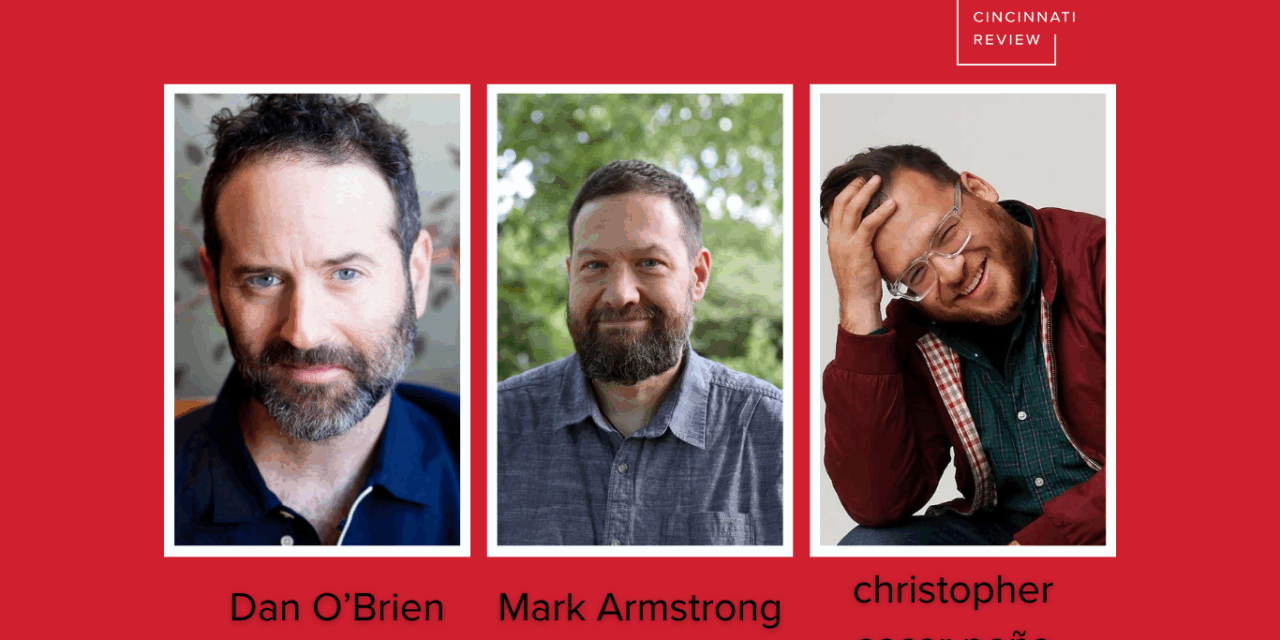

Drama Editor Brant Russell: We published Dan O’Brien’s Newtown in the Summer 2019 issue and chris peña’s The Strangers in the Winter 2019 issue. They’re very different plays and Dan and chris are very different writers. Their nontheatrical writing explores different modalities (chris works in television; Dan is a poet and essayist). But they have both written plays that we love, and their work (as you’ll see) shares an affinity for language. Please enjoy this interview, in which chris and Dan talk about what artistic passions they have in common.

