Wait It Out

36 Minutes Read Time

“Now you need not die again, but still I wish you were here”

– Katherine Anne Porter, Pale Horse, Pale Rider

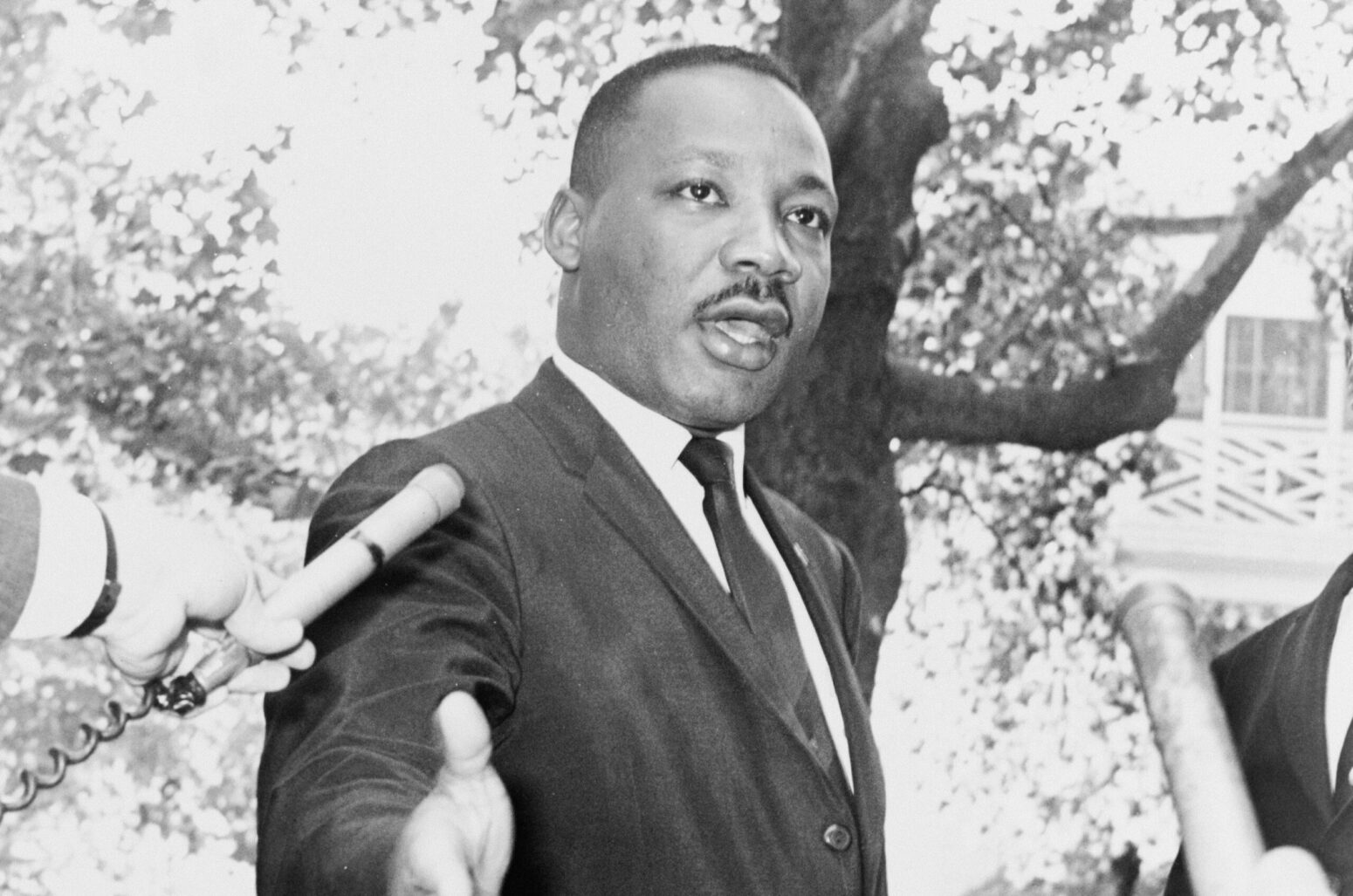

My nephew is writing a book, he says, about Martin Luther King, Jr.

“Now why would you do that?” I asked him. “Pick a topic without so much competition. Who’s going to read your book?”

Ask him, and he’ll tell you he’s a historian. He specializes in the twentieth century, he’ll say. (He has a master’s degree. He teaches at a community college.)

“Write about some minor character,” I suggested. “Who was at the front desk that day? Who was making up the rooms?”

