Track 3: Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair

21 Minutes Read Time

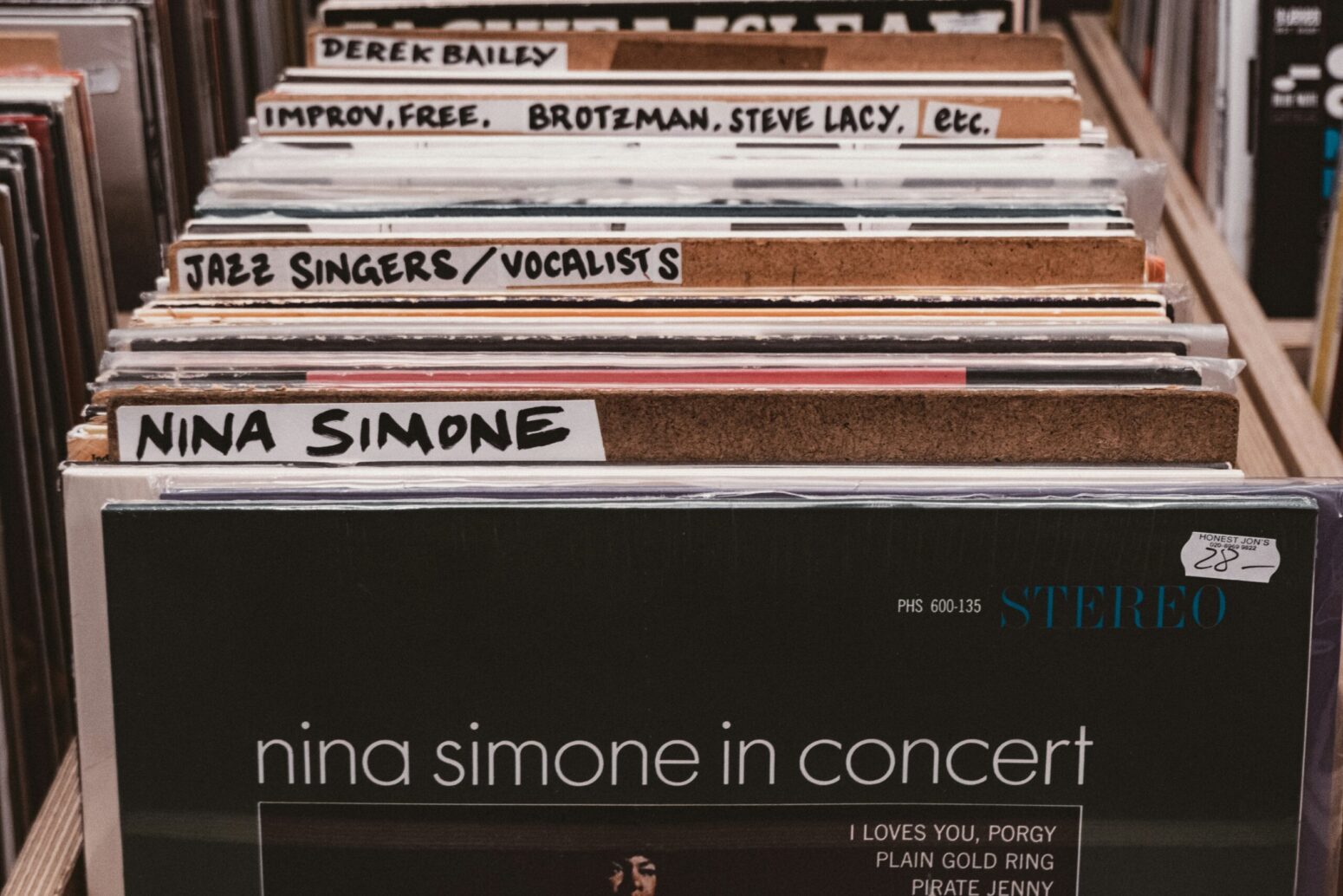

Compact Jazz recording, 1989

Nina Simone, accompanying herself on piano

Every instant is at once a giver and a plunderer.

