YouTube Comment 2 to Video of I Like America and America Likes Me by Joseph Beuys

27 Minutes Read Time

I had hoped that I could make art after having a baby but now understand the temporary impossibility of this goal. My eight-month-old son Mauricio lies before me in his crib, finally sleeping following the “fade” method, a questionable aid. The scent of milk perfumes my life. My mind fills with visions of his infinitesimal hands and his furious Nixonian face. I am in love with my son. I love him. I don’t think it’s very good for my work. My work might be dead. As I stand over Mauricio’s bassinet and breathe him into me (I am thumb-typing this Comment on my phone), I can feel my formerly stringent aesthetic standards crumble. I used to spend my days worrying about Wittgenstein and curatorial ethics and art-world economics and faux-art institutional point-of-viewlessness. Today I entertain mostly globular thoughts, framed by threadbare conceits like don’t die, exhaustion, and love.

I am a performance artist, or I was. Right now I am a single mother. A single mother does not make art by loving in a frenzy, cleaning up shit, and going to work. Does she? A single mother does not make art by freaking out about childcare and sore breasts and pumping breasts and cracked nipples. A single mother does not make art by surviving the wail-struck darkness. Right? Instead, she walks into her office with the haircut she hacked out herself and sits down to write memos on how to expand Snapchat’s—that is, her employer’s—March $1.8 billion Series F financing round with an even more lucrative $200 Series FP round involving Alibaba and WeChat. She does this only so that her son will have food, shelter, medical care, a nanny, and savings that will probably vanish into one of Los Angeles’s better private schools. The single mother does this. This is not art. It doesn’t feel anything like art. And because the single mother does not make art by raising her infant son, her actions are merely that: actions, not “Actions.” Her output remains unreviewed, ungranted, unworkshopped, and undocumented, except for when she records it online in the form of Instagrams or Facebook status updates or Reddit posts or rejected Wikipedia entries or furious, unread Comments on YouTube videos.

A long time ago, I ran naked through the streets of Tokyo while singing Gary Glitter songs to protest war capitalism by dematerializing the art object. Once I undertook an anti-death-penalty art performance/hunger strike in Atlanta that included sending SOSs in Morse code with a Maglite. I painted bad text paintings. I made a film about clowns that premiered at Slamdance. I spent a summer at Yaddo choreographing all of my dreams. A year ago I busied myself with unrealized plans to produce a show featuring myself as an emotionally vulnerable alt-right insurrectionist named Texit. I went so far as to purchase a fake Colt 9mm submachine gun from eBay and to stitch a blue costume with a red cape and “Texit” spelled out on the chest in sequins.

Now the fake 9mm submachine gun and Texit costume languish at the bottom of my closet and I labor at a “norm” job. I materialize my love for my son through intermedial gestures that combine spoken word with breastfeeding, breast pumping, doctor visits, kissing, worrying, and unsleeping.

Some would say that my laborious devotion qualifies as art. In 1917, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven tried to teach us that the artist can transform base existence into an art product when she declared that urinals belonged in art galleries, an affront for which Marcel Duchamp later received credit. In 1979 the Croatian artist Sanja Iveković masturbated as performance art, calling her piece Triangle in honor of her vagina and the ergonomics of state surveillance. The contemporary conceptualist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who argues that cleaning is art and that landfills are social sculptures, grew famous for vacuum-cleaning artistically and also shaking the hand of every sanitation worker in New York. A feminist performance artist named Jill Miller drives around Pittsburgh under a giant pink fiberglass breast in a “Milk Truck,” wherein she provides safe harbor for new mothers who text her when they get kicked out of restaurants for trying to breastfeed. In 2016 Guggenheim fellow and autoethnographic artist Simone Leigh occupied New York’s New Museum’s top floor with a minority-centered alternative medical space called a “Waiting Room” that had “care sessions,” including acupuncture workshops and guided meditation classes. And in 2011’s The Birth of Baby X, performance artist Marni Kotak actually gave birth to her son in Brooklyn’s Microscope Gallery, which earned her a 2012–2013 Franklin Furnace Fund award. In the minds of these very resourceful women, the art and caring fuse into one thing.