“What?”

“At the motel.”

Blank look, as ever.

“Where King was killed? Randy?” This historian nephew of mine, did I really have to tell him where the man, his subject, took his last breath?

He nodded.

“I met the busboy who was there when Bobby Kennedy was shot. You know that photo? The kid in the kitchen? The white jacket?”

Another nod.

“I met him once. The busboy.”

I’ve been telling Randy crazy stories since he was a kid. When he was in first or second grade, he asked me what my “real” name was, as in not Aunt Judy, not Mrs. Roberts. He seemed a little old to need help piecing this together, so I said, “When I started teaching, they took it from me.”

No reaction.

“My name,” I prompted him.

No laugh, no quizzical look.

“They took it from me in the front office. They put it in a little box and issued me ‘Miss Greene,’ then let me exchange that for ‘Mrs. Roberts’ when I got married.”

Nothing nothing nothing. He just looked at me.

Apropos of his learning about the JFK assassination in school some years later, I told him I’d been there that day, in Dallas. “I was standing on the grassy knoll, in fact,” I said. “But nothing happened there. I’d have known it.”

Where I’d really been was in class. (Who cares where I was. But people tell these stories.) I was still a new teacher, still Miss Greene, when the secretary rapped on my open door and motioned me out of the room, shutting the door behind us. Down the corridor I saw the principal at another door.

I went back into the classroom with my hand still over my mouth. That’s probably part of the story some of my old students tell now, a loss-of-innocence story, seeing adults upset, their teachers and then their parents.

Randy’s angle for his MLK book—excuse me, not his angle, his thesis—is that’s the moment America truly lost its innocence, when King was assassinated.

Well. He should be embarrassed even to say this. I looked at the ceiling when he said it, so he couldn’t see my eyes rolling. “There was never any innocence,” I told him. “That is important to remember.”

“You hear people say it about John F. Kennedy sometimes,” he said.

“Yes.”

“But my thesis is that it was actually later, once there’d been some, well, piling on.”

It seemed a small piece of cleverness on which to base a whole book. But my nephew is not going to write this book. And if he did, there would be something ignoble about it. He’d get some obvious detail wrong, or straight plagiarize. What appeared likeliest to happen now was that he wouldn’t ever bring it up again, and neither would I.

Randy is my sole heir, the only child of my only sibling. “Someday this will all be yours,” I like to tell him, gesturing to the four walls of my room. He laughs dutifully.

So, what is mine to leave? Not the streams that will stop: pension, Social Security. But there is a small life-insurance policy and a couple of retirement accounts, mine and my husband, Adam’s. It would be a lot at once, I think, as a windfall. Not change-your-life money, though, and not very impressive as accumulation, the work of two lifetimes. I may well outlive it.

Sometimes I open the file cabinet by my chair and read the folder labels: life insurance, pension, Social Security—Judy; DNR—Judy; Power Atty. [Fin., Med.]—Judy; Death Cert.—Adam; Archives [All]—Adam (this is a fat one). And so on. All in my hand. Most full of papers that I, being of sound mind and body, have signed, giving over control of myself to my nephew, Randy.

My checkbook, I hate to admit, has become hieroglyphic. What fills it is only arithmetic, I know, but to review its numbers and the words describing them, written in Randy’s block letters, requires concentration I am less and less able to muster.

Randy writes and records the checks, and I sign them. There is one big one per month to this place where I live now, its name so corny and insulting I am loath to repeat it. We’ll call it Sunset Acres. And there are others, some regular, some miscellaneous. I think it would be easy to sneak bits here and there. You wouldn’t have to be smart. You’d just have to be not old.

Randy makes the hour-long drive to see me once every two weeks. Every other visit he brings his wife and children. They are all wholly nondescript. The children might as well have the same name, though one is a boy and one is a girl. Call them both Chris, say, or Marty. Call their mother the same.

They are known here, at Sunset Acres, Randy and his Martys. They may breeze in and out as they please, and what pleases them, ostensibly, is this schedule. The schedule is fine. We are not capable of spontaneity with each other, so this regimentation suits. I don’t know a better way. We must keep in contact; it is the expected thing.

Adam was never with me here. He is pre–Sunset Acres, lucky him.

I have his scar tattooed on my body, his whole long bypass scar, all the way down his chest, but miniaturized and on the inside of my wrist. It looks like a scar there, not a tattoo.