—Gaston Bachelard

In 1980, my mother lay dying. Her death that July guided me north to a high Victorian mansion in upstate New York and, within just three days, to my beloved. He too was mourning—his marriage a heap of burned and trampled things. When a coup de foudre, “cup of lightning,” strikes two people simultaneously, surely a readiness to love came first. This might have been experienced as grief, a concavity so intense it sinks to all areas of the human heart, or quite simply an age-appropriate hormonal overflow. In any case, mind and body are in concert: Something must be done.

The mansion housed composers, writers, visual and fabric artists, sculptors, and more. There was a grand staircase, chapel, Tiffany mosaic and glass, lordly dining hall, and a cozy cocktail room with a mahogany sideboard serving as a kind of bar. Guests arrived, bottles in hand, most with the intention of sharing. Nina Simone’s sultry, sorrowful ballad poured from a small boom box balanced on a chair. She was singing our song, but we did not know it was our song.

When my beloved walked in, I observed the following, through willfully rosy lenses:

His height, at least six-foot-three

His head of black black black hair

The purest eyes, wild-chicory blue

Clean-shaven jaw and chin

Cuffed shirt, top button open to a V, sleeves rolled up,

those forearms

Khakis cinched with a fabric belt

Topsiders, no socks

The way he walked, soles down first, not the heels

The strongest hands, male-model perfect

Nails with milky white lunulae

Marlboro Lights and a bottle of Seagram’s 7 he didn’t share

Accent: New York, Long Island?

Great jokes, delivered flawlessly

So great, we all moved closer

No question, he would be adored

By someone

This is what he was thinking: From the start, I felt at ease—safe, at home. I’m not sure exactly why. My animal attraction was strong. I loved her gestalt—a kind of smart-hippie-nerd vibe. I remember peasant skirts and Indian blouses and sandals. When she dressed in shorts, she resembled an awkward kid, which turned me on. I loved her hair: blonde, curly, and longer then. Her eyes were small and beady—I liked them. She’d read and loved the same poets and novelists I had. After years in business and my tortured relationship, it was a great relief and joy to chat about writing, especially with someone I was attracted to. Writing talk in that context is sexy and exhilarating. She was nondoctrinaire, surprising. She got my humor. A little later on, she belied the standard feminist thing by cooking me breakfast.

The cocktail room also served as an intimate exhibition space. Poets and novelists read, artists cast slides against a makeshift screen. That evening, the room settled into darkness, and Nina was momentarily silenced. A journalist sitting to the right suddenly put his hand on my knee. “Is it my drink, or are these paintings extraordinary?” he said. My beloved sat on my left, and he too slipped a hand into my lap—two offerings, one on each side. I have to tell you the journalist was not my sort of man, though a very fine man in his way. The phrase “in his way” had become a kind of practice for me, a nod of affection toward men who didn’t suit my particular taste. As for my beloved, it was obvious at once we were made for each other. I felt sorry, then liberated.

Nina knew how to summon, as she said, “a state of grace,” a feeling like “electricity hanging in the air . . . like mass hypnosis.” Her breakthrough performance occurred in 1959 at the Town Hall theater on West Forty-Third Street, New York, a venue “for the people” that had launched or featured Isaac Stern, Marian Anderson, Rachmaninoff, and the bebop of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. That night, the audience was filled with intellectuals, men in dinner jackets, bejeweled women, and various artists from the Village, all on their best behavior. The singer wore a white satin gown that draped over one shoulder and hugged her lower back. She was twenty-six. She opened with “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair.”

Something in her magnetic, simmering voice makes it impossible to chat or read or anything else while listening. My arms go limp. Her arpeggios leap and politely recede. She fills the silences, but only just, as if we were napping and she wouldn’t dare wake us. I’m returned to my mother running her fingers lightly over my arm. The rustle of sheets and purr of the humidifier and furnace stirring the air. I could sharpen that description, but I’d have to work at it. I’d have to turn the music off.