But taking care of and loving my son does not feel like performance art to me.

Art requires a distance, an artifice, an audience, a purpose apart. My critique concerns more than capitalism. Even if the artist gifts her work to a sacred space untroubled by money markets, she creates an energy for an audience. Creating an energy for an audience requires her to see herself with the eyes of others and mandates that she package the work for those others’ consumption.

But I do not want to create a consumable out of my adoration of my son. My love exists for him alone.

My art must come in other forms.

But I am too tired to make anything.

In 1974 the god who was the German performance artist Joseph Beuys decided that he would cure America with an action designed to balm the wounds caused by the frontiersman’s genocide of the American Indian. Beuys planned on achieving this miracle by flying to New York and living in a cell with a coyote for one week. Beuys and his assistants would provide food, shelter, companionship, a place to urinate and defecate, and spiritual counsel to the coyote. The coyote represented American Indians, and the Wall Street Journals that Beuys’s assistants brought in every day for the coyote to pee on represented the United States and its capitalism.

Beuys called the performance I Like America and America Likes Me, though it’s often known as Coyote.

Using a peeing coyote as a stand-in for murdered Native Americans proved one of Beuys’s most impudent ideas, not in the least because he had joined the Hitler Youth in 1936, volunteered for the Luftwaffe in 1941, and fought either so ferociously or ineptly on the western front that he was wounded five times. Beuys also battled in the Crimea, acting as a rear gunner on a Stuka dive bomber that got shot down over the Peninsula. When Beuys later began making artwork, one of his most memorable productions entailed his telling falsehoods about the rescue party who salvaged him from the Stuka wreckage. Beuys said that after he plummeted to the earth, his broken and burned body found salvation in a tribe of Tatars, who covered his skin in milk and animal fats and then wrapped him in layers of felt. “Had it not been for the Tartars [arch.], I would not be alive today,” he told an interviewer in 1978, explaining why many of his works contained the elements of felt and tallow, and why he himself often donned a felt suit. But the Tatar story proved a complete fiction, as rescue-party Germans reported discovering Beuys alone in the snow, without a nomad in sight. Also, Stalin had begun cleansing the Crimea of the Tatar tribes, so they would not have been in the area at that time.

Why did this fantasist and Hitler lackey think he could rehabilitate America and its Native victims? Beuys possessed a fanatical trust in himself, a self-regard that all great artists, it seems, must cling to—if not to create objectively great work, then at least in order to persuade history-blind gallery owners to give them white cubes for coyotes to pee in, and to enlist teams of assistants to help the artists pull off their performances.

On May 21, 1974, Beuys arrived in New York on a flight from West Germany. He spent his journey wrapped head to toe in a felt cloak and with his eyes shut so that he would not see any part of America until he reached the art space. An assistant helped him carry several items: a crooked staff, two large pieces of felt, a pair of gloves, a mystical diagram, and a musical triangle with its metal beater. A white ambulance transported Beuys from the John F. Kennedy International Airport to impresario René Block’s gallery on 409 West Broadway, in Soho, where the coyote, captured from the wild by yet another stalwart assistant, waited for him in a wire-netted pen set up in the building.

Beuys did not think that his art consisted of taking care of the coyote. He did not lay down the Wall Street Journal in the same spirit that Simone Leigh orchestrated an acupuncture class on the top floor of the New Museum. Beuys did not clean up the coyote’s poop thinking that he embodied conceptualism like Mierle Laderman Ukeles. When he brought the coyote into the gallery from the wild he did not say Voila! like Marni Kotak did when she brought her own son into the Microscope Gallery from the wild space of her womb. Beuys did not say “my life and my art are one.” He had something fancier in mind, like the embellishments he told about the Tatars.

