From Our Contributors: Louise Ling Edwards on Learning Mandarin

5 Minutes Read Time

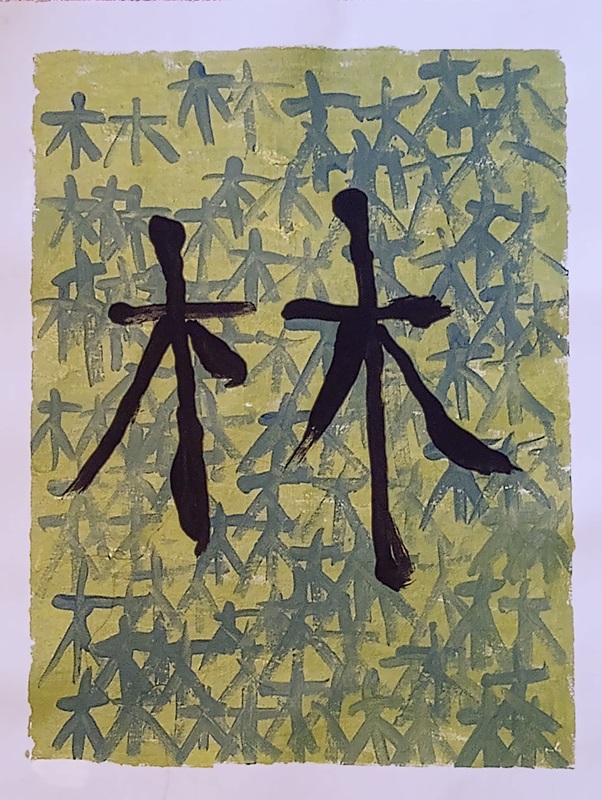

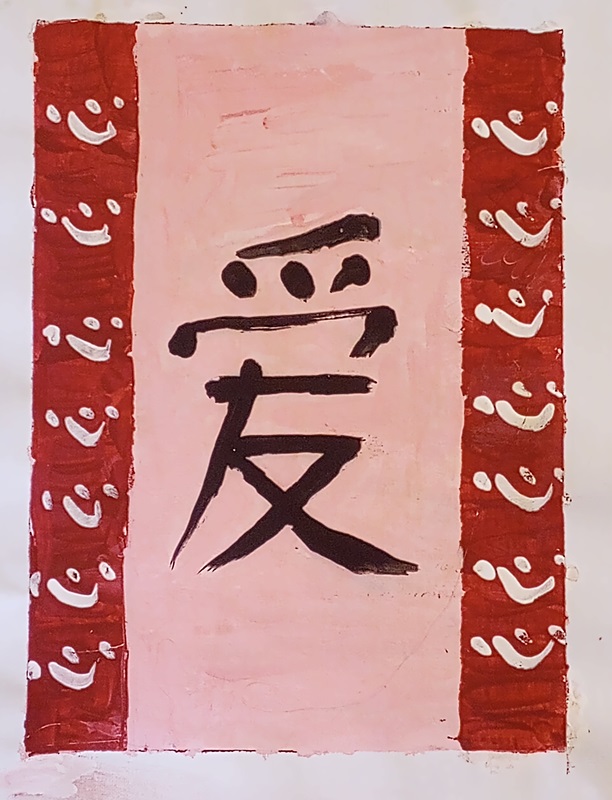

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: In our spring issue (22.1), we feature two poems by Louise Ling Edwards. “Mourning Ritual Cento” is a remarkable cento based on writing from family members, and “Pleco” is about intimacy and distance—as well as the title app, Pleco. Edwards shared with us this essay about her relationship to the Mandarin language, and how it relates to “Pleco.” We’re so glad she also sent three paintings with calligraphy from the Mandarin language, to literally illustrate her points.

On Learning Mandarin

When I was about four years old, my dad taught me how to write my middle name in Chinese: A long stroke down. Make a cross. Add two diagonal lines moving down and away from the intersection—branches. A tree. Repeat for a forest.

