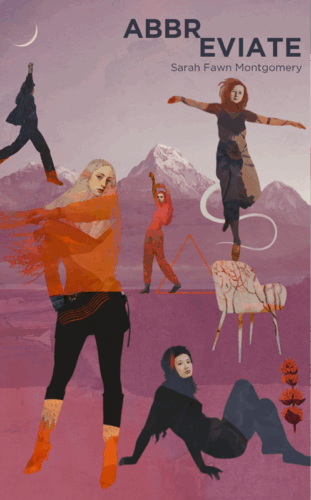

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: When I saw that Sarah Fawn Montgomery has a book out this summer (Abbreviate, with Small Harbor Publishing), I knew an interview with her about the book would be great for our site. Our miCRo series is focused on flash, and her book features short nonfiction. We’ve also published her essays twice before in the magazine, one about middle-school science (read an excerpt here) in Issue 17.2, and another about the gendered expectations around dolls in Issue 20.2 (watch her read from the essay here), both on themes similar to the subject matter of Abbreviate. Here’s our conversation over email:

Abbreviate is composed of short nonfiction, what many might call “flash.” What drew you to that genre for these narratives and meditations?

Abbreviate is a small collection of small essays that examines how the injustice and violence of girlhood leads women to accept—and even claim—small spaces and stories. Because this book explores the ways girls and women are haunted by abbreviation, erasure, and socially imposed insignificance, flash is a way to embody these ideas through form. This collection not only examines seemingly small stories like the girlhood play of Polly Pocket and at planetariums, but it also explores the ways trauma like domestic violence and sexual assault are minimized, girls and women made to feel small as a result. The world often teaches young girls compliance through silence, a kind of self-erasure, so small essays seemed an essential way to replicate this feeling of smallness.

I also became enamored with flash because it blurs genre, and as someone who writes nonfiction and poetry, I love the way the lyric flash form honors both, while also creating something new. Genre, like gender, is a construct, so I was particularly interested in exploring these constructs throughout the collection, asking readers to reconsider where the supposed rules and requirements for each originate, why and how they are enforced, and why it is important to resist and remake them to reclaim space on the page and in the world.

Some essays in the book use second-person point of view, others a plural first-person perspective or the singular “I.” What about those modes appealed to you for different essays?

I was interested in playing with point of view to examine how we process trauma and store memories. Point of view is, of course, a narrative strategy for building tension, vulnerability, and intimacy, but I was especially intrigued by how perspective influences the ways we write about violence and injustice and the ways audiences interact with these kinds of stories.

For example, some of the essays in this collection are written in first person to render intimate experiences that have haunted me throughout my life. These essays examine the history of domestic violence in my family, the fear I felt as a young girl trying to hide from predatory men, the story of an abusive college relationship, or the casual misogyny I experienced from a friend’s husband. First person allowed me to focus on intimate specifics, inviting readers to know my secrets and experience my shame. It was essential in these pieces to use “I” in order to call attention to the fact that these were real lived experiences, a truth that heightened the personal and political stakes.

In other essays, however, I employed the plural first person to write about a collective group of girls and women. I wasn’t speaking for all girls and women, of course, but rather the groups I grew up with, the ones whose histories intertwined so intricately with mine. Not only did we share the experience of growing up in our small town in the ’90s, but we also shared how this shaped our body image and experiences with disordered eating, our attitudes about sex and desire, as well as the traumas of predatory teachers and sexual assault. In many ways we protected one another from the adult world, operating as a family, as lovers, as a unified consciousness that regulated ourselves according to strict gender rules but who also supported and encouraged our unique identities. The plural “we” was a way to represent this unity, this fierce loyalty, the loving protection of girlhood friends, as well as to voice the shared experience of being ignored, being erased, being seen as powerless by society. The “we” allows us to become more than the sum of our parts, to become a constellation with story and meaning, rather than the lonely, isolated girls we felt like growing up.

And finally, some essays are written using the second person. These essays examine shared stories the reader may have experienced—things like being told to smile, apologize, or hug a stranger or unsafe person as a young child; experiencing the black-light teenage magic of a middle-school sleepover; or getting walked into or bumped by boys and men as an adult, the female body considered secondary to the male desire for space. The use of second person allows readers to place themselves in the pages and reflect on their own experiences with these kinds of events. Sometimes essays use second person to tackle particularly painful experiences that require the distance this point of view provides. In both uses, the second person provides a sense of distance and detachment that reflects the isolation and disconnection many of the girls and women throughout this collection feel from their bodies, their desires, their ambition, and the expectations of the world.