I took a photo into the tattoo place, cropped to remove most of the context. Tattoo artists can’t be too squeamish, I suppose, but there was only skin enough in the photo to show contrast with the scar. Nothing to suggest scale, no chest to suggest the heart contained, no belly or shoulders or head attached to the chest. No way to tell that although the scar was not new, at this point the body was dead.

I didn’t do any of that. I wish I had. I think about it constantly, because I should be marked in some way, scarred. He should show on me. Sometimes I take off my wedding ring and look at the pale indentation it leaves. But the ring is not him. I’d have taken the scar itself if I could have, lifted it from him and wrapped it around my arm like a bracelet, a piece of leather.

For a while I had a red marker in a drawer. It is gone now. I would draw a snaky line down my wrist, redraw it when it washed off. I doubt it was Randy who took the marker. It was someone employed here; at Sunset Acres some decisions are made for you. That’s part of what I’m paying for. The marker might have come from the crafts area in the dayroom. It might be back there now. It’s possible that’s what happened to it.

I am not stupid; I can still make such deductions, but I won’t swipe it back. Persistent writing on my skin would be reported to Randy and the head nurse. They would laugh at me, gently, behind my back. I could explain myself, but that would alarm them further and I would be signing up for heavier monitoring. So I tell myself a story about a tattoo.

I was wrong; Randy did bring up his book project again, not the topic in much detail but a bit about the process. It was an attempt to make conversation. The lulls between us don’t bother me terribly, so I let him fill them if he likes.

“I’m reading a lot, Judy. I decided that was the best place to start.”

“That’s good,” I said, unclear what he was talking about. I would follow along from here and make my little noises in response.

He touched the phone in his pocket and looked at the clock on the wall. We were only half an hour into his contracted ninety minutes. That’s what we’ve agreed upon, tacitly. It is long enough, not so short as to emphasize that what there is between us is duty. I picture him leaving here each time in relief. Done for two whole weeks! I feel it too. But what else could we do?

“So much of research is reading,” he said.

“Sure.”

“And so much of writing a book is all the gearing up to write it! Putting your ideas down is the easy part.”

“I suppose it depends on the book.”

“My book, I mean.”

“Oh. Right.” I closed my eyes. I opened them. I decided to bite my tongue.

“Not easy, I shouldn’t say that, but . . .” He touched his phone again. “Not the only hard part.”

“No. I imagine not.”

I should help him out, suggest a cup of coffee, a walk outside; tell him what I’m reading; ask about the children. Instead I let him dangle. I think I am not cruel so much as weary. Talking like this takes such effort. I don’t know how he interprets my behavior. To him, I am probably just old; not a monster, only an obligation. That is the way of things.

Most of the people at Sunset Acres have children. They assume Randy is my son, though I correct them, over and over. Should I describe him? He is balding. He is in his late forties, maybe fifty now. He wears glasses. Myself, I am quite short, my hair is gray, I have glasses too. I don’t know that we resemble each other, though we might. Mostly we resemble the parent-child affiliations here: he is a middle-aged man, I am an old lady. The picture we make fits expectations.

There was a time Adam and I thought we might have to adopt Randy, at least informally. My sister was in a coma after a car crash, and her useless husband—the drunk who caused the crash—was showing his full uselessness. But she came out of it, and he reformed, minimally. They managed to lurch along to the end of their lives, having raised Randy into adulthood. Now I am his problem. And he is mine.

Adam felt more generous than I did about taking in young Randy, but we were both relieved not to have to. Our whole marriage long, more than five decades, we were aware the prevailing presumption was that we didn’t have children because we “couldn’t”—the defects, I knew, assumed to be mine, and poor Adam a saint for sticking by me. Yes, lucky me. Lucky, lucky, blessed me, and lucky Adam too, because we were madly in love.

Our enduring besottedness felt almost as much a secret as the fact we purposely hadn’t had children. Marriage might start out passionate; that could be tolerated so long as it remained subtly expressed, but the goal was mutual obligation. Devotion should persist, a wry aggravation with each other may develop, but any intimation of romantic and sexual attachment was unseemly much past the wedding.

Our secrets were safe, held within the culturally and legally sanctioned setup of our lives. Many people have private desperations and terrors. We also had private delight.

But my grief is borne alone. That is the trade-off, and we acknowledged that the one to go first would be the luckier. I used to anticipate my own relief in learning it would be me. But what could provide such realization? Some diagnosis? No guarantee.

I’d wanted deliverance from my worst fear, and barring that, I’d wanted information: to know who would go first, and when and how. No one can have that either, and Adam would remind me that whoever was left would just have to get on with things.