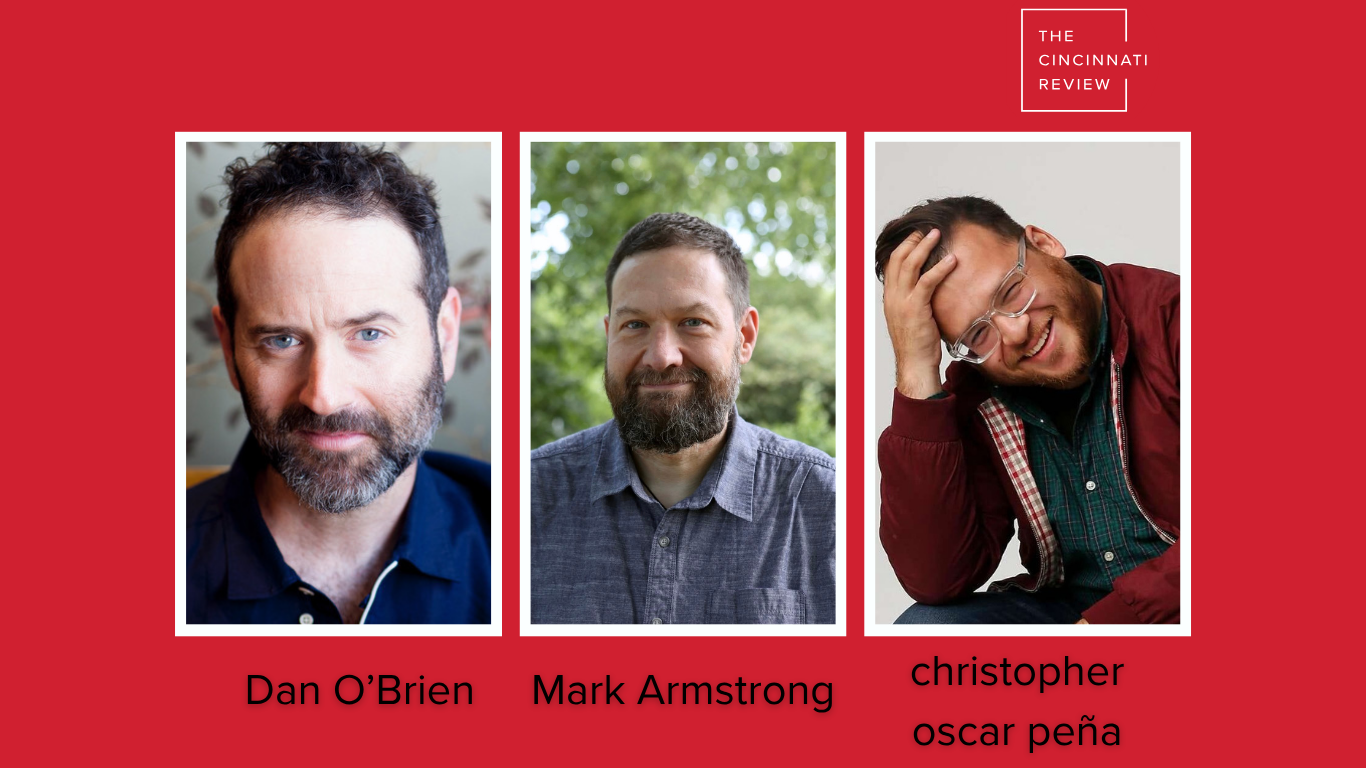

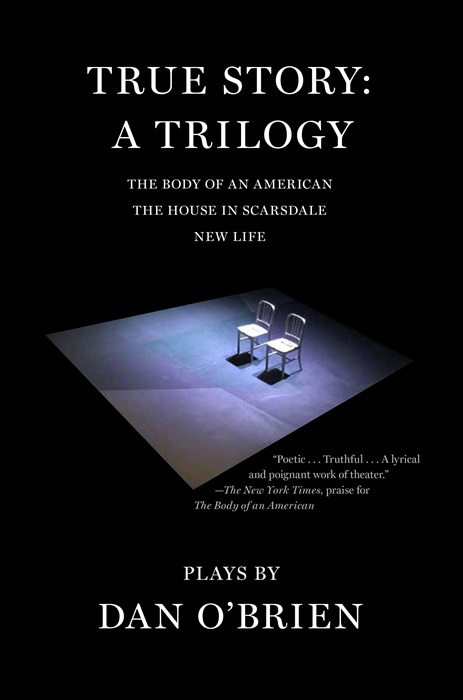

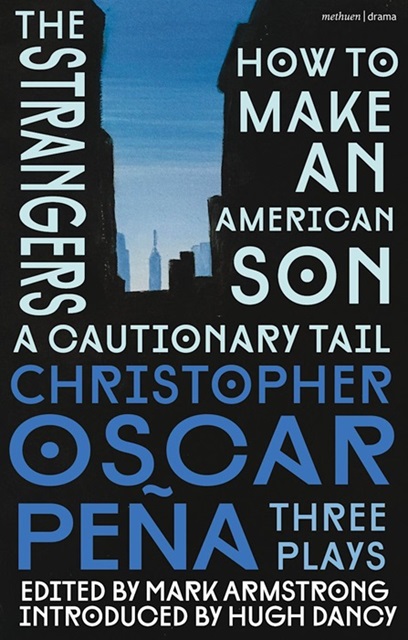

The following interview was conducted via Zoom by director and producer Mark Armstrong, on the occasion of the publication of christopher oscar peña’s Three Plays (Bloomsbury, 2024) and Dan O’Brien’s True Story: A Trilogy (Dalkey Archive Press, 2024). The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