In the center of the mansion was a mock-Tudor, four-story stone tower. Once, my beloved and I snuck up the narrow stairs, treading carefully, for the footing was precarious and we were trespassing. Not our given tower, not our daybed and wicker desk. Yes, we were writers, but not as famous as the playwright who alone deserved this magnificent space. Instead, we slept in smaller rooms: laundry room below mine, Ping-Pong table in play at all hours. His little cabin in the woods was like a screened-in porch, not very private, with a wood-burning stove, cot, chair and desk, little else.

At the enormous plate-glass windows etched with filigree and a poem or quote or dedication I can’t recall, we watched light drain from the Norway pines and thought nothing of turning off the lamp, though it was not our lamp. We didn’t care. Below lay a great lawn and, beyond, the fountain and the pool shaped like an infinity sign. There stood Aurora in white marble imported from Milan. Goddess of the dawn, garments flowing, arms raised in ballet’s third, and by her feet an adoring lover. The other pedestals were empty, reserved I imagined for other goddesses and fools.

Our experiment in lust began. So incredibly fast—that mussing of hair, mashed lips, and scraping of teeth. My tongue with its aftertaste of spearmint gum. His breath sticky with tobacco or, wait . . . , black licorice. Was that someone on the tower stairs?

In Fiji it’s a sin to touch a person’s hair, but make him a lover and the taboo disappears.

The French documentary Nina Simone: La légende opens in quivering vintage tones of black and white. We’re inside a car rolling past graffiti-smeared row houses on a city street, and one of her songs is playing, a recording on cassette tape. Unmistakable, that damp sotto voce wail. The camera focuses on the singer in the back seat holding hands with Edney Whiteside, who was her first boyfriend forty years previous. He tries to comfort her, kneading her palm, but she is inconsolable. So many dashed expectations—lovers and two marriages, one lasting just a year, another a full decade; a daughter named Lisa, who would be separated from her mother for long periods of time. Nina regrets this and complains bitterly there’s a grandchild she’s never even seen. Once or twice, she chimes in with a lyric or two, but her heart is not up to it. “That, that’s my music,” she says, dabbing her eyes with a tissue, forehead creased. “I don’t know what, what life is supposed to be anymore. I have sacrificed my whole life to do songs for this race of mine.” Edney kneads harder and says, “Well, that’s what you wanted, Eunice, and you were successful.”

My lover and I left the mansion together in a 1979 Rabbit, drove to Norwalk, Connecticut, climbed two flights of stairs to an attic apartment he’d been living in for a year. On the first floor a gynecologist’s office and, down the street, a chiropractor. Both turned out to be great conveniences (pregnancy, slipped disc). And the apartment! So snug, with 125 years of character! Recognizing something there, I surprised us both by weeping. Silly woman. The broken-tiled bathroom, kitchen with a pile of dirty dishes, bedroom in the middle but no place for a dresser, living room with a nook just large enough for my harpsichord. Could it be? It fit. We fit.

Here’s what he thought: She seemed to like it even more than I’d hoped. I didn’t realize that the “me” details—like the printer’s box with my boyhood knickknacks—would charm her. I see now that she was responding to a “me” that at that point I didn’t think was worth much. The stupid polyester chair where we snorted coke, her first taste of bay scallops, then bay scallops covered in butter and herbs three times a week. The art-house cinema (that incredible short, Harpies). Just happy to think about the future for the first time in years. I had a weird confidence beginning in upstate New York that this was it, an absolutely right match. It was totally unexamined, instinctive, impulsive, and solid. Why I felt that, I really don’t know.

I didn’t know I craved jazz or scallops or dental molding or porthole windows or even the polyester chair—garish red and purple—that unfolded into a ridiculously small bed. Love placed those details inside me with amazing efficiency.

And there was more: I never exercised till I saw him swim. I didn’t know that I didn’t know how to relax until I watched him drag his lawn chair onto the beach, swivel his Coke into the sand, lean back and gaze at the ocean for hours. He introduced me to the sonnet, acrostic, villanelle, sestina, and other forms. Ironically, it was an opened latch, a discipline that steered me away from years of modestly successful free verse.