Beuys entered the René Block Gallery bundled up in one of his felt blankets with the crooked staff poking up above his covered head. In a corner sat a pallet of straw that both Beuys and the coyote would sleep on, and strewn around lay bundles of the Wall Street Journal. Assistants placed in the pen one dog bowl full of meat and another of water. The second piece of felt, lumped on the floor, offered an additional place to rest or sleep. The gallery featured two large rectangular windows from which light cascaded into the shadowy room.

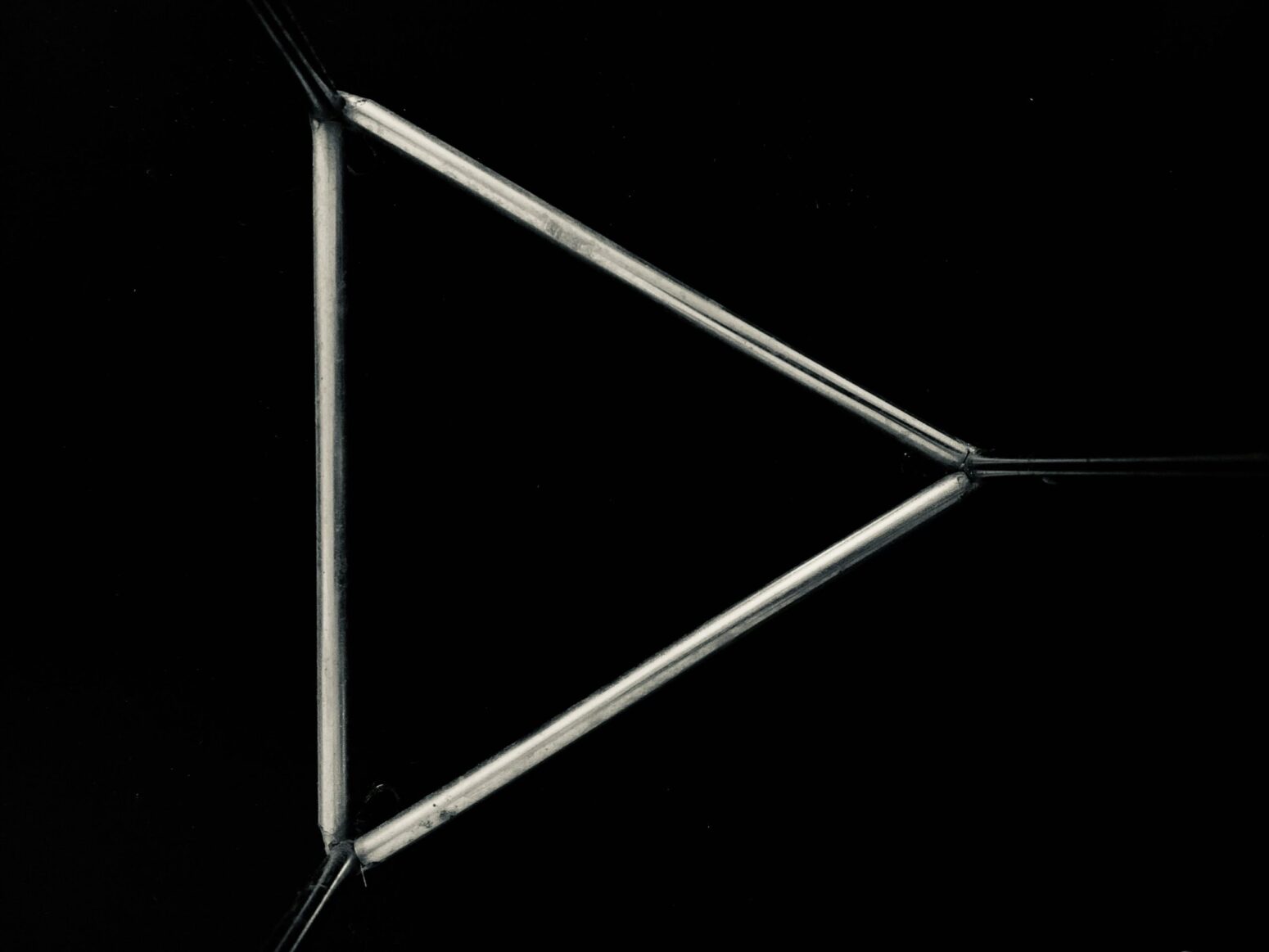

As the reader can see from the YouTube video this Comment addresses, one of Beuys’s minions filmed the Beuys-coyote encounter. The tape shows the poor canine skittering nervously as Beuys first appears to him on day one. Beuys enters the space moving smoothly like an apparition, his body encased in the thick felt poncho, and with a “head” made out of the crooked staff. He begins bowing and squatting in front of the coyote in an incomprehensible ritual dance. The coyote stares at him, and Beuys seems to stare back—apparently from an opening in the felt. The coyote prances around with anxiety as Beuys continues to bow and squat rhythmically and walk around like an alien priest. Beuys occasionally holds up a diagram with a triangle and lightning bolts that illustrates the New Agey and racist musings of fin de siècle Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, who thought that Culture, Economy, and the State together could combine into a perfect “threefold social organism.” Beuys believed he would spiritually mend the American Indians/coyote and the murderous Americans with his dancing and his mystical Steiner drawing. Sometimes in the video he takes out his metal triangle and rings it with the beater. Ding, ding ding, it goes. Ding, ding, ding.