MARK: Sometimes people ask me how I choose the plays I want to direct. And I always have the same answer: I like plays where, after reading the script, I feel like I know the person who wrote it. And that’s how I feel about both of you. And of course now I do know you! Because I’ve directed your plays, etc. But how aware of each other’s work have you both been?

DAN: The first time I was introduced to your work, chris, was at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference.

CHRIS: In 2011. You were co-leading the playwriting workshop with Beth Henley.

DAN: I remember when I met you I was so impressed by your talent and energy and ambition. Your use of language on the page, of course, but also how the language sounded in my mind—poetic and lyrical in a powerfully dramatic way that I connected with and identified with immediately.

CHRIS: I love that. I love that because you’re actually a poet!

DAN: So it was exciting to read Three Plays over the last few days and remember my early impressions of you and your work. And to see your evolution since.

CHRIS: I read [your play] The Cherry Sisters Revisited before I went to Sewanee. And then several years later I remember seeing The Body of an American at The Cherry Lane Theatre in New York. I remember thinking, This is a completely different thing than The Cherry Sisters, which was theatrical and fun, about women in vaudeville. But then you went to this other place with The Body of an American, a play about PTSD and war reporting. It felt like you’d completely reinvented yourself. It was exciting.

So what’s interesting about reading the three plays in True Story has been like, Oh, he’s morphed into this thing, and he’s going to live there for however long. And it’s fascinating because I find myself feeling that way every time I write a new play. I’m like, am I still in the world of my voice, or am I going somewhere else?

MARK: Do you both feel a need to change with every play?

DAN: I don’t feel like I have much control. I try to leave myself open to changing, but any kind of creative evolution usually happens when my life is changing drastically. The three plays in True Story are the result of my childhood trauma coming back to haunt me when my parents disowned me in my thirties. Which was both a liberating and a profoundly disorienting experience.

That’s where this connection to the combat journalist Paul Watson came from. I was trying to explore post-traumatic stress disorder—his and mine—in a theatricalized way, so that an audience might experience some of that disorder. The second play in the trilogy, The House in Scarsdale, deals directly with my family story. And the third play, New Life, turned into an exploration of the trauma of back-to-back cancer diagnoses for my wife and me, and coupling that with Paul Watson’s desire to leave the trauma of war reporting for what he hoped could be the happy ending of a career in showbiz. This is why that play slowly transforms into something close to comedy.

CHRIS: I was on the ride of this heavy, poetic, serious—you know, dark thing with the first two plays. Then when I got to New Life—I knew it was a conclusion, so I was wondering how this was all going to end. So when you introduce, like, the TV side, I just started laughing. Because as somebody who works in TV, I know how stupid it is. And literally I was like—I would never have guessed that these plays were going to end this way. He took all this war trauma and family trauma and turned it into a French absurdist comedy about TV!

DAN: Well, I’m glad it came across that way. It’s tricky. I told Paul, when he had this idea of pitching a “prestige” cable TV drama about journalists covering the war in Syria, that (A) I didn’t think we’d be able to sell it. I’m not a TV writer, and neither is he, so it’d be tough. (B) I would happily collaborate on the pitch, and I’d do my best to sell it. But (C) I wanted to write poems and a play about the whole process.

CHRIS: One of the great things about the trilogy is we all have our own lives, right? And just because I don’t have experience in war-torn countries or a family that’s disowned me—it doesn’t mean my own pain doesn’t matter. This is something I think everyone goes through in therapy. Like, Oh, I can’t complain about whatever, my pain over my heartbreak, because I have a TV career. So it was so fascinating to me that Paul Watson is like this cowboy, right? He doesn’t give a fuck. He’s the one who actually has the most psychotic life—he’s choosing to put himself there.