What was the best or easiest part of writing Abbreviate? And, if applicable, what was the hardest or most challenging part of writing it?

The easiest part about writing Abbreviate was that I didn’t initially intend for it to be a book at all! I wrote and published more than half the pieces in this collection before I realized they were orbiting similar themes: a girlhood shaped by neglect and abuse from adults, being saved by the communal care of fierce female friends, and feeling the regret and rage of adult women whose lives have been constellated by harm. I often do this in my work, fixating on an idea and writing about it obsessively until I tire and move on to the next, but I simply never tired of writing about this. Eventually, a collection emerged without me fully intending it, and I think it was this unawareness that allowed me to fully embrace hybridity and the subject matter. Typically, my books are conceived before I begin to write, and they operate by strict genre designations like memoir, essay collection, poetry collection, craft book. But being unaware that I was writing a collection and allowing curiosity to compel the exploration provided me the flexibility and freedom I needed to write this hybrid collection and tackle tough subjects.

The hardest part of writing this collection was revisiting the violence of my past. Many of these essays examine difficult subject matter like childhood abuse, domestic violence, and sexual assault. I’d written about some of these subjects before, but in this book I revisited my earliest experiences with them. It was even more difficult because many of these stories were things I’d been encouraged to keep silent about for many years. They were things like being told little girls should be seen and not heard, should be small and pretty, should aim to be pleasing for the comfort of others. They were things like abusive boys and men in my family, including sexual abuse and an uncle who ran over his ex-wife. They were things like predatory teachers when I was in middle and high school and college. Remembering what you have been required to repress in order to be a “good girl” was a difficult but necessary part of this project, as was confronting the ways society silences girls and women, not for their safety but because the world values compliance and submission.

What creative projects are you working on right now?

I just published Nerve: Unlearning Workshop Ableism to Develop Your Disabled Writing Practice with Sundress Publications. The craft book interrogates power and privilege in the creative writing classroom, making space for disability, chronic illness, and neurodivergence by offering readers essential tools and techniques to develop their own disabled writing practices. To go along with the recent release of this book (which is available for free in digital and audio formats as part of its accessibility mission!), I’ve been writing a lot of companion pieces. These pieces explore everything from ways to unlearn ableist craft advice writers may have come across in traditional writing workshops to techniques for designing disabled writing spaces, or methods to discover disabled forms and structures for creative work. I’m also working on several pieces about ways writing instructors can unlearn the ableist writing workshop and develop more equitable creative writing classes, including essays that will include specific writing exercises and prompts.

I’ve also been writing a lot of poetry centered on my experiences with disability and chronic pain. It’s very difficult to live in chronic pain, and this experience is increased by the inability of others—including friends, family, health-care professionals, politicians, and the abled world at large—to understand. Writing these poems is a way to try and make this knowable for others, but also to understand it myself, because chronic pain isolates us from our bodies and minds, our pasts and futures.

What kinds of things have been feeding your creative side lately (books, TV, film, natural spaces, people, etc.)?

Nature always feeds my creative side the most. I prefer solitude and the ways it sparks wonder, so I spend a lot of time walking my dog in the woods, going as deep as we can into the wilderness until we no longer see another person, until the sounds and stressors of modern living fade, and the two of us allow instinct to drive our exploration.

I also spend a lot of time gardening, which I find to be as creative a process as writing. I love playing with foliage texture and color, plant height, boom color and time and duration, bed shape, and so many other elements to create a sense of abundance in my backyard, as well as to create wildlife sanctuaries. I’m fortunate enough to have several acres surrounded by conservation land, so it’s not uncommon for me to see foxes, bobcats, wolves, deer, a variety of birds including hawks and herons, and all sorts of smaller creatures like rabbits and groundhogs. Nothing brings me more joy than being in the garden, building something beautiful.

Sarah Fawn Montgomery is the author of the flash essay collection Abbreviate. She is also the author of Nerve: Unlearning Workshop Ableism to Develop Your Disabled Writing Practice (Sundress Publications, 2025), Halfway from Home (Split/Lip Press, 2022), Quite Mad: An American Pharma Memoir (Mad Creek Books/The Ohio State University Press, 2018), and three poetry chapbooks. She is an associate professor at Bridgewater State University