Associate Editor Taylor Byas: When I slipped into writing ruts in the past, there was always a quick fix: read more. A few pages into a poetry collection, and I’d come across a word that would start me up like an engine. Language would come back with a vengeance for being forgotten, and I would have the skeleton of a new poem within the hour. Over a year ago, this strategy was such a sure thing that I could bet on it. And then my PhD exams happened.

Over the course of the exam process, I was flooded with other voices. I was deeper in language than I’d ever been, with centuries of Black women’s words and rhythms waltzing around in my mind. When I met with some of my peers, I joked that I’d been reading so much that the poems would write themselves when it was time. But when I tried to write poems during the exam year, I found myself too overwhelmed and stressed. Just wait until the summer, I thought, I’ll be ready then.

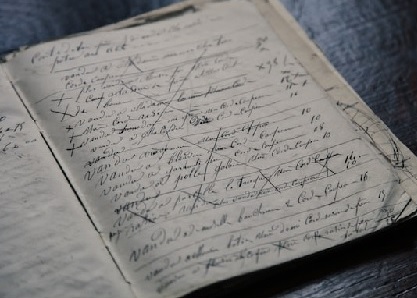

When the summer came and went, and I’d failed to produce anything substantial, I tamped down my anxiety by pushing back the goalpost. I had only managed to pen short letters to friends or the occasional journal entry. In a notebook, I soothed myself—you needed the rest from poems, you’re burnt out, take it easy. But my dissertation year loomed overhead like a highway sign, and eventually I would have to pass under its shadow.

My dissertation year began this August. I started to make a habit of sitting down at the computer and opening a fresh Word document, just seeing what would happen. After catching COVID-19 for the second time in July, I was still struggling with brain fog, and words came slower than usual. I started a poem, erased it all, started again. I spent minutes just staring at the cursor blink at me: an infinite tally for the time I was wasting, a constant little wound scarring the page I couldn’t dare to fill. But after a few failed sessions of this, I turned again to my journal and stumbled across an answer:

I’m feeling something close to fear. I haven’t written in so long that I feel like whatever I do write needs to be good now. I am scared I have forgotten how to write something good. I am scared I have forgotten how I write.

The pressure to churn out a solid first draft paralyzed me. My empty Submittable queue mocked me when I logged into my account. Trying to write had become a stressful enterprise, so stressful that I’d begun to avoid it. But then, magic.

At the beginning of September, I was cleaning out stacks of old papers from my office and dug up some student work from a fourth-grade poetry workshop I’d taught during the summer. That day, we were learning about rhyme scheme, and had spent the session writing small, rapid-fire poems on random topics with random rhyme schemes the students selected. I’d done the exercises with them, and found small bursts of my own writing in the stack. My own handwriting was nearly illegible because we’d timed ourselves, and I was fully invested in playing the game and having fun.

I felt the distance between the poet I was in that summer class, who handled language like bright Legos that could be put together in endless configurations, and the poet who was holding that old stack of papers, trying to remember the last time she allowed herself to play. Having fun had become alien to me.

The next time I sat down to write, I skipped powering up the laptop and grabbed a sheet of black printer paper instead. I pulled Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping with the Dictionary from my bookshelf and found her “Jinglejangle” poem, where she leans heavily into wordplay and word association. I tasked myself with writing something similar. I set out to write a list (the word “poem” felt too serious still) that toyed with sound and made associative leaps. I wrote in pen so I wouldn’t be tempted to erase, so that I would be forced to let my impulses lead me to wherever this list wanted to go. I set a time for five minutes and wrote clean past it for fifteen. I filled the whole page. I knocked the language loose.

From that exercise I culled a new poem. Within days, I was back to collecting notes for poems in my phone, tapping out quick lines and images on walks, in restaurants. Returning to playfulness had revived something that had been strangled out by the weeds of my exam year. About two weeks after that exercise, I bought myself a sketchbook with unlined paper to brainstorm and write in. I’m learning to lean into messiness, to accept the mistakes on the page as possibilities. I carry the sketchbook with me wherever I go, excited to play with language, excited about being excited to write poems again.