Factory Girl

10 Minutes Read Time

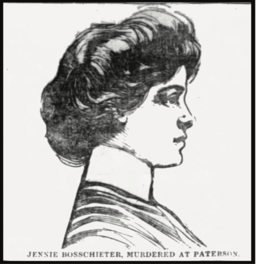

In the Silk City, seventeen-year-old Jennie Bosschieter makes ribbons inside a factory. Men work the vats of the neighboring dye houses, coloring so many miles of silk thread that they could connect Paterson, New Jersey, to the Netherlands, the country where Jennie was born, thousands of times and still leave enough to spare for the jacquard ribbon she watches over.

The first skein of American silk is produced here, in New Jersey. It takes only a few years until the mills in Paterson run against the length of the Passaic River, buildings for dyeing, weaving, machinery repair, and pattern storage pressing close along the banks, crowding out the light. They say you need good hands for this kind of labor, ones that know how to handle fabric with care, ones that know the feel of every silken thread.

A man on his way to work finds Jennie Bosschieter’s body down by the river the morning after she is murdered. She is a little more than a mile from her home. The night before, she had left her father and stepmother to go buy talcum powder at Kent’s drugstore and, though she didn’t return, they were not concerned. Perhaps, they reasoned, she spent the night at the home of Mrs. Klatte, a family friend who ran a confectionary shop.

The man finds Jennie in a place he thinks no woman should go. Here, River Road turns rough, and the grass is overgrown. Her head rests on a rock, and there is a small wound to the back of her neck. Otherwise, she looks undisturbed, except that she is missing her bloomers.

The Passaic River begins in Morris County, New Jersey. It is only eighty miles long but drops seventy-seven feet in one of the largest waterfalls in America at Paterson. This dizzying height is what Alexander Hamilton sees on a tour of the area, and he understands what others haven’t: the sheer force of the water as a potential for industrial development. In Paterson, Hamilton pushes for a series of raceways to be built as a way to harness this energy, power that will later be used to make cotton, continuous sheets of paper, the Colt revolver, and silk.

It is into the forceful tear of the Passaic that Jennie’s killers throw her bloomers after she is left on the roadside. The piece of white cotton swirling end to end until it is sucked into the polluted depths of the river. Jennie’s bloomers will never be found.

William Death and Andrew Campbell stand outside of Kent’s drugstore the night Jennie Bosschieter dies. Jennie and William Death once courted, but he married someone else five weeks ago. Imagine them there this late October evening, Jennie after a ten-hour shift at the factory, encountering Death on the street. He later says Jennie asks him that night why he didn’t marry her. “Because I didn’t think we thought enough of each other,” he says.

It is not Death but Andrew Campbell who convinces Jennie to walk with them down Main Street to Saal’s saloon over on the corner of River and Straight. Perhaps he wraps his arm through hers as they walk.

The saloon is well kept, a neighborhood favorite. The three order drinks quickly; they’ve all been here before. A short while later Walter McAllister and George Kerr join them in the backroom of the saloon, a small bottle tucked deep in McAllister’s pocket.

At the saloon, Jennie drinks one manhattan, one absinthe frappê, and two glasses of Great Western sparkling wine, one of which includes two to three drops of chloral hydrate poured from the bottle hidden in McAllister’s pocket and marked with only the drugstore’s name and the image of a skull and crossbones. When Jennie doesn’t falter under the drug’s effects, several drops more are placed in her drink. Then several drops more. And several drops more until Jennie is too weak to stand on her own.

Death, McAllister, Campbell, and Kerr all call chloral hydrate “knock-out drops,” the common phrase of the time. The mixture is first synthesized in 1832 through the chlorination of ethanol by a scientist from the German Empire working to discover how different compounds interact. The scientist can’t predict the ways in which his experiment will be used. In regulated amounts, chloral hydrate can be used as a sleep aid. In high enough doses, it can cause respiratory depression, the body struggling for enough oxygen.

In Chicago, Mickey Finn sneaks chloral hydrate into his patrons’ drinks so he can more readily rob them. Two years after Jennie’s death, Finn is arrested, and men will start saying they “slipped someone a Mickey,” as they place drops of chloral hydrate into women’s drinks.

Jennie is carried from the saloon to August Sculthorpe’s waiting victoria. Sculthorpe is a man who knows how to transport people quietly through the murky streets of Paterson in the back of his carriage. This night he does so for the four men and Jennie, whose head tips forward with every jolt until they reach an abandoned highway several miles from town.

