Web and Media Editor Bess Winter: If you grew up in the era when cable was king, maybe you have fleeting memories of that weird local cable access show that used to come on late at night and, in its bizarreness, was life-affirming? Today Shane Joaquin Jimenez, whose story “Extinction Studies” appears in Issue 22.1, shares a bit about his favorite such show. We’re particularly excited that Count Cool Rider himself has given us permission to share some of these images alongside Shane’s essay.

Love at First Fright: A Late Night Watchlist

Another Saturday night in the worst city on Earth.

I’m fifteen years old. Two years stuck in Vegas after arriving one boiling afternoon in a bench-seat U-Haul, running with my mom and brother from one damn problem after another.

Outside my window, miles away, the Strip burns like some radioactive Pleasure Island in the desert. But I can close the blinds on the neon. And in the dark of my bedroom there’s the warm cathode ray glow of the TV. It’s time for Saturday Fright at the Movies.

Coast to coast, the airwaves used to be haunted by the late-night spooky intonations of B-movie horror TV hosts. But there was only one Count Cool Rider.

The host of Saturday Fright at the Movies, the Count was a glam-metal Dracula crossed with jumpsuit-era Elvis—yet all Vegas. Each week at 10 p.m. on Channel 33, for the entirety of Bill Clinton’s time in office, he rose from a coffin and stood in his dark soundstage lair, flanked by Spirit Halloween cobwebs and burning candelabras, and cut lounge-lizard one-liners about straight-to-video horror and sci-fi schlock.

It’s 1996 again. Conjuring his best Bela Lugosi, the Count looks into the camera and tells me he’s glad I joined him, so close to the witching hour, with all the fellow ghouls and undead. Here’s what we watch.

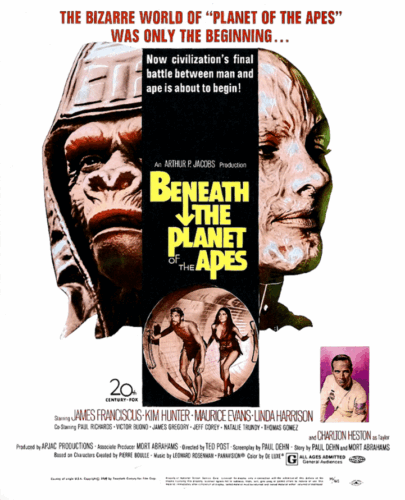

Beneath the Planet of the Apes

Out of all the ephemera (movies, TV shows, cartoons, lunch boxes) following the original Planet of the Apes, only this first sequel meets—maybe even exceeds—the sheer existential terror of the first film from 1968.

As I say in “Extinction Studies”: “In the year 3955 AD, under the surface of the planet lived the mutated remnants of humanity, made alien and unknowable by the future. The near annihilation of the Earth had not delivered the species to their extinction. Instead, the last humans had adapted to the new, strange, horrible world. They lived in a vast underground bunker and worshipped their god, the vengeful Alpha-Omega Bomb—a nuclear device set upon an altar of stone.”

Many years later, I’m reminded of the unnerving alienness of this far-flung vision when I read Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future, Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 “future history” sci-fi novel that tells the story of humanity across millions of years: “Earlier human species had not needed to trouble about mind’s ultimate fate; [. . .] now the life of the race itself was seen to be a mere instant between the endless void of the past and the endless void of the future.”

Godzilla vs. Megalon

Most of Saturday Fright at the Movies’ ten-year program schedule is lost to the void, but the archive of the Count’s glorious website confirms this Toho classic played on January 25, 1997. Underground nuclear tests send shock waves through a hidden undersea civilization, who in retaliation send their cockroach god Megalon aboveground to destroy the surface-dwellers.

As a kid, I was fascinated by the idea of hidden worlds, strange and forgotten, locked away within our own. At fifteen, I dreamed of escape, freedom, crossing a portal into a life worth living. In reruns of Duck Tales, I saw Scrooge McDuck and Launchpad McQuack find a lost city of diamonds at the center of the earth. Later, reading about bizarre hollow Earth theories of the nineteenth century, I came across the claim that we live on the outside surface of a hollow earth, which could be entered through ice portals in the Arctic and Antarctic. John Quincy Adams approved an expedition to discover the North Pole entrance into the hollow Earth, but Andrew Jackson stopped the expedition when he took office. He believed in a flat Earth.

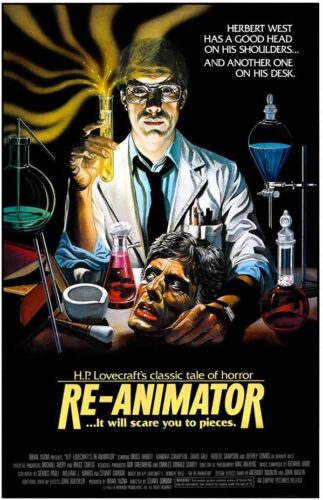

Re-Animator

The Count played this one on February 1, 1997. A ghoulish medical student revivifies the dead with a special serum, to predictable practical-effects grotesquerie.

In the mid ’90s I was on the cusp of discovering Jorge Luis Borges, who would change my life. In “The Immortal,” Borges writes: “To be immortal is commonplace; except for man, all creatures are immortal, for they are ignorant of death; what is divine, terrible, incomprehensible, is to know that one is immortal. I have noted that, in spite of religions, this conviction is very rare. Israelites, Christians and Muslims profess immortality, but the veneration they render this world proves they believe only in it, since they destine all other worlds, in infinite number, to be its reward or punishment.”

The Monster Club

This anthology film, based on the works of British horror writer R. Chetwynd-Hayes, features Vincent Price’s vampiric Erasmus introducing (with all of Price’s characteristic oozy charm) human John Carradine’s Chetwynd-Hayes to the titular Monster Club (check out this still at IMDB). Although the frame story looks like it was filmed in a single evening, with the worst store-bought monster masks 1981 had to offer, the final short has stayed with me for all the decades since I caught it one dark night on Saturday Fright at the Movies.

In “The Ghouls,” a horror movie director scouting isolated locations for his struggling film drives down a foggy lane and discovers a premodern village, locked away from time and overrun by sunken-eyed ghouls who obtain their clothes and food from miraculous boxes they dig up out of the ground . . . from the local graveyard.

“My mother,” says one human-born ghoul, “when I born, she be put into box. Then dug up for great eating!”

The director manages to flee and escape the village. But on the other side of the fog he finds . . . well, you’ll just have to see for yourself.

For me, raised on a diet of ’80s Hollywood and comic books, the fatalism of “The Ghouls” was a revelation. It said: Struggle all you like, kid. No one gets out alive.

Shane Joaquin Jimenez is the author of the feminist thriller novel Bondage (Close to the Bone, 2024). He holds an MFA from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. Originally from Las Vegas, where he faithfully watched Count Cool Rider every Saturday night, he now lives in Victoria, British Columbia.