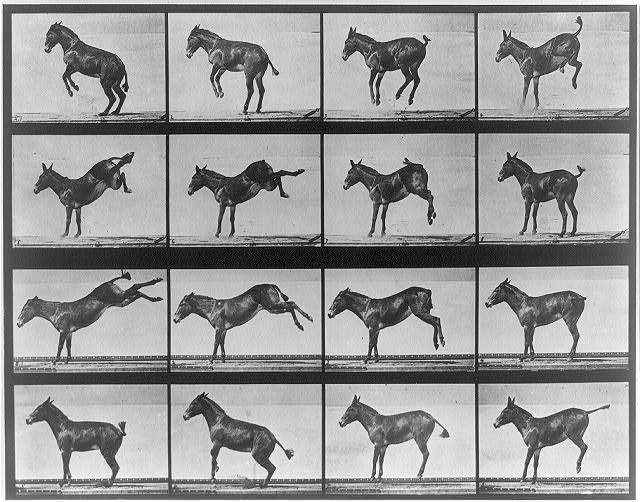

I do remember, in the summer that followed the Marshall Fire, clearing out storage space on my phone. During the COVID years, I had accumulated so many images that, like Muybridge’s motion studies, inscribed my experience of looking over and over again at the same plants, animals, and landscapes (mainly, the views from the front and back windows of my house).

Deleting these photos felt in some way like excising evidence of how much time I had spent in one position during those years, in one static vantage point that nevertheless was excellent for revealing time.

Without the pictures of the tumbleweed, I instead found several time-lapse images of the wildfire online. The shape of its final reach remained familiar: a many-sided figure that was, of course, shaded in red.

Revisiting its outline reminded me, however, of how much of wildfire is defined by speed. It arrives suddenly, followed by sudden winds, surprise ignitions, leaps of flame across boundaries. Everything that follows tends not to stay in tidy, distinct frames.

*

In the last ten years, I have moved around the West in a way that I often describe as a series of discrete points: Alaska, Los Angeles, Colorado.

The first move was part accident, part leap, but over time, I’ve felt drawn to remain in places that still feel strange to me. As someone who grew up in the South, I experience every detail and every season as new, even after years living here.

For instance, in LA, I lived in the attic apartment of a house that had a sticker on the back door indicating how many people and pets lived there, for the use of the fire department.

Within a few months of my move there, a fire burned across the lip of the canyon where I lived, close enough that we were in the zone of a pre-evacuation order. An actual evacuation never came.

The same was not true for my friend in Colorado, who arrived at our house to wait out the flames as the Marshall Fire approached her apartment. This moment is the advent of the poem, although in its final form, the poem came to contain things that happened chronologically beforehand or across a span of time.

*

In this poem, I see myself returning to these places of edge-ness, where the imagined networks of safety around us seem on the verge of failure. At the risk of aestheticizing destruction, I want to look at its forms.

The Marshall Fire was, in fact, two different fires that began at a distance and joined. Both were caused by humans. Attributing fault in such a situation does not necessarily resolve anything, nor does a poem.

From the time-lapse map of the fire, I traced its movement from point to point. I thought that revisiting its motion might help me remember something about what it’s like to watch a distant fire on a screen, but the resulting sketch told me nothing real. And it was ugly.

*

The first time I drove from the Denver airport into the city, a tumbleweed passed (as they commonly do) over the highway that cuts across the high plains.

I didn’t want to be tumbling anymore. In fact, on that trip I was looking for an apartment in the city.

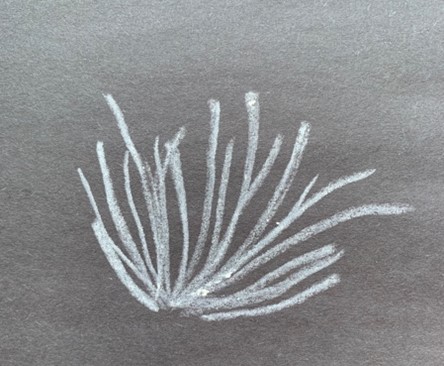

But the structure of the tumbleweed itself—the tension between haphazard falling and connection at the base—continues to travel with me as a metaphor.

If I had to trace a motion study of this poem, it might look like a sketch of a tumbleweed:

Ordinarily, we think of plants as moving outward, from seed to full bloom. In this case, I think the poem asked for the opposite approach to also exist. Each time the poem furls out an idea, it returns back to its base: fire, loss, a root, a place where something has the potential to start again.

I imagine the base, in this case, as the poem’s inciting incident: my friend’s arrival. In an etymological sense, though, as well as a practical one, I might just as easily say that the poem begins on the highway with the tumbleweed, or with the ignition of the fire. Its meditation is formed by the action of moving toward each event again from new angles.

In this way, the poem doesn’t reach a conclusion, although it does end with a mirrored action: a departure, a literal opened door. I value poems for their action, and how they draw the reader into continual questions. They unsettle more than they conclude—but this is, in its own way, a restaging for the next place to look.

*

Kate Partridge is the author of two poetry collections: Thine (Tupelo Press, forthcoming 2023) and Ends of the Earth (University of Alaska Press, 2017). Her poems have appeared in Copper Nickel, Field, Michigan Quarterly Review, Yale Review, and elsewhere. She teaches at Regis University in Denver, Colorado.