Now I am not lonely, in a general way; there is no escaping all this companionship. But I am, I remain, in love with Adam. I still want Adam, Adam only, in every way.

Imagine saying any of that out loud, to anyone. I don’t, of course I don’t. It is acceptable to say I miss my husband, but I don’t even say that. I just think about him all the time; I dream about him. He is my first thought upon waking, when I look at the photo by my bed, afraid sometime I’ll forget what he looked like. But I haven’t so far. There is still that pulse of recognition, and then my brain’s reminder he is dead. It’s been three years, and the shock has not entirely worn away.

In many significant ways I am fine. I give no cause for worry: I keep myself clean, I take sufficient nourishment, I do not weep openly, I know what year it is. I can carry on a conversation—it is performative; I haven’t had an interesting conversation in years, but I can do it.

With Randy I add my flourishes, to keep myself entertained, not only to display my lucidity.

“Will you mention Malcolm X?” I asked now, wondering whether the question would seem out of the blue to him. “Part of the piling on?”

“What?” he said. He looked at the clock again. “Yes.”

“Because he helped add up to the end of innocence.”

Perhaps Randy caught my tone, my sardonic emphasis on the word innocence, but he made no indication.

“Right,” he said. “Anyway, for now I’m reading a lot.”

“That’s good,” I repeated.

He changed the subject then, to tell me about the children, about school (things I’d heard before), about some repair to their house, about their old dog. He remarked upon the weather, upon the news of the day. A nurse’s aide came in with a paper cup of pills—they could have been anything; I thought this every time—and watched while I swallowed them. She asked if we would like some coffee.

“It’s decaf,” I reminded Randy, and he nodded.

“Probably better,” he said.

All this had happened before, the exact sequence: the interruption of the girl with the pills, an offer of coffee, my warning about it. Something would change sometime; there would be real news, a disaster; we would turn on the TV to listen to people talk about it.

We received our coffee and thanked the girl, and then Randy said to me, “Listen, Judy.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’m listening.”

“I’d like to come every three weeks instead of two.”

“That’s fine.”

“With the kids getting older and all their activities, it’s hard to get away so often on a Saturday, even for a few hours.”

“That’s fine.”

He tipped his head at me. I shrugged. “It’s fine, Randy.”

I smiled at him, closemouthed, to show how fine it was, and also to give my relief an acceptable outlet. I could not clap my hands at this news of my extended reprieve. I could give him a demure old-lady smile, though.

“I think you’re set up for now,” he said. “We paid your rent early last month. We’ll pay it again in three weeks. There will be time.”

He stood and set his coffee on my desk. He picked up a pen and leaned to the calendar on the wall. It was a big one, for old people. I could see it from where I was. I could see anything in the room from anywhere else. He wrote RANDY in the square for three weeks from now, filling up the whole space.

“Okay?” he said. “Do you need anything?”

I shook my head, still smiling.

“Shall I look at the checkbook?”

“No.”

“Really?”

I shrugged again. “I don’t care. Be my guest. You know where it is.”

He opened the desk drawer and took out the familiar (inscrutable) little book. It’s had the same cracked green vinyl cover for decades.

“Why is ‘phone bill’ circled in pencil?” he asked.

“I don’t know.”

He read for a minute more, flipped pages, shrugged himself. Maybe that’s how we could communicate. No more agonizing chitchat, just endless shrugging back and forth.

He closed the book and put it back. “I think you’ll be fine for three weeks.”

“I’ll be fine.”

Our coffee got cold, our remaining minutes ticked by, and Randy began his extrication. There is a ritual to it. It starts with him saying “Well.” He said that, then performed the other steps—the standing up, the unconvincing hug, the putting on of his jacket. Then held up his hand in the doorway before showing me the back of him, all while we each said goodbye multiple times.

I could imagine the conversation with his wife when he got home.

“How did she take it?”

“Fine. You know how she is.”

“You’re making an investment, Randy darling. Someday you won’t have to go at all. Someday what’s hers will all be yours.”

Here’s how I might hide stealing, if it were me: pad each line item, decrease the balance at the top of a new page, practice bad penmanship. I am easy to fool, I fear. So easy Randy could do it.

But he wouldn’t. I know this. The very thought is unfair to him, not to mention unflattering to me. It makes me a caricature to indulge in this kind of elderly paranoia.

“Good luck on your little book,” I told him, though I knew he was already too far down the hall to hear me.