He too discovered things, grew a taste for Mozart (though not quite exceeding his love of Bach). When they were still a bargain, he developed a systematic approach to outdoor antique shows: Begin in the middle, and weave your way out to the more trafficked tables. His collections of Bakelite, samovars, toy ray guns, and fountain pens crowded the kitchen and filled our meager storage areas. She civilized me, taught me the superior pleasures of staying home, of being true to my word, my family, myself. She pushed me to think of others (like my mom) when I’d rather not; demonstrated the value of steadiness, of doing the drill even when we don’t feel like it, because it’s the right thing to do. She showed me the morality of faithfulness to everyday duties, stopped my roaming eye, lassoed my roaming heart. She helped organize my life, changed all that I was into everything I am.

Don’t ask me to stop the dark spilling from this song. I chose it for that. We listened to other music in that apartment: Sinatra’s “Mood Indigo,” Mozart’s Requiem, Holiday. But nothing came close to the plangent dignity in Nina’s throat. She was the High Priestess of Soul; she owned the song, stripped it down to its melancholic basics. She knew how to

unwrap a chord, slowly, a woman distracted, mired in her thoughts. Her black travels a long distance before it becomes the color of her true love’s hair. Her purest rings out in the dark, suspended before settling on eyes. In Nina’s song, it’s the modifiers that roam: pure, true, black. I care little that John Jacob Niles discovered it and rewrote the melody, that a Mrs. Lizzie Roberts first recorded it in 1916. Their versions seem frilly by comparison.

Here’s what Nina leaves out:

The winter’s passed and the leaves are green,

The time is passed that we have seen. . . .

I go to the Clyde for to mourn and weep,

But satisfied I never could sleep.

I’ll write to you a few short lines,

I’ll suffer death ten thousand times.

So fare you well, my own true love.

The time has passed, but I wish you well.

The Clyde is a river running through Glasgow, proof that the song originated in Scotland, not Appalachia. I think it telling Nina deemed these lines unnecessary. She stops short of the well-worn Romantic tradition, the lover placed on a pedestal like a vase of flowers, the lonesome one reaching, reaching, unable to touch. With gaps and pauses, she focuses instead on the mystery, exploring that Zwischenraum, or space between things, where longing and defeat intermingle. Love’s door, she seems to say, is hinged with pain, a lament that spreads across so many of her other works: “The Other Woman,” “Ne me quitte pas,” “I Loves You, Porgy,” “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” even the sexy songs, like “I Want a Little Sugar in My Bowl.” These in particular we couldn’t leave alone. We’d listen to the point of irritation, then two weeks later listen again.

Here’s a photograph: I’m in the tower, leaning against a wall, the window casting lacteal light. Through his lens, I’m ever so slightly blurred, cross-ankled like the goddess of dawn in her shallow pool. My face so soft and wondrous fair. That blurred. Nothing on but two Band-Aids stuck to my heels. Underneath, skin rubbed raw from a strappy pair of sandals. I remember those blisters—worth the pretty sandals, worth the pain if this man turns out to be the one.

He was the one, the two of us delighted at how we said the very things the other was thinking, sometimes in unison. In Venice, consuming half our honeymoon budget on a gondola ride and curried sole at Harry’s Bar. Riding like oversize teddy bears on a Vespa, simultaneously blind to the dangers of grass shavings and stray gravel. We were both firstlings, loaded down with parental expectations but happy to defy them. We favored indie movies, indie bookstores, mom-and-pop diners before they were trendy. We read Nabokov, Renata Adler, Maxine Hong Kingston, Marilynne Robinson, Chandler, James Baldwin, Ian McEwan, Fitzgerald, and Hardwick. Unhappy in our jobs—he in business, me in adjunct teaching—we decided to jump ship and flee to a small town in Delaware with two toddlers and no prospects. In retrospect, they were all the right moves. We were jealous of each other, but only in one area—solitude, time for writing. Even now, I have to keep my laptop screen tilted so that he can’t see I’m finishing up an essay. As if I were reading pornography. Do they make plain brown wrappers for laptops?

