Assistant Editor Lily Meyer: I do not like the term—or, indeed, the concept—lifestyle, but I have always loved old lifestyle books. In childhood, I spent visits to my grandparents’ house delightedly rereading an ancient copy of Marjabelle Young Stewart and Ann Buchwald’s White Gloves and Party Manners, an etiquette manual for children that was released in 1965 but that struck me as approximately the same age as Earth itself. I was always swiping outdated self-help books off adults’ bookshelves or digging to the bottom of the stacks of travel magazines my grandmother never threw out. My fixation persists to this day. I love knowing how I would have been expected, or perhaps would have aspired, to conduct my life twenty or forty or sixty years ago. These days, I especially like to think about how I would have cooked.

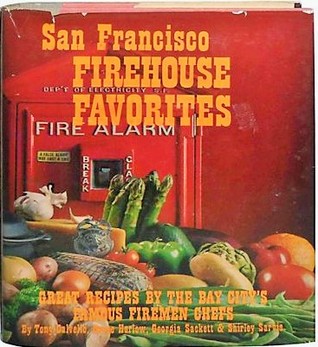

My favorite cookbook that I bought in 2021 came from an antique mall in Saint Paul, Minnesota. It has a glossy, crumbling cover featuring a red fire alarm and an abundant, plasticky-looking vegetable still life; the tan endpapers feature line drawings of pineapples, eggplants, artichokes, and peas popping out of their pods. It’s called San Francisco Firehouse Favorites, and was written—or, really, compiled—by Tony Calvello, Bruce Harlow, Georgia Sackett, and Shirley Sarvis, though the recipes inside belong not to them but to a host of firefighters. Like my old friend White Gloves and Party Manners, San Francisco Firehouse Favorites came out in 1965. A crucial difference, however, is that while I never once expected to follow Stewart and Buchwald’s advice, I have already cooked my way through a good portion of Firehouse Favorites. It hasn’t let me down yet.

Firehouse Favorites calls for far more processed food than the contemporary cookbooks to which I gravitate. It tends toward “mixed Italian dry herbs” instead of fresh thyme and oregano, garlic powder instead of real chopped-up cloves. Its contributors put green bell pepper in dishes to which I would never otherwise have dreamed of adding it. Cream is everywhere. So is Worcestershire sauce. These are old-school ingredients—and, indeed, old-school recipes. They are also delicious. I am thoroughly converted to Engine Co. 23’s Dust Bowl Soup, which features kidney beans, peas, potatoes, and ham hocks; I have discovered that I love chicken cacciatore. Fireman Ashley Hobson’s recipe for date pudding, which I personally consider more of a date cake, is the best dessert I’ve made all year.

Cooking fifty-five-year-old firehouse recipes reminds me that my moment in time shapes my palate, as it shapes so much else that seems intrinsic to me. Holiday cooking often does the same. My family is not given to innovation where celebration food is concerned. Our Thanksgiving stuffing, which is a perfect and iconic food, always has sweet Italian sausage and canned black olives, two ingredients my parents only use once a year. Our sweet potatoes always have marshmallows, but only on half the dish, since—truth be told—we all hate them. The marshmallows are a remnant of bygone sweet teeth and must be respected. Ditto the Hanukkah tradition, begun by my maternal grandfather, of drinking vodka on the rocks while frying latkes. Nobody in my household wants a glass of straight vodka, but my grandfather, a first-generation Russian Jew, liked it, and so, in honor of his taste, we pretend to be refreshed.

We all know that food tells us who we are. Old food—old dishes; old recipes; old cookbooks—tells us that we are not special. We’re products of habit and environment, of culture and exposure. We don’t invent our own lifestyles any more fully than we dictate the flow of our lives. I find this deeply reassuring to remember. I hope you, as you cook your traditional or nontraditional holiday meals, find it at least a little reassuring, too.