From Our Contributors: Zoe Ballering On Sand Spits and Life Spans

4 Minutes Read Time

4 minutes read time

Web and Media Editor Bess Winter: Zoe Ballering’s funny and touching speculative story, “Frango,” in issue 22.1, is one of those pieces you wish would go on long after it ends. Here, Ballering explores the idea of life spans–in writing, and in the world around us.

On Sand Spits and Life Spans

My favorite place on earth is the Bayocean Spit, a thin finger of land on the Oregon Coast that separates the Pacific Ocean from Tillamook Bay. In Oregon we pride ourselves on the emptiness of our beaches, and the spit fulfills this ideal absolutely. When I hike there, I feel almost offended to see another person. Strange, then, that the spit was once a lively and doomed place, rather than a solitary and persistent one. The story of this transformation fascinates me, because it touches on a topic that I often return to as a writer: what happens when the things we love—whether beings, objects, or places—have life spans that do not match our expectations?

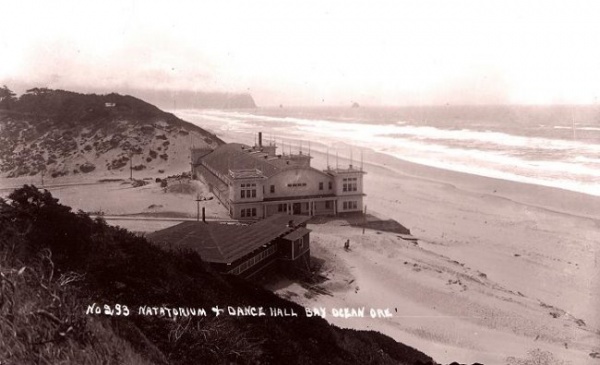

There used to be a town called Bayocean at the tip of the spit and, as far as towns go, it was remarkably short lived. Bayocean was founded in 1906 and during its heyday it boasted a saltwater natatorium, three dance halls, three hotels, and a theater that could seat a thousand people. Some marketing whiz dubbed it the “Atlantic City of the West,” and for a while that name stuck—until the ocean wore down the spit and swept the town away.

Bayocean’s unmaking began with the construction of a jetty in 1917 at the mouth of the bay. The jetty had an unexpected effect on ocean currents and led, over the next several decades, to the severe erosion of the spit. By the time a breakwater was installed to correct the problem, the town had been utterly destroyed. In 1932, the natatorium collapsed. In 1960, the last house fell into the ocean. When I visited as a child in the 90s, I found absolutely no evidence that Bayocean had ever existed. Not a septic tank, not a stubborn clawfoot tub. Not even a doorknob lost in the Scotch broom and salal.

I have always been drawn to stories about life spans. On my bedroom wall hangs a possibly apocryphal quote from Edna St. Vincent Millay: “Parrots, tortoises, and redwoods live a longer life than men do; men a longer life than dogs do; dogs a longer life than love does.” Millay is delivering an extremely bitter take on love, but I also read, in her strikingly matter-of-fact list, a sort of awe at the sheer variety of life spans. I share her awe, and I often find myself adding on to the sequence she started. Even the briefest love tends to outlast the mayfly, which belongs to the order Ephemeroptera, a name derived from the Greek word ephemeros or “lives but a day.” The Greenland shark, which can live up to 500 years, must seem immortal to the mayfly. Sweet Frango is caught somewhere in between—a voice-stealing blob who appears to have a lifespan of a single year.

The crux of “Frango” is not just that Frango’s life span is so much shorter than Maggie’s, but that she doesn’t know it. “Frango” is ultimately a very weird love story, chronicling a relationship that is neither wholly platonic nor wholly romantic. Maggie loves Frango, and so she never stops to wonder how long he will live. She assumes his life span matches hers, because she can’t imagine being in the world without him. But Maggie is wrong—as wrong as the Bayoceaners who built a town on the edge of a wild ocean and believed that it would never wash away.

The turning point in “Frango” happens on a beach that I based off the Bayocean Spit. It’s the moment when Maggie realizes that Frango is aging far quicker than she expected. I chose the setting to create the effect of life spans stacked on top of lifespans: Maggie lying on the spit, Frango lying across Maggie. Both Bayocean and Frango represent a shocking rupture between what we expect and what we get. We want our blobs to live, our towns to grow. It is these types of stories that call to me—stories about brief exaltation, foolish hopes, and irresistible folly; stories that emerge, strange and sad and shining, from the rupture.

Zoe Ballering’s short speculative fiction has appeared in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, Hobart, and Craft. Her debut collection of stories, There Is Only Us (University of North Texas Press, 2022), won the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction. She lives in Portland, Oregon.