But the trauma of being a TV writer, the trauma of being a playwright, the trauma of being a journalist, the trauma of whatever—it’s all the same. We all have what is ours. And I thought that was lovely, that you figured out how to honor everybody’s various degrees of pain. But also to show that all pain is valuable. And so is all the joy.

DAN: That’s where the impulse originally came from—to have a character named “Dan” on stage. The impulse being, Okay, if I’m gonna write about Paul, I don’t want to only write about him and characters like him. If I only told his story then it might allow the audience to regard him as something of an other, and view the people he interacts with in war zones as others. There’d be no empathy. If “Dan” the playwright in the play could act like an intermediary, somebody who has the kind of trauma that’s similar to what many of us have, then the play could be more useful.

CHRIS: As different as our trilogies are, this is one of the things that I feel excited about, just kind of connecting about the autobiographical in our plays. I was shocked at how aggressively you put yourself on the page. The sort of stripping back, the honesty. And I really responded to that, because when I go back and look at my plays, what I’ve noticed in my evolution is that the plays get more and more autobiographical over time. So like, what is that? Is it just that I don’t want to hide anymore? Is it that I’m getting older, so it’s important for me to be honest about what I care about? Part of me misses the whimsical theatricality of my earlier plays. But I just want to be more honest now, you know?

MARK: I observed the same thing in your work, Dan: the shift from third person to first person, so to speak. And in your work too, chris. Which is the reverse of how it usually goes. When playwrights first write plays, they’re often a character, or the main character. With you both, in what I consider your mature work, the two of you go deeper into yourselves.

CHRIS: I remember when I was much younger being in love with, like, all these fucking weirdo playwrights. And then as I got older I was like, Oh, I guess these same playwrights sold out for their off-Broadway debuts. Their plays were losing that weird theatrical whimsy. They were writing naturalism because they needed to pay the bills. And I get it. But when I was writing How to Make An American Son, I felt like, Oh, this isn’t about selling out. It’s about trying to reach people in a way that’s clearer. It’s about getting to the truth. Telling the truth in a way that feels beautiful because it’s scary and vulnerable but honest, and really it’s nice to be like, Oh, right, I’m not the only fucked-up person in the world.

DAN: That’s what we’re all doing, right? Writing to figure out our lives at the same time that we’re living it? And my take—not an original take—is that trauma shatters your sense of who you are. Shatters and remakes you, if you’re lucky. So in the wake of trauma, whether that’s months or years later, there’s going to be a period of asking yourself, “Who am I now?” And for me that’s the fundamental question of theater.

CHRIS: American Son is me. Like 70 percent of that character is me, and most of that happened to me. That play was the first time anybody who knew me knew it was me. American Son really fucked with me, because I wrote the thing that I thought was gonna, like, make people understand me. And I thought people would be like, “We finally get you.” And instead, every night, four hundred people would clap at my demise. They wouldn’t know that I was in the audience. So I would hear them talk about me. I would cry every day. I remember the cast, who are all friends, were like, “Are you okay?” And I’m like, “I don’t know what’s happening. I don’t ever cry.”

And then my therapist very smartly said: “chris, when you first started therapy you said that you were very put-together because you put all your pain in your plays, and then the pain goes away.” He’s like, “What do you think it felt like to sit for two months in rehearsals with people you love and trust, talking about your trauma, and then having four hundred people watch that and laugh at you every night?” I was like, “You’re right.”

DAN: With the plays in True Story many people have said to me “Oh, you’re so brave. How brave of you to write this.” They mean it as a compliment, usually. On one hand I get it, because I am making myself more vulnerable than if I wrote something that’s not so nakedly my story. On the other hand I don’t get it, this “bravery” idea. Maybe it’s like a mental deficiency in me or I’m simply a narcissist, but I suppose I’ve grown used to this idea of “Dan” as a character. He’s not me. We’re different, no matter how accurately I try to write him. I mean, I’m not brave. I can’t even bear to read reviews—mine or anybody else’s!