The coyote keeps jumping around for the first two, then three days. But after that, it grows curious about its new prison mate. It walks up to Beuys and pulls on his felt cloak with its teeth. The coyote then runs to its food bowl and kicks it around, looking back to see if Beuys is observing its antics. Beuys continues bowing and banging on the triangle while wrapped up in the felt with the crooked-staff head. The coyote eventually relaxes and rests at Beuys’s feet, occasionally leaping on him and tugging on the cloak some more.

I first saw Coyote in 2005, when I was attending RISD for an MFA in design and media. At the time I thought that I “got it.” I admired how Beuys released the shamanistic powers of the performance artist, who could direct energy through embodied practices that would exorcise the old blood-stained ghosts of power, history, hierarchy, and gender. I knew, tangentially, that Beuys married (Eva Wurmbach) and even had two children (Wenzel and Jessyka), but these facts seemed peripheral to me. I saw Beuys as a singular creature who used the triangle in his art to capture ancient chthonic forces that would set his audience on a path toward liberation and aesthetic transcendence. In works such as Coyote, I believed that Beuys created a new secular religion and invented a fresh mode of living.

That is to say, I had no idea what Coyote was about. But as it turned out, neither did Joseph Beuys.

Mauricio’s father is Brandon Chu, who pays me $1,940 a month in child support. Since I pay my childcare worker, Fred Hernandez, a Los Angeles living wage, I am out-of-pocket $2,820 monthly on that score alone. I possess sole custody, since both Brandon and I wanted it that way. Brandon sees Mauricio four times a month, but he has a new girlfriend now, Seraphina, and they plan to get married and create their own family. I am good with this.

I never wanted to be pregnant or have children until I did become pregnant and have a child. Now I apparently resemble many other women in my desire to be a mother always, a passion that eclipses anything else. Except that I also want to make art more than anything else too.