Out there on Rock Road the four men throw down a blanket and then the heavy weight of Jennie’s body. They rape Jennie while Sculthorpe waits with his horse nearby. Later, the newspapers won’t say the word rape. They will say the men are alone with Jennie’s too-still form for thirty minutes out in a clearing in a dark New Jersey wood. One writer will dare to call it an orgy, as though Jennie were willing while the men took their turns.

The county coroner who examines Jennie’s body says that she died from trauma to her head. He tells officials that she was thrown to the ground while out for a walk with a man who meant her harm. The wound from the rock, he says, created a small bleed inside her brain. Jennie, he believes, could have been saved if she received medical attention in time. But out in the woods that night it’s a different story. After the men have raped her, they try to revive Jennie, shaking her roughly and rubbing her arms and face with their October-chilled hands. She only utters a small groan before she falls silent. There is, perhaps, some confusion before they rush her to a doctor, who asks why they’ve brought a dead girl to his home in the middle of the night. He sends the men on their way, Jennie’s body still inside Sculthorpe’s carriage. Jennie is dead long before her head hits the rock on River Road. She feels nothing as the men heave her down to the ground.

A few hours after she is found, the first headline about Jennie will appear in the papers. “Factory Girl Found Dead,” a New York Times piece will declare.

Jennie’s family announces that her funeral is postponed as a way to gather some privacy for her burial. Still, a crowd assembles outside her home until several thousand murmuring bodies follow the funeral procession to Fairlawn Cemetery, not far from where her body was found.

Jennie’s friends, other women from the silk mills, leave modest bouquets at her grave. A small mark of life deep in the winter.

Sculthorpe is the first to confess. He brings police to the exact place Jennie’s body was discovered and to a place close by where a pile of her hairpins lies in the grass. It is not long before Death, McAllister, Campbell, and Kerr are brought in and the newspapers report on their prestige and positions: the brother of a judge, an advertising solicitor, the son of a mill owner, and a bookkeeper at another mill.

Men in Paterson place bets on the outcome of the trial. They wager heavily on the likelihood that McAllister, Campbell, and Death will be convicted of second-degree murder. They bet Kerr will be convicted of a lesser charge, manslaughter, perhaps because he is almost twice the age of the other men, but more likely because of his family connections. No one seems to wager that any of the accused men will be convicted of first-degree murder.

On the day before the trial someone constructs a memorial on her grave, cardboard painted white, with the inscription “VENGEANCE IS MINE Saith the Lord” in red, along with a bouquet of white and red hyacinths.

On the fifth day of their trial, McAllister, Campbell, and Death are found guilty of second-degree murder. The jury deliberates for four hours, with five jurors holding out for a first-degree charge and one opting for acquittal. The men are sentenced to thirty years of hard labor.

Ten days later George Kerr pleads guilty to criminal assault. On the stand, Kerr says he arrived last to Saal’s saloon and that he barely knew Jennie at all. He says he would have come forward with his knowledge of Jennie’s death but that Sculthorpe reached the authorities before he could. For this confession, the judge says, he will be lenient, but everyone knows it is a favor to Kerr’s brother, the retired judge. For his part, Kerr receives a sentence of fifteen years.

Around Paterson, men begin collecting on their bets.

The guilty men are sent to Trenton State Prison, the oldest prison in New Jersey. Before they enter they ask to be taken to a saloon, where McAllister, Campbell, and Death down shots of whiskey. Kerr has a glass of warm milk. This is the last time the men will drink together, and on this afternoon there’s no chloral hydrate in McAllister’s pocket. No waiting victoria out on the street or darkened farm field along a deserted lane. No Jennie leaning against them, her breath stuttering in her chest.

In February, all the men except Kerr begin their labor assignments. Kerr will never work while inside the prison, which officials will claim is because of an ailment related to his eyes. McAllister and Death become factory men, making shirts inside the airless prison. Campbell works in a brush shop. Inside those penitentiary factories, the men’s hands grow used to the labor of shifting fabric, gears, machinery. Their hands learn industry, but the prison will never teach them what it means to hold silk thread between their fingers so lightly it won’t break.

In eleven years, Kerr will leave the prison at midnight during a cold February. Four years later, Andrew Campbell will do the same. Death and McAllister fade from the records.

In the Silk City, the Passaic River floods again and again as one by one the mills go quiet. There, in the city known for its ribbons, the people forget the way the factories smelled early in the morning or how to place a jacquard pattern into a machine. And, long before the mill buildings crumble, they’ll forget Jennie Bosscheiter’s name and the way her body knew how to move to the sound of the silk looms.

Read more from Issue 15.1.