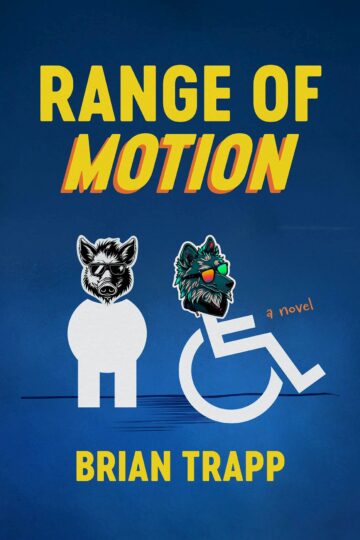

Finishing Sentences: An Interview with Brian Trapp about Humor, Disability, and Twinship in his debut novel Range of Motion

12 Minutes Read Time

Web and Media Editor Bess Winter: Last week we welcomed former CR editor Brian Trapp back to Cincinnati for the launch of his much-anticipated debut, Range of Motion. We’re delighted to share this interview between Brian and CR contributor Anya Groner.

In Brian Trapp’s debut novel, Range of Motion, the paths of twin brothers Sal and Michael Mitchell diverge at birth. A brain bleed leaves Sal with severe cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities. Michael is physically unscathed but struggles with survivor’s guilt. Sal’s parents are changed, too. His mother, Hannah, quits her job to become a full-time caretaker, while Sal’s father, Gabe, retreats into his work as a neuroscientist. With limited language and mobility, Sal negotiates the day-to-day conditions of his life with the tools available to him: physical resistance, a motorized wheelchair, and a computer capable of speaking prerecorded phrases. As a child, Michael understands what Sal means to communicate, but as he grows older, he begins to doubt his interpretations.

The novel is partly autobiographical. Brian’s own twin brother Danny, to whom he dedicates the book, also had cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities, which is perhaps why Trapp is able to portray the Mitchell family with such precision, tenderness, and humor. The book opens with Michael and Sal at a camp for disabled people, where they’re meant to enjoy a last week together before Michael goes off to college and Sal, although he doesn’t know it yet, goes to live at a facility. When Sal runs away from a camp pool party using his power chair, Michael must figure out what his brother really wants.

Spanning eighteen years, the novel probes the psychological, emotional, and physical depths of caregiving and the impossible task of navigating life in a society that has little interest in acknowledging or accommodating the needs of disabled people and their families. It’s also a comedic romp. (At one point, Michael uses Sal’s computer to insult his teacher with the prerecorded phrase, “Mrs. B, nobody gives a shit about your cat.”) The stakes for the Mitchell family are high, and the story Trapp tells about them is serious and seriously funny.

AG: Your novel is funny from the very first line: “It was late morning on their third day at Camp Cheerful, right before lunch, and it was unclear if Sal was having fun.” Humor gets the Mitchell family through difficult moments and propels the narration. What role do you see humor playing in your book? How do you use humor to push back against the discomfort many people have talking about disability?

BT: Humor serves as a counterweight to the stereotypical expectations people have about disability. We’re taught that disability is tragic, sad, and maybe inspiring. But comedy is the genre of survival. Life after a diagnosis doesn’t end. I think back to my book’s epigraph, taken from Djuna Barnes’ novel Nightwood: “There is more in sickness than the name of that sickness.” Comedy is the perfect lens to show us that “more.”

Sal is a comic character. He may have a feeding tube and the ability to only say 8 words—but he’s also not impressed with this place called “Camp Cheerful,” finds all the singing annoying, and is giving his brother shit. Michael is sort of a screw up with good intentions. Together, they have a playful give-each-other-crap relationship.

I gave Sal my twin brother’s comic spirit. If Danny wasn’t teasing us or smiling, we’d worry he was in pain or too tired. He was limited in what he could do or say, but he found creative ways to be funny and playful. Humor was an affirmation of his quality of life. The same goes for Sal.

For my other characters—Michael and his parents—I use humor to dispel the discomfort people might feel about disability. I’m trying to bring the reader into what it feels like to love and care for someone like Sal. In my house, we sang silly songs and bantered when we showered, dressed, or fed Danny. I wanted to reflect playful moments like those in the book. My characters are not sitting around mourning the fact that Sal has a disability, even if grief occasionally swims to the surface. People often said that to have a family member like my brother was “unimaginable.” Hopefully, I’m making that imaginable in a vivid and compelling way.

AG: Range of Motion is fiction, but like many debut novels, it draws heavily on your own experience. You’ve written stunning essays about your relationship with your twin. Why did you choose to write a novel and not a memoir?

BT: The central event of the novel—Sal escaping in his power chair from a camp luau onto a busy road—was something my twin brother never did. It was actually one of my other campers at the real Camp Cheerful, where Danny and I went for several years in high school. The camper reminded me so much of Danny except he could drive a power chair and had functional vision. His family visited him at camp and when they left, he fell into a deep depression. I took my eye off him for a few minutes at the camp pool party, and he escaped. He was rescued safely from the road and brought back to camp but the event affected me deeply. I didn’t know if he was trying to hurt himself or go after his family or play an epic prank.

The novel started as a way to write about that incident and the wonderful mad place that is Camp Cheerful. The escape pressed on the central question I had about the camper and about my own brother: What is he thinking? The novel became an answer to that question, which I backfilled with a lot of my own experiences growing up with Danny.