Mauricio is mine and separates me from art. As of this morning, he weighs nineteen pounds and three ounces. Copious, very soft black hair radiates from his delicate egg head, and he inherited his father’s eyes and my dark skin. He looks at me with a vast emotional intelligence that reveals itself in the furrow of his forehead and his careful watching—like a judgmental druid—as I move about our house, cooking him vegetable mash and cleaning up vomit and pasty food bits. He observes me with the affected neurasthenia of James Baldwin as I try to slither away from his nursery in order to get him to sleep. At the end of the day, he stares balefully at his nanny Fred, the charitable Dominican American nursing assistant from Glendora, before bursting into tears. Both Fred and I agree that Mauricio has developed certain sophisticated judgments about the arrangements of society that he will share with us when he can finally speak.

The most perfect arrangement would be that neither you nor Fred ever leave my side, I suspect that he will say. I find it tragic when either of you goes away.

Again, this is not art. I am worried that my art has drifted away from me so far that I can only see it as a small point on a cosmic graph, an infinitesimally tiny dot glimmering in opposition to two large points that cluster close together.

Like Beuys’s art in I Like America and America Likes Me, my life can be described in terms of a triangle.

Euclid first explained triangles in mid-third century BCE. He taught us that an isosceles triangle displays two sides of equivalent length and bears congruent base angles. Euclid called his proposition pons asinorum, or the “bridge of donkeys,” to convey his distaste for people who couldn’t understand it.

A line, on the other hand, does not boast an angle. It consists of only two points. Euclid defined a line as “length without breadth,” and Plato described lines as “extremities of a surface.” In the early twentieth century, the Encyclopaedia Britannica said a line was the “path of a moving point.”

Much of the time I worry that I am a line. On those depleted days, I cannot discern art on my graph at all. It seems as if the extremity of my surface extends only between Mauricio and me. I exist as pure length without breadth. I walk on a path that moves exclusively toward him.

X X

Mauricio Me

But that’s not really true. I am an artist, and that means art remains here, somewhere. I will admit, though, that my muse retreated from me awhile ago. The blame for my artistic block cannot rest with Mauricio alone. My clown movie screened eight years ago, and I streaked through Tokyo the week that Barack Obama first debated Mitt Romney. For the past twenty-eight months, economic disorganization, job changes, emotional kaputness, and a series of failed romantic relationships have rendered me incapable of doing much beyond working at my norm job and writing strange Comments like these on the internet. My baby provides only the most satisfying of several distractions that long ago suspended my full artistic practice.

Still, the art cannot be gone. It must somehow remain with me.

As such, I cannot be a line. I am a triangle, like the metal triangle that Joseph Beuys banged at the coyote in 1974.

Recall the isosceles triangle and its two equivalent lengths and congruent angles. That is the pons asinorum I walk daily. Mauricio and I stand in very close, equidistant proximity, while art marks a spot millions of miles away. As such, the two sides of the triangle match and the base angles mirror one another:

X

Me

X

X Art

Mauricio

Joseph Beuys thought that Coyote also organized around the form of an isosceles triangle. When he finished his performance, he grandly told an interviewer: “I believe I made contact with the psychological trauma point of the United States’s energy constellation; the whole American trauma with the Indian, the Red Man . . . You could say that reckoning has to be made with the coyote, and only then can the trauma be lifted.”

Beuys believed, wrongly, that three points defined I Like America and America Likes Me. According to Beuys’s mistaken mathematics, the coyote constituted the first point, which designated national trauma. Art formed the second point. The third point existed as Beuys himself, the “I.” Beuys felt very close to art but did not imagine that he, as a caregiver, existed as art, the way that Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Jill Miller, Simone Leigh, and Marni Kotak made their cleaning, safehousing, medical healing, and birthwork art. Beuys worked as a showman and had to add a separate element, a contrivance, like that created by the artificial Tatar story. I think his laughable messiah complex might explain his insistence on decoupaging coyote care with arty stuff: Saviors are heroic and so have to “do something.” Something, that is, besides nurturing their own families and communities or safeguarding breastfeeding moms or playing with rapidly domesticating animals.

