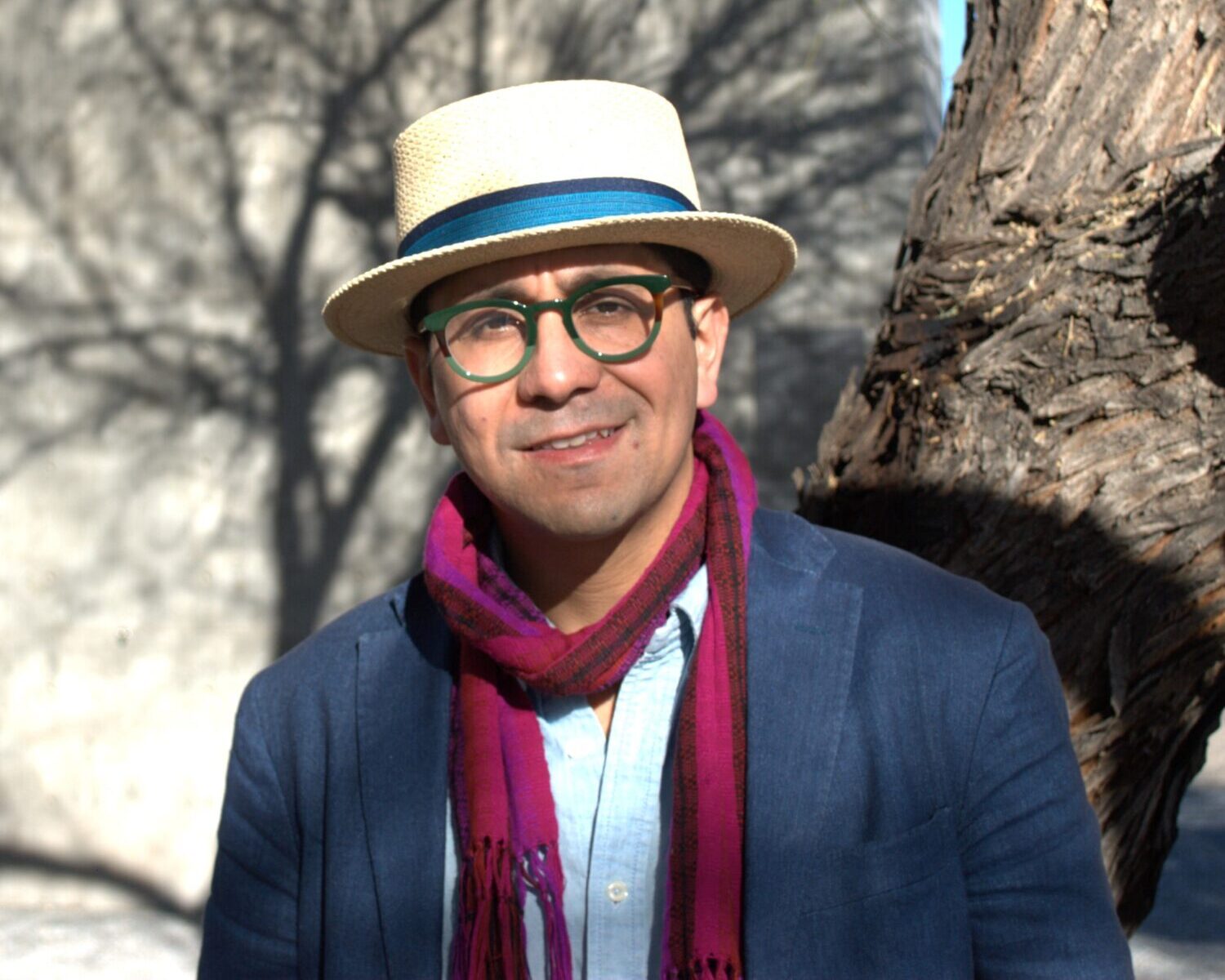

Associate Editor Andy Sia: Edgar Garcia joins us this week at the University of Cincinnati for the Visiting Writers Series. I reached out via email and had the pleasure of learning more about his process and poetics.

I would love to start with your thoughts on research. In Skins of Columbus, you take Columbus’s diary as the starting point for a poetic experiment. For three months you read a journal entry before sleep, then recorded and translated your dreams to examine the “inner workings of the colonial myth” and “entanglements warped in a historical structure.” The resulting book is a rich tapestry, wherein you weave poetry, prose, and visual forms, as well as various modalities: myth, dream, theory, biography. I’m struck, incidentally, by your endnotes, which evince the care in your research and writing process. How do research and creative work intersect for you? How do you pull the threads of research together toward a project like a book?