Three weeks later Randy showed up with his family. In my room I have my chair, and there is a two-person love seat. The children sit on the floor, elbows on their knees, chins in their hands. They stare at the carpet. The family visits are shorter, a single round hour. I wonder if there is some enticement afterward, ice cream or McDonald’s.

Rent was due. Randy went straight to the desk drawer. “Judy, I’ll run a check to the business office now. Okay? Right on time.”

He wrote it out and handed it to me to sign. I pretended to study it. I could read everything, the numbers and the words; I could understand them. But I have to pay closer attention than I used to, and it reminds me of those dreams when you can’t walk in a straight line or push buttons on a phone. Concentration dreams. Frustration dreams.

I took the pen Randy offered and signed the check.

“Be right back,” he said, and I was left with the children and the wife.

We smiled at each other, the wife and me. The children unglued their faces from their hands. One looked at the clock. They both looked back down, reglued themselves into their default postures.

“Judy, what’s new,” said the wife—I will admit I know her name; it’s Nora. (The children are Marc and Celeste. Marc is eight and Celeste is ten.) “What’s new?” Randy’s wife, Nora, asked me.

“Nothing, of course,” I said.

She laughed.

This type of laughter I’m not supposed to notice, not really. But I recognize it. It’s the sound I would make when a fourth grader said something surprising or precocious. And I’m sure it irritated the children sometimes too.

I let her laugh by herself, and when she was done, I said, “Tell me what’s new with you, then.”

“What’s new, kids,” she said. So we would pass around this question until Randy got back.

When he did, she asked him too—“What’s new, Randy?”—and winked at me. He looked my way. I shrugged.

“Nothing,” he replied.

“You and Judy!”

“Your book,” I said. “That’s new. Right?”

Nora looked at him, where he still stood in the doorway. “It’s just an idea for now,” he said, tipping up his chin to fix his attention at the bare wall above our heads. “Just reading, so far.”

I sensed this visit had taken a curious turn. “But you have your angle, Randy. Your thesis?” I raised my volume. “Tell us again.”

It seemed that Nora should have asked him then, “What book, Randy? You’re writing a book?” The children should have looked up and around at that. But she only smiled and patted the seat next to her. “You can tell me later,” she said, sotto voce.

I think Randy saw me as a safe vessel for his ideas, notions of himself that were, perhaps, bigger than a middle-aged community-college instructor with two kids and a wife and a house needing repairs might let on. I wasn’t his boss, or his students, or his family, or his mortgage holder. My expectations of him were delineated. And I was also “safe” because he assumed I would be forgetful. It was as good as talking to a dog.

He handed me a sheet of paper. “Take a look at the receipt if you like, Judy, and I’ll file it for you.”

I performed the same show as for the check, allocated a minute of concentration to the receipt, then gave it over.

We filled up the hour. The children were made to remind me what grades they were in and which subjects were their favorite. (“None,” Marc said. “Gym,” said Celeste.) I was tempted to give one-word answers too, to Nora’s questions about my meals and activities and neighbors, topics we’d been using for years to generate conversation. Fine, I would like to tell her. Everything is fine!

When they left, having gone through a series of farewell steps similar to Randy’s solo ritual, with a reminder he would be back in three weeks, not two, I could hear little Marc’s voice in the hall, its piercing register carrying his words even as they strode away: “Wait, why does she live here, again?”

Fundamental to the Sunset Acres operating philosophy is the assumption that what everyone needs, constantly, is company. I’m not saying I want none, but I am weary of the tendency to fret over an inclination toward solitude: What’s wrong? We didn’t see you at game night. I suppose—I know—this is the case out in the world as well, but any such phenomenon gets concentrated here.

I make compromises with the staff to stave off their pestering me. I take one meal per day in the common dining room. I show up for at least one activity per week, usually movie night or a musical performance (piano-playing relatives of residents—there is an electric keyboard in the dayroom—or a church or school group); never bingo or crafts. I use the lending library (two tall bookshelves, also in the dayroom) and volunteer once per week for a two-hour shift there. I have my hair washed weekly by the visiting hairdresser and chat amiably with the other ladies in the narrow beauty parlor while we wait to dry. I think I am seen as standoffish but not exceedingly so. I can live with this assessment, but it takes some strategizing to maintain.

When Randy and I were looking around for a place for me, I took the position that the smallest room on offer anywhere was fine. I wanted my own bathroom, a window, and a door I could close. I didn’t care about square footage.

In our initial meeting with the Sunset Acres director, when she was going over the layout choices, I interrupted to tell her the studio floor plan was acceptable. “There’s also a roommate option,” she said. “You would be paired with another lady.”

