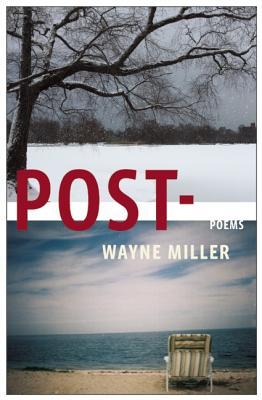

In his latest collection, Post- (Milkweed Editions), contributor Wayne Miller (6.2, 11.2) presents poems whose guiding poetic sensibility is able to navigate the terrains of memory and day-to-day life and mine them for what they have to say about personal and social life. “The Debt” opens this work by presenting variations on the title’s concept:

In his latest collection, Post- (Milkweed Editions), contributor Wayne Miller (6.2, 11.2) presents poems whose guiding poetic sensibility is able to navigate the terrains of memory and day-to-day life and mine them for what they have to say about personal and social life. “The Debt” opens this work by presenting variations on the title’s concept:

He entered through the doorway of his debt.

Workmen followed, bringing box after box

until everything he’d gather in his life

inhabited his debt. He opened the sliding door to the yard—

a breeze blew through the spaces of his debt,

blew the bills from the table onto the floor.

One can see how financial concerns impose themselves on life. Debt is the house lived in as much as a concept. What makes this poem such an effective opening piece is how it brings together a number of the collection’s themes, namely the way such intangible facts—in this case, debt and laws—affect our tangible lives.

The law theme is again explored in “The People’s History,” which creates a narrative around “the People,” and follows them as they comprise both a group of chanting protesters on a city street and a group policing them:

we, the People, will not be denied.

Then the People

descended upon the People, swinging hardwood batons

heavy with the weight of the People’s intent.

The narrative method here is compelling on two levels: 1) The use of “the People” for both sides makes the intangible nature of rhetoric and law transparent, which in turn makes the tangible effects on human action and experience all the more vivid; and 2) Rather than dulling or deflating the intensity of the scene, the use of the phrase complicates the narrative further:

But the People had grown tired of the afternoon

and released dogs into the crowd, dogs

that could not tell the People from the People;

Subverting the implied idea of an impersonal collective, the phrase takes on, through the poem’s twists and turns, a personal, individualistic meaning. In doing so, the poem indirectly paints a contemporary scene that becomes a direct and compassionate critique.

The themes of debt and inheritance are also found in poems that deal with the nature of words themselves. In “On Language,” the reader is presented the following fabulistic conceit:

1

There were only certain stones

we could step on to cross the river.

2

The stones we could step on to cross the river

were not certain.

Further developing this conceit, the poet states that “the stones we stepped on/ dropped away behind us/ like the notes of a song.” The connotations of this premise are rich: A set of stones is language, the river is speech, and the other side of the river is meaning. Not only is the transient and harried nature of establishing meaning conveyed, but so is the “not certain” feeling of the human effort to communicate. And yet, the speaker’s fable is one of hope, which the urgency behind the midpoem statement—“Love, stay with me inside this syntax of the river”—makes evident.

The sequence of five poems titled “Post-Elegy” that are scattered throughout the collection present a confluence of debt/inheritance narratives. The first describes how “After the plane went down/ the cars sat for weeks in long-term parking.” The speaker’s journey to retrieve the dead person’s car becomes a process of growing awareness, culminating in the following observations as the speaker drives off:

. . . I realized

I was steering homeward

the down payment

of some house we might live in

for the rest of our lives.

The metaphor here makes grief a physical presence, the car suddenly a space where the memory of the dead person lives on.

In the world of Post-, we are left in such complicated afters: the after of accumulating debt; the after of having to distinguish “the People” from each other; the after of wanting stay inside “this syntax of the river.”

interview

JAA: What role do you feel the personal and the social have in your work as reflected in this collection?

WM: For some time I’ve been interested in complicating that personal-social dichotomy by considering how personal narratives bump up against larger historical moments and metanarratives. Thus, in Post- I’m often trying to entangle the personal and social—to juxtapose them or contextualize each inside the other.

WM: For some time I’ve been interested in complicating that personal-social dichotomy by considering how personal narratives bump up against larger historical moments and metanarratives. Thus, in Post- I’m often trying to entangle the personal and social—to juxtapose them or contextualize each inside the other.

For example, Post-’s opening poem, “The Debt,” depicts a father-son relationship while insistently pulling into the frame how middle-class American life is built structurally on debt. Similarly, “Consumers in Rowboat” presents a tug of war between a couple’s own perception of themselves as private, autonomous individuals and the larger economic perspective that they’re demographically trackable consumers. And throughout the book poems about parenthood and loss sit intentionally beside poems about sociopolitical conflict and violence.

I’ve long loved Donald Justice’s well-anthologized poem “Men at Forty,” which feels personal and distilled as the men move solitarily through their domestic spaces while considering their own aging. When, in the last line, Justice describes their houses as “mortgaged,” it felt to me like an almost shocking (and compelling!) breech of the poem’s private lyrical “purity.” That’s just one small example—but it’s the sort of complicating of lyrical isolation that I was reaching for when I was writing Post-.

*

Post- is available for purchase from Milkweed Editions.

To find out more about Wayne Miller’s work, check out his site.