There is immense publishing industry pressure for disability stories to be told strictly as memoir. But I believe in the novel’s power to dramatize what it’s like to be in another person’s consciousness. With fiction, you can literalize a metaphor and go beyond the limits of realism. In my nonfiction, I’ve written: “It was like I knew what my brother was thinking.” Fiction let me erase the boundaries between reality and subjectivity, inside and outside, so that the character actually hears his brother’s speech as a secret language. That is closer to the emotional truth of my experience.

What is he thinking? The novel became an answer to that question, which I backfilled with a lot of my own experiences growing up with Danny.

AG: As an identical twin myself, I often find myself annoyed by how twins are portrayed in literature. The literary device of “twinning” opens up questions of identity and difference, but too often writers fail to consider what it feels like to be so connected to another person and simultaneously seen as only half of a unit. Did you have misunderstandings about twins that you wanted to set straight?

BT: Maybe the biggest misunderstanding is how it really feels to be a twin, especially of someone who has a significant mobility and communication disability. The philosopher Helen DeBres says that in Western culture, you are taught to think of people as discreet individuals, autonomous and self-reliant. Twins challenge that notion. Disabled people do, too. Both trouble the boundaries between minds and bodies.

People assumed that because my brother was severely disabled, we missed out on the usual twin experience. We went to separate schools. We didn’t share many friends. There were so many things I could do that he couldn’t. In the novel, Michael dreams of playing the “twin trick,” of trading places with Sal and seeing who notices. That stereotypical confusion of identity wasn’t possible for me and Danny or for my characters. But in other surprising ways, Danny and I blended our identities. My brother’s disabilities required us to be incredibly interdependent. I often had to be his hands, his legs, his voice. I felt most like myself when I was pushing his wheelchair or feeding him. I was finishing his sentences all the time, supplementing and translating his twelve words, vocal tone, and body language. It was not much of an exaggeration to depict twin telepathy in the novel. But I was interested in exploring the ethical limits too—how Michael might mistake his own thoughts and desires for Sal’s and how their twin unit could fracture.

AG: Class is a major theme in your book. Hannah, the mother, stays home to take care of Sal, which means the entire family relies on the father Gabe’s paycheck. As a scientist, he’s struggling to get a grant to fund his lab and then make a big discovery that will finance Sal’s care. What role does class play in this book and how does financial instability impact special needs families?

BT: In the recent PBS documentary Caregiving, Josh Carter of the Carter Center talks about how government-supported institutionalization was dismantled in the 60s and 70s. He says it wasn’t replaced with “any government supported care. It was replaced by family members.” That’s the world Sal is born into, and my brother was born into, and it informs a lot of how class is depicted in the book.

Sal’s parents, Hannah and Gabe, are middle class strivers who believe in the American dream, but from the moment Sal is born, their hopes are channeled into giving Sal the best possible life. Like many mothers of medically complex children, Hannah quits her job to care for her son. While the family is privileged to be able to rely on Gabe’s single income, their finances are precarious. They make too much money to qualify for government assistance but not enough to afford everything that Sal needs. Each decision they make is meant to give their vulnerable child a better life in a world where support is unequally distributed.

In the U.S., financial instability is baked into the experience of having a disabled child. We’re tricked into thinking of disability as a “burden” rather than an inevitable fact of life. One of the most depressing aspects of researching the novel is realizing things have gotten worse since 2002, when the novel ends.

AG: As a kid, Michael “translates” for Sal. As a teenager, Michael records phrases into a computer called a “Whisper Wolf” that can talk for Sal, and is accused of projecting his own thoughts onto Sal. Your novel asks readers to consider how deeply anyone can know another person–including your own twin. Did you have a sense as you were writing whether or not Michael really could understand Sal?

BT: For the integrity of my characters, I had to believe in both possibilities: that Michael could really hear Sal and that he could also be making it up. When I was first drafting the novel, I was terrified when Sal started speaking in Michael’s point-of-view. It was literally impossible but incredibly compelling. I consider myself a realist writer. I don’t love fantasy or magical realism. I thought: Can I actually pull this off?

The escape at the camp is a heightened moment of doubt for Michael, so it made sense to begin their relationship in a state of absolute confidence. As a child, Michael doesn’t just think he knows what his brother is thinking—he can literally hear Sal. This causes friction in the family. Gabe is suspicious when Michael translates for his brother and Hannah is mostly sympathetic.

As he grows, Michael slowly loses the ability to hear his brother, first in dialogue and then as a voice in his head. You can reduce it to human psychology—a little boy who has difficulty discerning reality from imagination—but I wanted the story to keep open the more extraordinary possibility: that these twins have a telepathic connection beyond explanation.

AG: How did your own understanding of disability and caregiving evolve as you wrote this book?

BT: When I began the book, I thought of disability as something that resided in my brother’s body and mind. I thought of care as something that we give him. But through the process of paying such close attention to my memories and my characters, I began to think about disability and caregiving as a culture too. With my brother, I think of how we were always interpreting his speech and non-verbal communications and all the ways he invented to express himself. What is that other than a language? My brother didn’t just receive care—he negotiated it, making it easier or harder and giving it back. The joking I describe in the book was not just insular to my family but maybe reflect a wider type of humor employed by disabled people and their families. When you love someone who is not valued by the dominant culture, you need to construct an alternative value system. That’s culture, too. And in the novel, I think I’m dramatizing that culture even if it’s often difficult for the characters to sustain.