I absolutely would not, though a single studio was more expensive than half of a larger double room. “I am putting my foot down about that,” I said. I looked from her to Randy and back. “No roommate.”

“Would it really be so bad?” the director asked, seeming not to care about the roommate situation so much as she did about trying to get a bead on me. Just how disagreeable was I likely to turn out to be? I would realize later that this was my first indicator there would never be any casual, face-value conversation with staff here.

“The studio is fine,” Randy said, and I was glad for his backup and an end to this part of the meeting but also resentful it was only at his assent that the director was ready to move on.

Many times I’ve had urges to tell crazy stories here, when a conversation meanders or goes on too long, or someone asks me a nosy question. My husband was an astronaut, for example. (He was an electrician.) Or I met the Queen Mum once, but I was thrown out when I thrust my hand at her to shake. (We visited London and saw the Changing of the Guard. It seemed very silly, and I felt silly standing there for the duration among the other tourists.) Or I spent my teaching career on a combination German literature/home economics curriculum in a one-room schoolhouse. (I taught elementary school, mostly fourth grade. I enjoyed my work, but it helped reinforce that I didn’t want any children living with us.)

I don’t tell the stories, though, even just to other residents, because the staff would somehow get wind and I would come in for scrutiny. I think my only slipup so far was drawing on my wrist with the red marker. I still like to think about that, but I won’t do it again. It remains my aim to attract as little notice as possible for as long as I can.

I wasn’t sure whether we would talk about the book project again on Randy’s next visit, though I was certain we wouldn’t talk about why it had appeared to be news to Nora, or whether he had since filled her in or she’d dropped it. I wouldn’t bring it up, I decided. I would pretend to forget. That was what he wanted anyway. Perhaps I would spin some new crazy story for him, have it in my back pocket in case he seemed to need it. Your uncle was a secret astronaut, Randy. I met the Queen Mum. And we never ever wanted any children living with us.

For three weeks nothing happened. We residents of Sunset Acres carried on as we do, the big nothing of retirement living punctuated by the structure of mealtimes and pill times and the activities described on the dayroom calendar.

Then Randy came back as scheduled, and nothing happened. And then two days before he was supposed to return with his family, he called. “Judy,” he said, “is it all right if we come this Sunday instead? The kids are booked solid Saturday. We’ll be running them around all day.”

“Fine,” I said.

But the children weren’t there on Sunday either. Randy and Nora came in explaining how each had ended up at a friend’s house for a few hours that afternoon.

“They’ll be back with us next time, though, I’m sure,” Nora said. She and Randy sat on the love seat. They unzipped their jackets.

“Fine,” I answered. “Shall I order us some coffee?”

No, no, they said. They made a few more noises of conversation, sighed, shifted in their seats. They smiled and tried not to glance at the clock. Then Nora put her hand on Randy’s.

“We wondered, Judy,” he said, “if you would consider moving closer to us. There’s a similar place just a few blocks from the kids’ school. I’ve called for some transfer information, and we brought you a brochure.”

All I said at first was “What?” I’d heard Randy, I’d understood him, but I needed a stall to quite register his statement.

He repeated himself. It had been a lot for him to say at once, and then say again. In acknowledgment of that I waited a few seconds before saying no.

They were ready. This was an initial volley, prepared and rehearsed. I could be pressured over a short time. No doubt they also wanted to impress upon me the inconvenience of these visits.

“We’ll leave the brochure,” Nora said. “You can read it later.” “Please think it over,” Randy said. “We’ll talk about it again.” “I have my friends here,” I said.

“Certainly,” Nora answered. To her credit, she didn’t also say, “You’ll make new friends.”

It might be I’d never used the word friends with them before. I’d mentioned individuals; they knew a good handful by their first names, people in my orbit who appeared and reappeared in the usual ways. But friends in this instance seemed quite inarguable, and it was also an acceptable way for me to gloss what I really meant: that I had all my compromises and showings-up situated at Sunset Acres, my stavings-off, my calibrations. I didn’t want to have to redo all of that, and it would only require greater and greater efforts of concentration. I was too old for a new round of orienting and strategizing. I would not leave.

I was also not going to say that I did indeed want to keep these visits inconvenient, and that Randy and Nora ought to as well. If I were just down the way from the kids’ school, they would end up feeling even more obligation: we would be back to every other week—at least!—plus every holiday, every event. We would be that much further trapped until I was dead.

