10 minutes read time

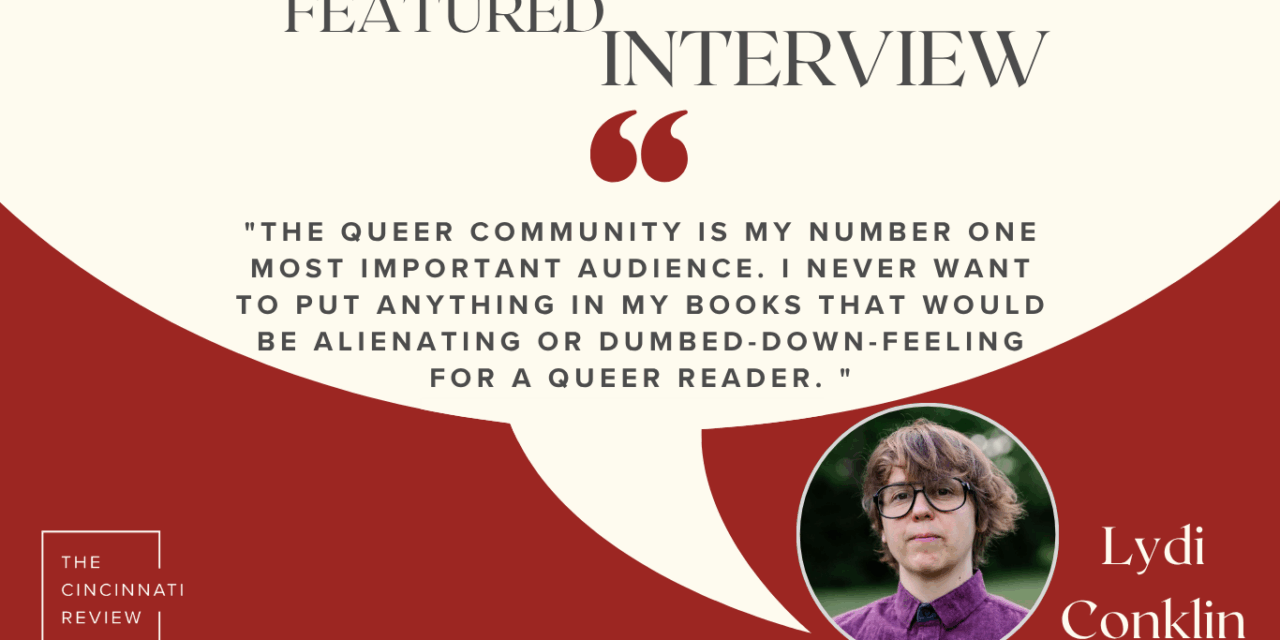

Lydi Conklin joined us this past spring for our Robert and Adele Schiff Fiction Festival, reading from their most recent books, the story collection Rainbow Rainbow and the novel Songs of No Provenance, both from Catapult Press. They corresponded this summer with former CR Assistant Editor Lily Davenport.

LD: One thing about Rainbow Rainbow that immediately delighted me was the approach you’ve taken to managing its audience(s). There’s humor—and pain—readily available here for everyone, but there are also so many moments that were uniquely funny and/or difficult for me, because they draw on, illuminate, or make affectionate light of queer experiences like mine. (I laughed too hard and knocked my coffee over when I hit the opening of “Cheerful Until Next Time.” I’m convinced that any queer person who’s been in humanities graduate school for too long has also attended this book club.) On the flip side: it can feel dangerous or fraught in our current political/cultural moment to write directly about tensions and issues within the queer community, or about queer people doing bad things, like the chat-room predator in “Ooh, the Suburbs.” Those choices offer the reader honesty and nuance, along with the in-jokes—but they can also feel loaded in scary ways, at least in my personal experience. Do you feel the shadows of multiple readerships while you’re writing and/or revising? How do you navigate the multiplicity of audience that queer stories inevitably carry with them?

LC: Thank you for such a thoughtful question and for thinking so carefully about these issues! The exact issues you mention are a big thing I think about when I write. My friend Jamel Brinkley put it so brilliantly, that his ideal audience is in the front row and he is speaking to them, but anyone can file in behind and hear him over their heads. And that’s how I feel, too. I’m glad you got the in-jokes related to the experiences, because the queer community is my number one most important audience. I never want to put anything in my books that would be alienating or dumbed-down-feeling for a queer reader. Like, hello, transgender means x. And what’s included in that mandate for me is making sure that I write about queer people with their full humanity. That they can have the dignity of being messy and acting badly and even being dicks if they want to. That’s part of what’s afforded by being human, and trying to sanitize a whole demographic for the sake of positive representation feels very dangerous to me, and dehumanizing. I also totally get the sentiment and the fear, especially in this hellacious climate we are in right now. I just don’t want the politics out there to take away our power to write whatever we want to write and whatever feels real and urgent to write about our communities. Some of the harder stories like you mentioned, like “Ooh the Suburbs,” was based on stuff that happened to me and I didn’t want to downplay or sugarcoat my experiences out of political fear. I actually think it’s politically crucial to allow queer characters to live the full spectrum of human experience and to allow queer writers to represent the nuance and complexity of their experiences. So queer writers shouldn’t be afraid! Honestly, I’m not that worried either, because I don’t think too many conservative people will pick up a book called Rainbow Rainbow that’s got a giant rainbow on the cover! But if they do, I hope they will be won over by the full humanity of the characters and will understand them as real people like themselves.