I cannot write without research and I cannot research without the writing in front of me, pulling me forward, the entire way through. I wrote Skins of Columbus (a collection of poems and mini essays) at the same time that I was writing Signs of the Americas (a scholarly monography). At the outset, these projects seemed simultaneously to be pulling me in two directions and bleeding into each other. It wasn’t until I came to be able to theorize those scissoring and spillage effects that I was able to complete either book. That is to say, I learned how to even think about poetry from my research and was only able to properly conceptualize what my research was for from my poetry. These doublings have to do with the kinds of things I was picking up on in indigenous poetics, especially Mesoamerican poetics, which have to do with the value of non-synthesizing but mutually animating doubles and opposites, chiasmi of sorts, that helped me open up my reading and my writing (my research and my poetry) to their own kinds of mutually animating positions.

Collaboration seems like an integral part of your work. Since 2012, you have collaborated on a blog with the poet and writer Jose-Luis Moctezuma. You talk about this collaborative project in Skins of Columbus as “a type of ritual collecting, documenting the many traces of self-splitting, cosmic pairing, and metamorphosis in the Americas.” I’m thinking here too of your collaboration with the visual artist Eamon Ore-Giron, in Infinite Regress. I love sitting with the correspondences between Ore-Giron’s geometric, cosmological paintings and your poetry, which reflects on topology, feeling, time. What have you learned from your creative collaborations?

I have had to learn to prize the difficulty of collaboration. People don’t agree, especially when artistic visions intersect, conflict, and pull in different directions. It is not easy to work out all those differences. But it also does not matter much for the work of art if it doesn’t have artistic tension. So as I’ve worked through so many collaborations—flailing through so many moments, flying into various successful objects—I’ve learned to listen. And listening as an art has been very important for my work even when it is not in apparent collaboration. For instance, working with a book like the Popol Vuh (a K’iche’ Maya story of creation, as I do in my book of essays, Emergency) or with the Cantares Mexicanos (a Nahuatl-language collection of early colonial songs, as I do in my collection of poems and essays, Cantares, forthcoming with Wesleyan University Press), I have had to open my ears to the actual voices in these works, which is to say I have had to open my mind to what they are saying to me here and now. There is something ritualistic about this process of listening but its ritual is more quotidian than anything else: What, I ask myself, are these works trying to show me about my place here and now in relation to the histories of the Americas precolonial, colonial, and contemporary; what are they saying and how does that split me, pair me, or transform me in a collaborative and critically creative way?

You are a teacher in addition to being a writer. What advice do you have for writers, particularly young or emerging writers?

History must stand in front of the writer, staring them into such anxiety that they feel the nerves of history running under their muscles and over their bones. That is, I think it is important for writers to write through the distances and alienations of historical crises. One thing that I have learned from students is that sometimes they are wary about touching history, especially hard histories, because they don’t feel confident that it is their right to do that. Of course, these things must be treated with care and respect, especially if you believe—as I do—that the ancestors are with us, but for that very same reason, I think we have to be in dialogue with them even when all they have to offer us are tough silences. Those silences are significant because they are often enforced silences—silences produced by the violences of history—so even if the task is to leap across the aporia or the big vacuous gap, if that is the task that sits before you, then that is your task. I have been asked, regarding my book Skins of Columbus (the strange psychic immersion in the dreamscape of the founding mythos of colonial history): Why would you do that? Why would you put yourself in that mental space for so many months to write that book? And of course I had terrible dreams in writing that book, recurring nightmares and troubling conflations of my dreaming and waking life. But I knew I just had to write that book; I knew all along, even if I didn’t quite know why. At one point I wrote an essay about the toxicity of paint and how painters poison themselves for their art, and in writing that essay I finally found the answer I was looking for myself. For my own particular case, I realized that the artist of the Americas must ingest the poison of colonial historicity and, compositionally blurring the distinction between historical worlds and physiological worlds, transform that poison into a kind of self-possession that is historical redemption. They must eat lead and sweat orichalcum; they must breathe pollution and speak poetry. It’s a tough lesson but a good one to hear: we must reckon with hard histories and make of such crisis tremendous efforts of creativity and world creation. Either it is underworlds all the way through or it is without its world thoroughly.

Edgar Garcia is a poet and scholar of the hemispheric cultures of the Americas. He is the author of Skins of Columbus: A Dream Ethnography (Fence Books, 2019); Signs of the Americas: A Poetics of Pictography, Hieroglyphs, and Khipu (University of Chicago Press, 2020); Infinite Regress (collaborative work with Eamon Ore-Giron, Bom Dia Books, 2021); and Emergency: Reading the Popol Vuh in a Time of Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2022). His collection of adaptations and translations of mid-sixteenth century Nahuatl-language songs, Cantares, is forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press in 2026; and a book about the baroque titled Caravaggio’s Americas is also in final stages of completion. Most recently he has been collaborating with the American Modern Opera Company on adaptations of these writings, which have performed at the Clark Art Institute, Peabody Essex Museum, and Lincoln Center. He is faculty in the departments of English and Creative Writing at the University of Chicago.