Joseph Beuys’s spiritually vaudevillian streak explains why he put on the cloak, made a head out of a crooked staff, and danced weirdly. It also confirms that he believed art formed one point and his “I” formed another. The coyote manifested its point at a farther remove, since it represented The Wild and also The Red Man, according to Joseph Beuys.

Beuys thus thought that he created in I Like America and America Likes Me a perfect isosceles triangle:

X

Beuys

X

X Coyote

Art

I thought the same thing for a long time too.

But I now know that Beuys and I both made an interpretive error. Beuys did not make contact with the Red Man or force a reckoning with American genocidal trauma by flapping a Steiner diagram in front of a coyote or beating on a metal triangle. These hoped-for residues of Coyote do not exist. The inventor of the Tatar fiction could not heal American genocidal memory through the racist act of metamorphosing Native Americans into coyotes. This is why the felt cloak was nothing. The crooked staff that stuck out of it like a head was nothing. The Wall Street Journals were nothing, except good for pee soakage. The Rudolf Steiner diagram was nothing. The music made by the beating of the triangle was nothing. All of these elements may be withheld from Coyote and fed instead to Euclid’s donkey.

I Like America and America Likes Me is actually something, though. It succeeds as art, but not as the art that Beuys intended. Coyote’s art exists in Beuys’s caring for another creature. No meaning prevails in the work apart from Beuys’s being with the coyote. He made the leap that I refuse to take with Mauricio, but that others after him, such as those feminist performance artists, accomplished with much greater audacity.

In Coyote, Beuys merged with his art because his art enacted love. He achieved this merely by tending to an animal, as does a zookeeper or a pet parent or a dogsitter.

X X

Beuys/Art Coyote

Disguised in his felt cloak and crooked-staff head, Joseph Beuys stands in René Block’s gallery with the coyote and bows to the beast like an ersatz medicine man. The coyote looks at him for a while and then walks over to one of the gallery’s rectangular windows with its view of the street outside. Beuys continues to genuflect and crouch. The coyote grows bored of staring out of the window and runs back to Beuys and bites playfully at the felt cloak. Beuys bobs around some more. The coyote wags its tail and jumps on him. Then the coyote runs behind Beuys and snaps at his bottom, so Beuys stops dancing. He turns around to look at the coyote, unsure what to do.

Recall that Joseph Beuys brought with him a pair of gloves. As this YouTube video reveals, on day four or five, Beuys stops bowing and crouching and starts just throwing the gloves at the coyote like he would a tennis ball. Fetch! The coyote chases after the gloves, wagging its tail. Beuys throws them again. Then the coyote jumps on him and pulls at his cloak some more so that the game can continue. Beuys patiently obliges the coyote, who perhaps did not like to be imprisoned in René Block’s art gallery but did like Joseph Beuys.

That is why Joseph Beuys called his action I Like America and America Likes Me.

Fred Hernandez, Mauricio’s nanny, sometimes stands next to me as I look down at Mauricio sleeping in his crib. He’ll typically do this if I start crying.

“You’re a good mother,” Fred will say.

“No, I’m not,” I’ll answer.

Fred comes from a family of eight brothers and sisters. He trained as a nurse’s aide at West Los Angeles College, which maintains a very fine program. Fred worked in USC’s pediatric-oncology ward for twelve years but then burned out, and now works for me. He stands five feet seven inches and is forty-one years old. Fred’s fur-brown eyes glisten with specks of leaf green. He cracked a molar that he needs to get fixed. Fred knows how to deal with diaper rash and reverse cycling and even problems with let-down. He understands how to reassure worn-out women.

I’ll hold Mauricio in my arms and close my eyes and cry for a while until I feel better. He resembles primordial life, breathing and wriggling. I attend to Mauricio’s perfect skin with a combination of coconut butter, shea butter, and cornstarch. I pump my breasts at my Snapchat work desk, and Fred feeds Mauricio my milk the morning after. I don’t sleep very much at night.