LD: I’m curious about the relationship between your comics and your fiction. Do they feel like separate practices to you, or are they more contiguous/in dialogue? Do you use one as a break from the other? How does your approach to craft, or to structure, change across media? I also notice that, at least in what’s featured online, you tend toward compressed forms in comics, and am curious to hear more about your process on that front.

LC: Yes they feel pretty separate to me, artistically, like I would never publish a book with both in it. However, they are definitely in dialogue. Like my comic “Lesbian Cattle Dogs” deals with the same questions of queer motherhood that my story “Laramie Time” deals with, just in very different ways. Like you say, the form is much more compressed in comics, the humor is more present, and there are speculative elements, like talking dogs. Or like, in the comic I’m working on now about trans identity, disembodied breasts. I think maybe it’s more natural to work in a more compressed form in comics because the process is so much more laborious. I always find it strange that comics take SO long to make—involving many steps in the process like writing, ruling pages, inking panels, loose pencils, tight pencils, inking, scanning and Photoshopping—yet are so quick to read, whereas prose involves less labor and fewer steps if not less time, but is slower to read.

LD: During the fiction festival panel here at UC, you spoke about your journey with interiority in fiction. I felt very close, in emotional terms, to the central characters in Rainbow Rainbow—even, and especially, when that was uncomfortable, because they were making terrible decisions—so I’d love to hear in more detail about your writing and revising processes in this regard. For so many of these characters, my understanding of their inner lives and my discomfort in sitting with them grew in proportion to one another; I cared about them, I knew things were going to turn out badly, and I couldn’t stop myself from sticking around to see it happen. How do you handle that balance: showing us so much of a person that it’s almost unbearable, keeping us hooked into their psyche from beginning to end?

LC: Ooh thank you that is such a compliment! The balance of interiority has been an intense journey for me. I think part of that journey has to do with being very disassociated from my body and my feelings. Because of that, and because I’m such a nerd student trying to be perfect all the time, I obsessively followed the directive “show don’t tell” in my early work, and my characters had almost no interiority. You can see shadows of that time in stories in the collection like “Pioneer” or “Ooh the Suburbs,” because that technique worked in stories about childhood, since children are often disconnected from their interiority in certain ways. Then for a while, like with the first novel I spent years on (and threw out), I had too much interiority to the point where the novel was completely claustrophobic and you couldn’t even tell what room the characters were in. I hopefully have by now found a better balance. “Laramie Time” was a story where I really tried to work out the balance I wanted. In that story, I wanted all of the tense moments and plot points to occur in Leigh’s mind, basically, and to still feel as propulsive as I could make them. As to your other question, to me nuanced and complicated characters are the most interesting to watch act on the page. If a character is too good and kind, and they don’t have complexities under the surface, my interest will wane. Because most of us act kindly in daily life, so it’s more interesting to see how someone who’s a bit more feral or spiky or brave will act.

LD: While all the stories in Rainbow Rainbow feel rooted in highly particularized times and places, “Pink Knives” stands out to me as the most specific of them all. It’s set in the San Francisco of 2020, post-lockdown and pre-vaccine; much of the piece’s tension stems from the omnipresent will I catch it, have I already caught it undercurrent of the early pandemic, which pulses, ever-present, alongside the story’s relational conflict. Do you find that setting gives rise to character and conflict, when you’re drafting a story (or even just considering it)? Did it require a different approach to write into a lockdown setting, as opposed to some of the more temporally distant stories, such as those set in nineties suburbia?

LC: That’s a great question! Yes, I definitely think that setting completely informs how characters act and what they do. Especially with queer characters. One of the stories takes place in Krakow as fascism was rising in 2018, another takes place in Laramie, WY, which is haunted by its history of violence against queer people. Queer characters will behave very differently in each of those settings, as well as in Clinton-era 90s New England. Those ways may be in some ways more subtle than in the COVID story, because behavioral choices were so urgent and confusing in that time. I was really interested in how queer, poly relationships were badly damaged by that time, by the threat of disease but also by shame and social pressure, so that’s what I wanted to write about. It was actually, like you say, a harder time and place to write about than any of the other stories and that’s because it was hard to figure out how to make the story different. Many people have many similar experiences in that time, and I don’t think many people would want to read about those experiences, which were boring and painful and traumatic. So I had to find a way to make the material my own.

LD: Your debut novel, Songs of No Provenance, is out in June—congratulations! Please tell us anything you’d like to share about the book, how you see it in connection or conversation with Rainbow Rainbow, or what you’re most excited about as your novel enters the world.

LC: Thank you so much, Lily! So the book is about a feral musician who commits a terrible act onstage and must flee New York to escape the impending internet storm. It’s in conversation with Rainbow Rainbow in that it also explores liminal queer identities and less-explored facets of queerness such as queerbaiting and romantic friendship. It also delves into other issues that I didn’t get to in Rainbow Rainbow, such as the difficulties around toxic fame and ethical artmaking. I’m excited for it to be out in the world, and I’m excited for my side project, where eight amazing musicians have interpreted songs from the book that I’m releasing, one per week, on my Instagram.

Lydi Conklin’s story collection, Rainbow Rainbow, was longlisted for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Award and The Story Prize. Their novel, Songs of No Provenance, was released in June 2025 from Catapult in the US and Vintage in the UK, and is currently longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. Conklin has received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award, a Creative Writing Fulbright in Poland, and a grant from the Elizabeth George Foundation. They’ve served as the Helen Zell Visiting Professor at the University of Michigan and are now an Assistant Professor of Fiction at Vanderbilt University.