Some people look at a long marriage and think: Those two are amazing. They match, like Queen Anne chairs. Surely they have their problems—disagreements, false hopes (of course he’ll change)—but somehow they’ve figured it out. Life inside their dwelling is calm and respectful. One says, “Please tickle the fire,” and the other laughs. It’s such blatant code. She tolerates his restlessness, and he her lack of adventure. They memorize the steps, avoid the slick spots, pause, consider, and trust.

And yet, how quickly we uncover and probe each other’s faults, rarely examining our own. Not long before we discover what drew us together, what we thought was a lit forest, was partly deciduous. We grow into street angels, house devils, charming our students and nagging our children. We aspire to human decency. Then, while arguing, throw a pitcher or pot of rice, denting the drywall.

Long ago, Mary Kate Waymon stood in their North Carolina living room and “almost died on the spot” as she watched her two-and-a-half-year-old, then Eunice, climb up on the piano bench, put her little hands on the keyboard, and punch out a favorite hymn, “God Be With You Till We Meet Again.” Music was in her genes; the entire family was gifted in piano, harmonica, guitar, and singing. Still, this toddler was something else entirely. She taught herself to play by ear; it wasn’t long before she opened the service in her mother’s Methodist church. At the age of six she was studying Bach with Muriel Mazzanovich (Miz Mazzy)—a highly authoritative yet courteous Englishwoman in town—the year of classical lessons paid for by Mary Kate’s employer. Later, the small community of Tryon raised funds to send her to Juilliard with the aim of readying her to become a concert pianist. Nina suffered her first real disappointment when her application to Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music was rejected, despite a positive response to her performance. It was a decision she swore was based on her race. Instead, she took on students and, to supplement her income, answered a call for an audition at an Atlantic City bar. She was signed immediately, the owner insisting she add vocals to her brilliant piano. She killed it. Her reputation spread like fire up and down the East Coast.

During the sixties, Nina’s compositions were outspoken in their opposition to racism. She joined the civil rights and Black Power movements, marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr., and performed during fundraising events and demonstrations. “Mississippi Goddam,” “Four Women,” “Backlash Blues,” and “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black” were written during this period and inspired other musicians, including Aretha Franklin and Patti LaBelle, and later John Legend, Mary J. Blige, Alicia Keys, and others. The singer saw herself as a griot—that deeply respected West African minstrel who sees and hears and knows everything in a village.

Nina was a champion for “my people” but looked down on her black audiences. She beat up white audiences too, disdaining them while covering their popular songs. She grew demanding and difficult, the result of discrimination, financial turmoil, overcontrolling managers, and: a diagnosis of bipolar disease. A bodyguard was once hired to protect fans from the singer. “I will never be your clown,” she chastised a nightclub audience in Cannes for resisting a sing-along, then trudged through her set, closing with, “I don’t wear a painted smile on my face, like Louis Armstrong. . . . I am not here just to entertain you. How can I be alive when you are so dead?” This behavior came to dominate the idea of Nina—irregular, unwelcoming. Critical work about her now has titles like What Happened, Miss Simone? and Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone.

Years passed. I learned a lot—how, in his mind, the language of physics and theology and the intricate world of a sestina coexist with random bursts of basso profundo: Climb every mountain, ford every stream. Or how the hypnotic rhythms of Arvo Pärt can be spliced in with Bucky bucky beaver, bucky bucky beaver—a 1950s toothpaste jingle. I realized he was a person of lifelong hyperattenuation. A supermarket paralyzes because there is too much going on visually and spatially. Facing an aisle stacked with cereal, he ends up not seeing anything, forgetting what he came for. I tolerated his habit of throwing tissues on the floor till they formed a bacterial mulch around his favorite chair. “Okay, honey,” he often said, out of the blue, a signal like the game of Marco Polo or perhaps the marker of the end of one activity (sitting) and the beginning of another (standing). It wasn’t long before I picked up the practice—an endearment that implied, I’m fine, I see you, won’t ever leave you—whether he was present or not.