“It’s fine to come less often,” I said. “You’re busy. I understand. And it is a bit of a drive.” Then I upped the ante on I have my friends here: “I’ve already had so much upheaval.”

I saw that one land. They were committed to their position, but Randy exhaled audibly; Nora pursed her lips. She looked at him, then she looked back at me. They made no answer. It seemed I’d tabled the topic. I wasn’t worried; I would keep saying no.

They couldn’t leave yet, though, not early and not on that note.

Randy cleared his throat. “Do you remember how we set up online payment for your rent?”

“Yes,” I said. I didn’t, of course.

“I guess . . . that if I have to miss a bill deadline, I mean in person, I could pay online and show you the receipt the next time I see you.”

“Fine,” I said.

“For the short term,” Nora said.

“It seems you like to be involved and see it happen—and I understand that—but if I can’t get here, we don’t want to be late.”

“No.” Could I not just keep track of and pay my own bills? This was something like the thousandth time I’d asked myself that. But no. I could not, actually. Soon my money would be taken care of wholly without my participation, like the pills I was not permitted to store in my room—and which, frankly, I would also have some trepidation about keeping sorted on my own.

I looked at Randy. His brows were drawn together. He wasn’t looking at me, nor at Nora. “Yeah,” he said. “I think that’s what we’d have to do, online pay.”

Stealing had likely occurred to Randy too—as in, wanting to avoid any appearance of it. To have to manage someone else’s money like this was, by definition, awkward. I acknowledged that.

But it was lucky for me, wasn’t it, to have next of kin. Better than some assigned professional minder: a caseworker, a lawyer, a “geriatric-care manager”—that was one phrase I’d heard. The nosiness of such a stranger could inflame my elderly paranoia.

I had been taking some pains to remind myself of what I believed and what I did not. I didn’t really think my nephew was stealing from me or that, say, drawing on my wrist with a marker accomplished anything at all; I hadn’t talked myself into any of the content of my crazy stories, whether told or only imagined. It was as important to keep these categories clear in my own brain as it was not to arouse attention with my behavior.

We were quiet for a bit—it might have been only thirty seconds or so—and then Nora squeezed Randy’s hand. He turned to her and she shrugged. They looked at each other for a long moment, forgetting, apparently, that I could see all of this, here in my tiny room. I could also see a smirk appear at one side of her mouth, but when she turned to face me, she pushed it into a full smile.

“Judy, Randy told me some more about the book he’s working on. I pried it out of him!”

She was making an effort, changing the subject, lightening the mood. Fine. I would play along. “Is that right,” I said.

“I even offered to be a research assistant or a proofreader.” She stretched her smile to its limit. “Or maybe you would want to do that, proofread. I bet you’re good at it.”

I was good at it. I had been. “Sure,” I said.

“I’m so proud of him. I’m going to try to get the kids on board to give him some quiet time to work on it.”

I nodded.

“What do you remember about Martin Luther King, Jr., Judy?”

She said my name entirely too often, as though she were reminding me of it. Conventional wisdom held that people loved to hear their own names, but I could detect the exertion in it, the reminders to herself about how to deal with me, how to remain patient, how to get through these visits.

“All the usual things, I suppose,” I said. “The things people remember.”

Nora had taken a deep breath before coming in here, and she was looking forward to letting it out when they left. Randy’s efforts, in contrast, seemed less calculated, less, well, effortful. He had hit upon a sort of good-humored neutrality toward me long ago and had never seen a need for a strategy update.

“Do you remember where you were when you heard he’d been killed?” Nora asked.

So much for lightening the mood. I considered making up a crazy story, but I didn’t have the energy to quickly work out some details.

“I was at home,” was all I said, and it was the truth.

“How did you hear? Was it on the radio?”

“We did have television then. I’m sure you’ve heard of Walter Cronkite.”

My, I was amusing, wasn’t I? Such a feisty old lady! But what a topic this was for anyone’s amusement. Nora kept up her grin. Randy looked at me too, with a smile half-suppressed.

Then she asked, “What about JFK?”

“Oh, who cares!” I heard myself say. “Who cares where I was? My goodness, people love their little stories.”

Before they could respond I tried to recover. This outburst was already more trouble than it was worth. “Listen,” I said. I held up a hand. I dropped it. “I’m not going to move. It’s fine to come less often.”

“I’ll leave the brochure,” Randy said. He pulled it out of his pants pocket and set it on the table by my chair. “We don’t have to talk about this more right now.” I glanced down. Stock old people smiled back at me.