“You’re a good mother, Amanda,” he’ll say again. “You’re catching on just fine.”

“Thank you, Fred,” I’ll say.

It doesn’t really get a lot more interesting than that at my house these days, unless you count the minute movements that I track in Mauricio’s face when he looks at me or when he naps. The other okay moments come when I write these Comments on YouTube videos or in Reddit feeds or Facebook posts or when I post on Instagram or send my friends emails.

When Joseph Beuys made I Like America and America Likes Me, he was a line but erroneously believed that he was a triangle.

Joseph Beuys unintentionally invented what I call care art, that is, art that takes the form of caring for another being or, perhaps, yourself. When Sanja Iveković masturbated as art, she took care of herself. When Mierle Laderman Ukeles artistically vacuumed, she took care of herself and her family. When Jill Miller performatively dashes around Pittsburgh providing a breastfeeding space, she takes care of ill-treated moms. When Simone Leigh created a Guggenheim-y alternative medical-care establishment out of the top floor of the New Museum, she offered the community healing. And when Marni Kotak gave birth to her son in the Microscope Gallery, she enacted the ultimate care of nourishing a baby within the body and then pushing it out into the scary world.

These women took up Beuys’s challenge and achieved what he could not. They did not need to dress up in felt or wave around a manifesto. They embodied Euclid’s breadthless line and manufactured work that proved indistinguishable from their own laborious acts of goodwill. Very little artifice exists in the space between these artists and their art. They added nothing superfluous to their creation of art through care.

X X

Giving a damn Art

As I write this (it has taken me three days to get this down, and I’m now working at the desk in my bedroom), Mauricio cries out from the nursery. My entire body stiffens with something like pain, but Fred has told me that I need to start consistently sleep training my son. Sleep training may take three different forms: (1) the “cry it out” method, where the baby wails itself to sleep; (2) the “no tears” method, where the parent staggers into the nursery every time the baby cries; and (3) the “fade” method, where the parent sits on the floor with the baby shrieking in his crib and then silently crawls away when the kid finally drops off.

“Cry it out,” Fred always says, raising his eyebrows at me.

At this moment I sit in front of my computer and weep as my son cries. I look at the closet where my artificial gun and blue-and-red Texit costume lie buried beneath some coats and books and whatever else I squashed in there.

I could take the fake 9mm Colt that I intended to use in Texit, commandeer the Gagosian, place Mauricio’s bassinet in the center of the gallery, and then “fade”/crawl around the bassinet and call it art. Or I could let Mauricio cry unrelievedly in the bassinet and call it art. Or I could run over to the bassinet every time he cries and call it art. I could sit at the base of the bassinet and cry and call it art, and when my boss calls me repeatedly on my iPhone, I could hold up the phone for the audience and bawl over said boss’s ringtone, which is an excerpt from Yoko Ono’s 1973 anthem, “Angry Young Woman.”

But I am not a line; I am an isosceles triangle, like Joseph Beuys thought he was. I am possessive of my son and also a fancy egomaniac like Joseph Beuys, so I need to “add something.” What I am really trying to convey in this perfervid Comment about Joseph Beuys and his coyote is this: I remain an artist in search of a style, in search of inspiration, in search of an off-ramp to this donkey bridge across which I trudge and amble. My only “creative time” comes when I write these interminable Comments and post and spellcheck them and noodle with the syntax and then check to see if I get any hearts or likes or shares.

Still, writing is not my art, because I am a performance artist with a social practice that I built over the last twenty years. I do not want to be a writer because writers trade color, sound, speech, the stage, the street, and thus the feel and touch of other human beings for this haunted craft of word design.

On YouTube, the coyote wags and nips, while Joseph Beuys, the husband and father, basks in the delightful illusion that felt blankets and lunatic dancing make him an art shaman who can heal the world. His galactic self-confidence and apparently robust circadian rhythms made everything easy.

But I am struggling.

Read more from Issue 14.2.