While I didn’t grow up speaking Chinese, my grandmother’s native language, I learned how to write my middle name—my grandmother’s surname—in Chinese first. Chinese felt logical to me. In English, I didn’t understand why my middle name started with L. But in Chinese, it made sense that my name meant forest and looked like a forest. Pictures were easy for my young mind to grasp. The movement of my name felt right in my body: small hands gliding magic markers on paper, crafting forest upon forest. Meaning and form converged.

That was an adage that got repeated throughout my creative writing classes in college: The form of a piece should convey or complement its meaning. I found myself often using forms that broke down binaries between prose and poetry: prose poems, lyric essays, pecha kuchas, haibuns. I found myself trying to break down binaries within myself, writing about my experiences as a biracial and bisexual woman. The body of my writing was my body.

While I wrote entirely in English in college, (I just tried writing my first poem in Mandarin only this week), I like to think I got some practice writing in ways that mirrored how Chinese characters operate. However, when I moved to China in 2016 to teach English at an agricultural university for two years, the difficulties of learning Chinese were painfully present. When I arrived in Beijing, I took an intensive beginning Mandarin course that covered one year of college Mandarin in two months. Each day we learned how to read and write fifty characters and had a quiz on them the following morning. I was excited to be learning my grandmother’s language, but it was also exhausting. Each word felt precious and concrete. If I could remember the word for noodles, I could order them in the cafeteria the next day.

One day, one of my classmates advised me to download the phone app Pleco—a digital Chinese dictionary—which changed my life in China. I no longer had to hold every word in my brain or fear forgetting what I wanted to say. I could look up new words when I needed them. I was constantly Pleco-ing my way through interactions: buying a cell phone, picking up mail, getting my residency permit. One day while I was teaching English and Pleco-ing a word mid-activity, one of my students peered over my shoulder and asked, “Why are you always looking at that fish app?” It was the first time I noticed the app’s icon: a blue square overlaid with the calligraphy 魚 — the Chinese character for fish. It felt appropriate. Learning Chinese was like being a fish: water flowing over gills, taking in an environment through the body, memorizing the movement of characters in my muscles, learning a place as fast as possible.

After returning from China, during my MFA program I fell in love with poems by 李立揚 (Lǐ Lìyáng or Li-Young Lee). I enjoyed how Chinese language and literature felt so present in his writing even though he was writing in English. For example, in “Furious Versions” he imagines Du Fu and Li Bai, Tang Dynasty poets, at an intersection in Chicago’s Chinatown. In “A Table in the Wilderness” Li’s lines describe the writing of specific Chinese characters. I adopted his same strategy in my own work. My poem “Pleco” begins: “A field with a lonely base / is a fish. If you want to be / traditional start a fire.” It describes the components of 鱼 (fish), which is formed from 田 (field) and 一 (one) in simplified characters. In traditional characters, the bottom component of fish changes to fire: 魚.

I wrote “Pleco” in a moment of anger at the end of my MFA when I was tired of being asked by peers to explain Chinese language and culture in writing workshops. And while anger and grief are present in the poem, I left the writing process feeling compassion. I remembered moments when others felt frustrated because I didn’t understand what they were saying in Mandarin, and times when I needed help understanding a culture I was just beginning to learn about.

I remembered, when I speak Mandarin, I speak with love. My grandfather met my grandmother when he took her Chinese class. My college girlfriend and I bonded over our shared heritage and shifted between English and Mandarin in our conversations. And though we’ve long since broken up, she’s still family.

Mandarin has created me—it is my center, my heart. And though sometimes I still don’t understand it—language, love—I’ll keep trying to learn its intricacies.

Louise Ling Edwards is a poet and essayist from Saint Paul, Minnesota. She has also lived in Shanxi, China, and currently lives in Columbus, Ohio, where she received her MFA from The Ohio State University. Her writing is found or forthcoming in Conduit, Gulf Coast, Ninth Letter, and Smartish Pace.