Unlike Nina, we suffered no serious mental illness, though the course of a year might include patches of resentment, depression, anxiety, and irritation. She can’t sit still. She gets up from the couch every five minutes to tend to something. She believes this makes her thin, keeps her joints lubricated—a person of industry. But it is difficult for me to function when there’s a lot of movement around me; my brain is so perpetually awhirl that it makes me feel confused, fractured. I’m trying to get her to relax, to break some of her own rules, for life-affirming purposes. But I also admire her stringencies, because they have in a large sense allowed her to be/become so accomplished, as well as to handle the day-to-day necessities. So I am in a way envious, simultaneously taking it as my mission to show her how to give in to pleasure, over and above obligation. This seems more of the essential yin-yang of our relationship, differences that both compliment and mystify the other. We maintain an essentially harmless low-grade state of continuous warfare. Not a bad description of human relations in general.

Today, we’re both hard of hearing, so there’s little whispering or secret-sharing in public. No kitchen murmuring, no restaurant under-the-breath, no “pillow” nothings. He’s easily surprised and, if I approach him from the back, lets out a bark like a pissed-off parrot. He listens to music at full blast, which discombobulates me, as does the music itself. Have I become too sensitive, as he has grown impenetrable?

There are couples that are slow to trust, waiting years before moving in with each other, years before marrying, then a decade before settling on a child or two. We didn’t require a trial period. We were of the same mind, held together by a habit of risk-taking and the willingness to go all in. On the honeymoon in Venice, we threw away the birth control and returned to the States two weeks pregnant. On a long drive back from New Hampshire, we stopped for an overnight in Pennsylvania— hound dog curled on the floor, daughters asleep in one queen-size bed, and, inches away, their parents rocking and sighing with . . . perhaps . . . the idea of a third child. It wasn’t to be. But the modernist house we fell in love with, well beyond our means? With three minutes to deliberate and a little extra work, we managed to swing that. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the consequences. One summer night, we rode the Vespa to a restaurant on the river, clad only in shorts, sandals, T-shirts, and, thankfully, our helmets. One sharp turn and we were down at forty-five miles per hour. I fell face first, road rash from my forehead to mangled big toe. He must have bounced off the chassis, shattering his ribs in eighteen places before landing unconscious on the easement. An operation removed the blood from his chest and lungs but introduced a dangerous hospital infection requiring IV antibiotics and months of recovery. It was nearly fatal.

Finally, as if to ironically underscore family togetherness, we passed risk-taking down to our children, along with the gene for alcoholism. The family that’s sober together stays together, and alive.

I’ve never seen Nina perform. I was too young during the fifties when she focused on old standards, and I was mostly oblivious during the sixties, when her work became overtly political. Or perhaps I should say I’ve seen her perform only on film. Either way, I believe she came into my life at the right moment, when I understood no love is without its shadows: brief periods of discord, longer stretches of mishaps and stumbling. (So sure I’d marry a blonde, but his hair was black.)

In the Compact Jazz recording, Nina sounds exhausted. Or (again) is she merely taking her time, the opening arpeggio savored as before a ten-course meal—that attenuated blaaaaaaack and mesmerizing colorrrrr, hairrrrrr? A flutter in her vowels, and hiss, a kind of shushing without the mean. I’ve tried to sing along but my voice sounds like skim milk. I rush the lyrics and interrupt her silences. I forget she sits on her chords till their vibrations fade. My melancholy is real, but no match for hers. She tilts her head to the side, not looking at anything, not the audience, not her manager hovering in the wings, not even her fingers on the piano keys. Oh please, she seems to say, just let me sing and get through the story of my true love’s hair, of my true love’s hair, of my true love’s hair.

To close, she resolves to a major key. It may be an attempt to oblige the audience, to lift the mood. All shall be well, she could be thinking, despite the time spent in a minor key. All manner of things shall be well.

Read more from Issue 15.2.