CHRIS: When we were making the last three plays, I cared so much to the point where I would get sick. I’d never gotten sick making a play. The last three openings I had that were part of this chris peña series, I got very sick the week of tech. The first time I basically had like a three-day hallucinatory fever, and I made it just in time for opening. The second, I lost my voice for ten days. And the third, my back was thrown out. I went to the doctor and they were like, “You’re making yourself sick because you’re so anxious about people seeing these plays.” And, like: of course!

DAN: The plays I like, like chris’s plays, and the kind of plays I try to write, make people feel contradictory things. With my memoir play The House in Scarsdale, many people have had a very complicated response to it, in terms of their own families, and in terms of their own feelings of family shame. At the same time people have approached me after a reading or a performance, and three minutes into the conversation they’re telling me their family’s deepest, darkest secrets. And I happen to think that’s wonderful. It’s what storytelling’s for. It’s what art and especially the theatre is for. Connecting strangers. Getting rid of the shame and solitude around trauma and pain.

But the audience response has been complicated with The House in Scarsdale because it involves the airing of a family’s dirty laundry—which is a taboo for so many. It’s one of the Ten Commandments, right? Honor your father and your mother. I think that particular commandment deserves an asterisk: If they’re abusive, maybe not so much.

CHRIS: I have kind of the opposite version of Dan, which is that my parents have really taken care of me, so I always hesitate to write my pain because no matter how I write it, even if I’m like, “It’s not your fault,” they will always take that responsibility on. Right? But at the same time we’re both still thinking about it: Are we hurting people just by trying to figure ourselves out? So that’s been the hardest, my parents going to my openings because they want to be supportive. I’m putting myself out there, but at the same time I’m putting them out there too, you know?

DAN: That’s very complicated. Very difficult.

CHRIS: If our job is to tell the truth, is it possible to tell the truth without collateral damage? Which is such a terrible phrase. I don’t think any of us sets out to weaponize our work. Your plays are filled with so much pain, Dan, but really they’re filled with, like, somebody trying to figure out their place in the world. And I feel like every play for me is about “How do I love other people?” But at the same time, in the process of creating those narratives, there’s such potential to hurt the people that I’m trying to protect.

MARK: How do you navigate that?

CHRIS: This last play that I wrote was a coming-home-broken play, in the end. I literally rewrote the play every single day in rehearsals and tech until opening night, because it wasn’t working. But I realized that my big fear was that it was gonna break my mom’s heart, and then I kind of figured out, Oh, the play is not about me ending up alone. The play is about me coming home to my mom to say, “You’re the one who’s taken care of me.” So the minute I put that realization in the play, I knew there was going to be an hour-and-a-half of stuff that she had to deal with. But at the end, she felt like, Oh, my son loves me, and I feel seen, and I love him.

So that’s how I’ve handled responsibility. But part of me is sometimes like, am I being less truthful because I’m trying to be protective? It’s easy for people to view writers as narcissists, or like we’re unaware or uncaring, but people don’t realize how much is in our brains about carrying that burden of taking care of the people we write about.

MARK: I think both of you are the hardest on yourselves, both in your life and in your work, you know?

DAN: Well, that’s only fair, right?

Mark Armstrong is a Brooklyn-based theater director and the artistic director of The 24 Hour Plays. His production of Eric Bogosian’s Drinking in America featuring Andre Royo (a New York Times Critic’s Pick) enjoyed an extended run at Audible’s Minetta Lane Theatre. His collaborations with playwrights include productions with Dan O’Brien, Emily Mann, Christopher Shinn, and many others.

Dan O’Brien is a playwright, poet, and nonfiction writer whose recognition for playwriting includes a Guggenheim Fellowship and two PEN America Awards, and for poetry the Fenton Aldeburgh Prize in the UK. True Story: A Trilogy of his plays was published in 2024 by Dalkey Archive Press. He lives in Los Angeles.

christopher oscar peña works in film, tv, and theatre. A two-time Sundance Fellow, he has been the artistic associate at Arizona Theatre Company, an alumni of New Dramatists, a recipient of the Latino Playwrights award from the Kennedy Center, and a Van Lier New Voices Fellow at the Lark. He’s a New York Theatre Workshop Usual Suspect and currently sits on the boards of The 24 Hour Plays in New York and Diversionary Theatre in San Diego.