“And you’re right,” he went on. “People do. They do indeed love their own stories.” Such studied patience in his voice, patience to cover rebuke. Or to underscore it.

“Judy,” Nora said, “is it that you would be even farther away from Uncle Adam?”

I’d heard her, but her volume was low, so I said, “Excuse me?” Adam’s grave was in a cemetery less than a mile away, but did I really have to say to them that here on the other side of death I was already as far as I could be? “It’s fine to come less often,” I said again.

“I’d like to believe Uncle Adam would think we’re taking good care of you,” Nora went on. Her grin was gone. I had missed its fading. “Randy especially.”

Who’s Adam to you, Nora? I wanted to say. ‘Uncle’ Adam? I met her eyes. She held mine. I blinked and then looked to Randy to seek his gaze too, but he was looking at the floor. So I raised my voice to gather them both: “Adam doesn’t think anything anymore.”

“Judy, I’m sorry,” Randy said, by way of greeting, when he came in next time. “I’m afraid I have only an hour today.”

“That’s all right.”

“Marc has Little League, and Nora needs to take Celeste to the dentist.”

“Fine with me.”

“I am sorry.”

I didn’t have anything else to say on the topic. We did our rent-paying routine, our chitchat; I watched him look at the clock.

“I’m sorry,” he said, yet again, “but I will have to get going. Is there anything you need?”

“No, Randy.” Yes, of course, Randy. What a crazy story all of it would be to tell: what I needed.

It would be handy to love Randy, wouldn’t it? A part of me wished I had the expected family feelings. I might be somewhat assuageable that way. Though if I were wishing at all, I might as well wish for Adam back.

I would say nothing out loud, though—and then I did: “I miss Adam.”

Randy looked at the clock and back at me. He was closing in on fifty-six minutes. He had only an hour today. His jacket was back on but not yet zipped.

“I know,” he said.

He didn’t, but that’s what you say.

“Is there some kind of . . . anniversary?” he asked. “Coming up?”

“No.” It was just the truth, every day, but such an inadequate statement that there was no reason to say it. I shouldn’t have. I wouldn’t do it again. It only trapped us, both unsure what to say next. And Marc was expected at Little League. Celeste had the dentist. I had movie night, after supper in the dining room with everyone. Randy had his book, or the idea of his book, and he had Nora to drop the subject or let him tell her all about it.

For years I had wanted to say aloud I miss Adam, but the one I wanted to say it to was Adam, because whenever there had been anything to tell, I’d wanted to tell him. Ah, Adam, here I am, the less lucky, the remainer, the one who fears forgetting your face.

Oh, but that is dangerous, to descend too deep into longing. Better to skim it. So my heart is broken? All right, it is broken.

But what would you do if you were me, Adam? How would you hold longing? Would you be more peaceably resigned? More sanguine about Sunset Acres, more patient with my nephew? Would stealing cross your mind? And if it did, would you care?

Would you listen to our sole heir talk about his book, this fiction of innocence? Would you tell him where you were? When MLK was killed, Adam? JFK? RFK? Malcolm X, even? When the various wars began and ended? When the wall came down? On 9/11? Upon authoritarianism come to twenty-first-century America? And where you were when I died, Adam, if I had been the luckier?

Among the things I shouldn’t say out loud, to Randy or anyone, is that I wish I were dead. It would sound dramatic, but it’s not, not really. I will take no rash action—I don’t have it in me—but how could I not wish for the end of longing?

Randy was here, in my room, still. He had to go. He was waiting for me to wrap this up and release him. “Please go,” I said. “I will see you in three weeks. Go ahead now, Randy.”

When Adam died, I was there. I knew it was happening. Another heart attack, like the first and unlike it. The realization was bodily, a feeling like implosion. I was helped to a chair by an EMT. Randy was called. I remember saying to someone, “My nephew?” A question in response to a question.

The EMTs hurried and then they did not. One crouched in front of me, a young woman. We made eye contact and held it. She wanted me to drink a glass of water. I did it. I understood.

This was how it had happened, then, and I was the one left; a pulse of relief for that knowledge. But I miss Adam. So my own heart had broken. All right, it was broken. Now I would have to wait it out—it, this whole long rest of my life—with a broken heart.

I wished I could tell Adam I would get on with things, that I still acknowledged my being left had always been the gamble. But the living are of no interest, no concern, no possible utility to the dead. So I tell myself; I tell myself, the only person to whom it could yet matter. I tell myself: Wait it out.

Read more from Issue 21.1.